Wandsworth Town

Conservation Area Appraisal No.19

Contents

- Part One: Introduction

- Part Two: Conservation Area Appraisal

- Part Three: Management Strategy

- Locally Listed Buildings

Part one: Introduction

Outline of Purpose

The principal aims of Conservation Area Appraisals are to:

- Describe the historic and architectural character and appearance of the area which will assist applicants in making successful planning applications and decision makers in assessing planning applications;

- Raise public interest and awareness of the special character of their area;

- Identify the positive features which should be conserved, as well as negative features which indicate scope for future enhancements.

It is important to note that no Appraisal can be completely comprehensive, and the omission of a particular building, feature, or open space, should not be taken to imply that it is of no interest.

This document has been produced using the guidance set out by Historic England in the 2019 publication Understanding Place: Conservation Area Designation, Appraisal and Management, Historic England Advice Note 1 (Second Edition).

This document will be a material consideration when assessing planning applications and as an evidence base for the Local Plan.

What is a Conservation Area?

The statutory definition of a conservation area is an ‘area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’. The power to designate conservation areas is given to local authorities through the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservations Areas) Act, 1990 (Sections 69 to 78).

Once designated, proposals within a conservation area become subject to the national policies outlined in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), the adopted London Plan policies, and the conservation policies set out in the Council’s Local Plan.). Our overarching duty, set out in the Act, is to preserve and/or enhance the historic or architectural character or appearance of the conservation area.

Public Consultation

Public consultation on the draft Appraisal was carried out between the 10th February and 24th March 2023.

This document was approved by the Planning and Transportation Overview and Scrutiny Committee on 4th July 2023 and the Executive on 19th July 2023.

Designation and Adoption Dates

Wandsworth Town Conservation Area was designated in September 1984 and extended in May 1989.

This Appraisal was adopted on the 31st of August 2023.

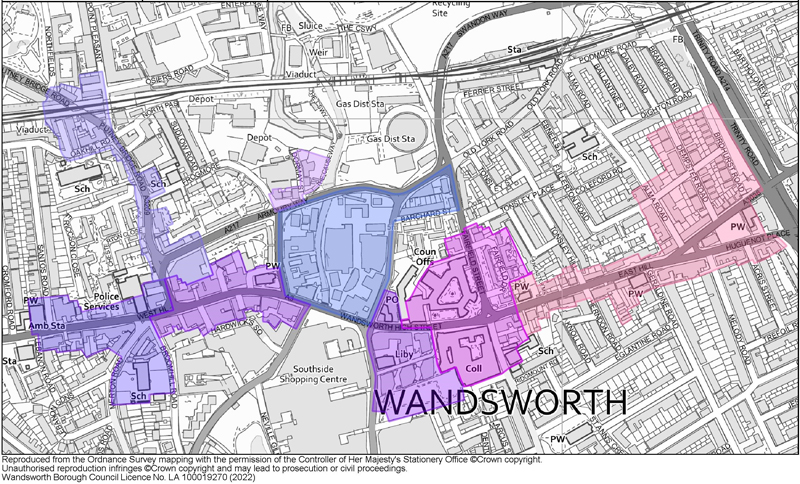

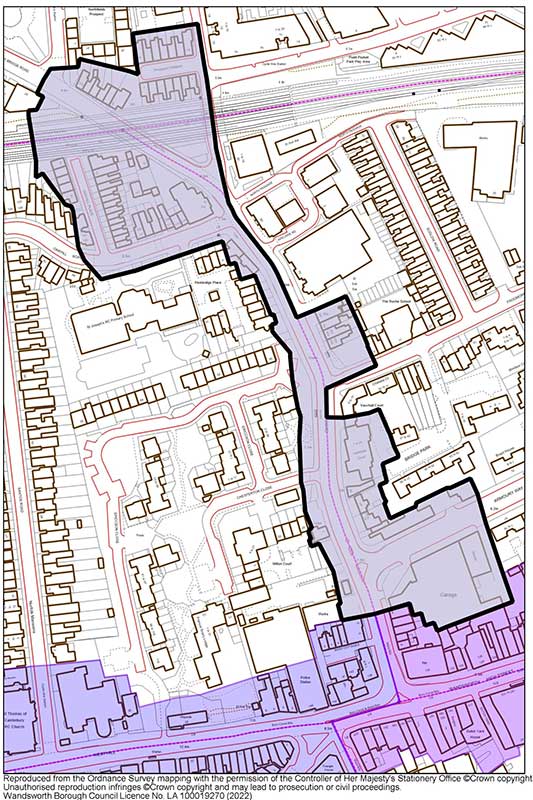

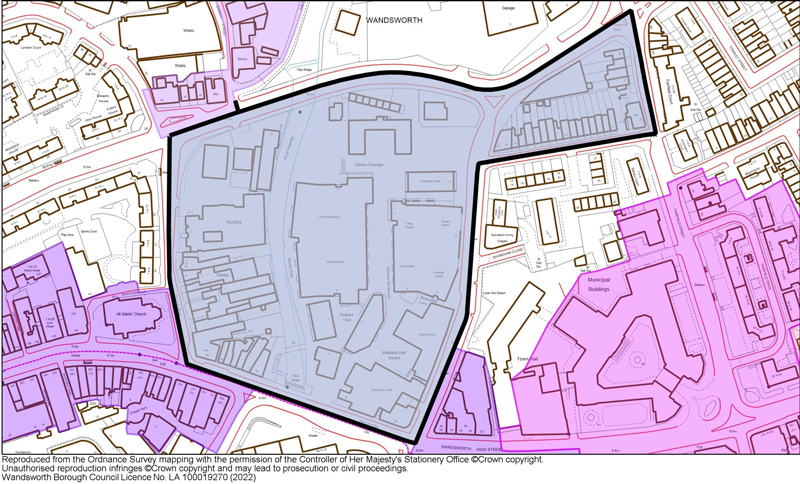

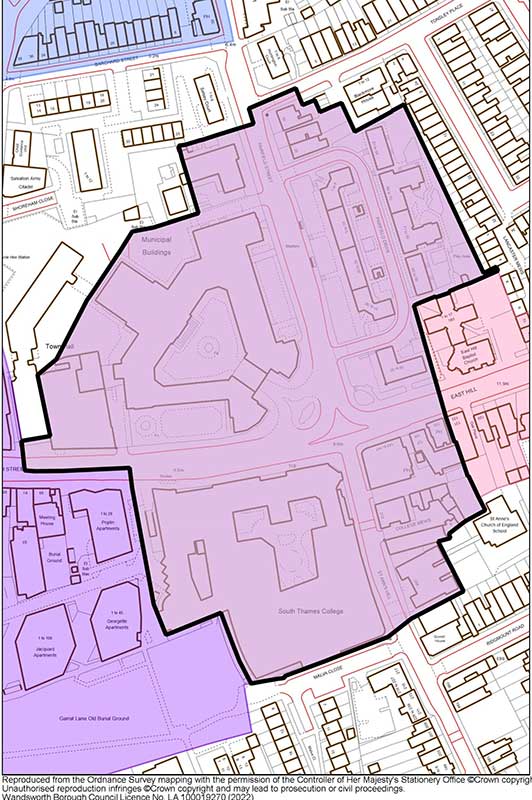

Map of Conservation Area

Summary of Special Interest

The special character of Wandsworth Town Conservation Area is derived from it being one of the oldest and most important settlements in the borough. Evidence of its historic development and street pattern remains and this, together with an attractive townscape and its wealth of listed buildings, means that it is an area which is of both historic and architectural importance.

Formerly one of the principal industrial centres, Wandsworth attracted non-conformist communities, and remnants of its manufacturing past and the influence of its habitants are still legible, notably the close association of places of work, living, and worship. The strong and steadfast brewing industry is particularly evident in the number of surviving public houses, as well as modest worker’s style cottages, which contrast with wealthier merchant owned villas on the fringes of the Conservation Area.

Historic Development

Fig. 3: Wandsworth village as depicted on Peter Gardner’s 1640 map of Allfarthing Manor (based on a survey of 1633). North is to the left. (SHC:3991/1: Reproduced by permission of Surrey History Centre; copyright of Surrey History Centre

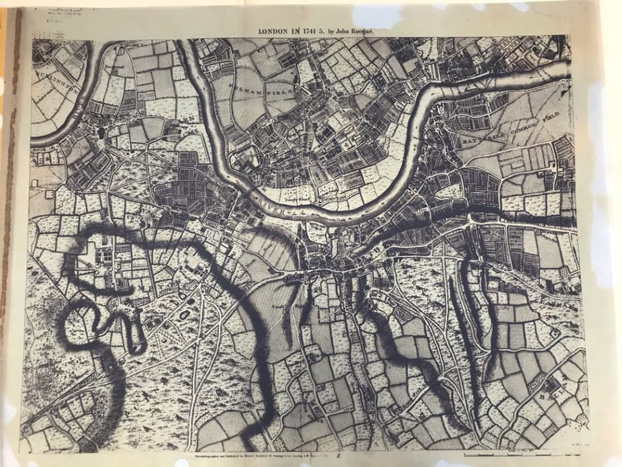

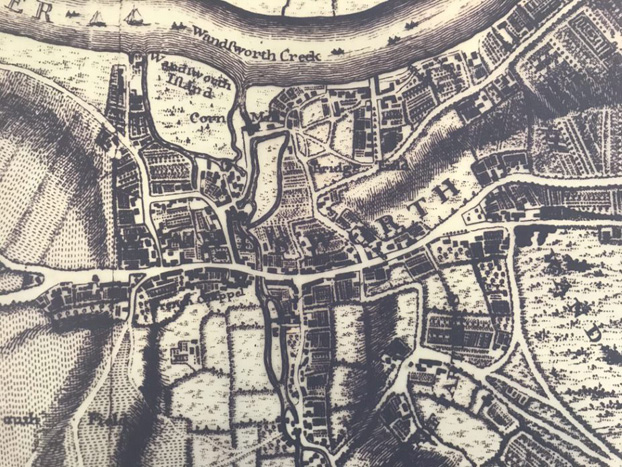

Fig, 4: John Rocque London in 1741-1745

Fig. 5: John Corris’s Map 1787

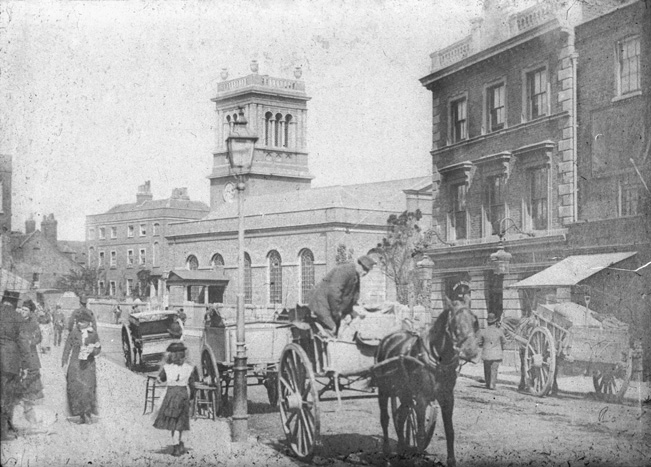

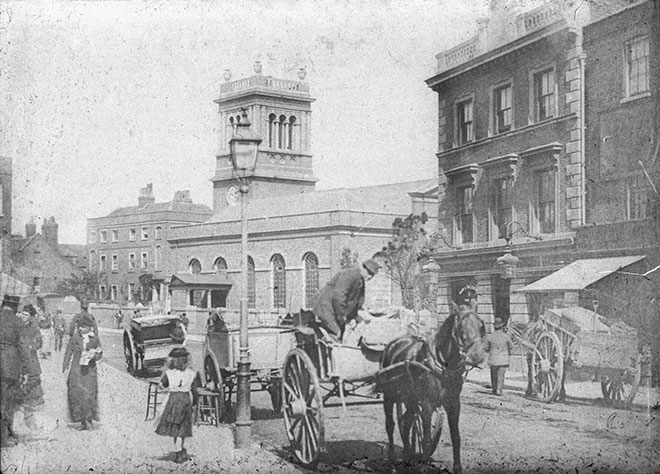

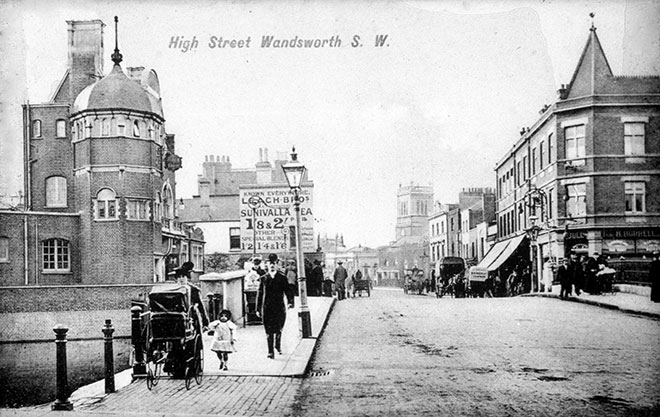

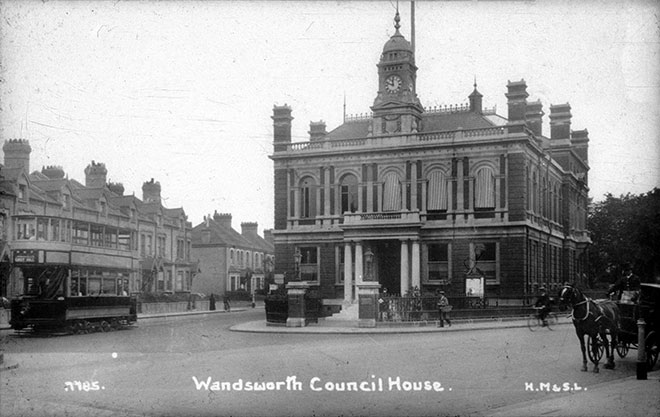

Fig. 6: View west from Putney Bridge Road, 1900. Source: Wandsworth Heritage Service

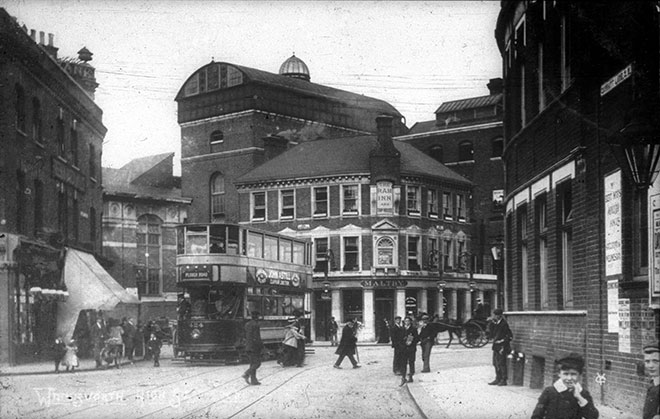

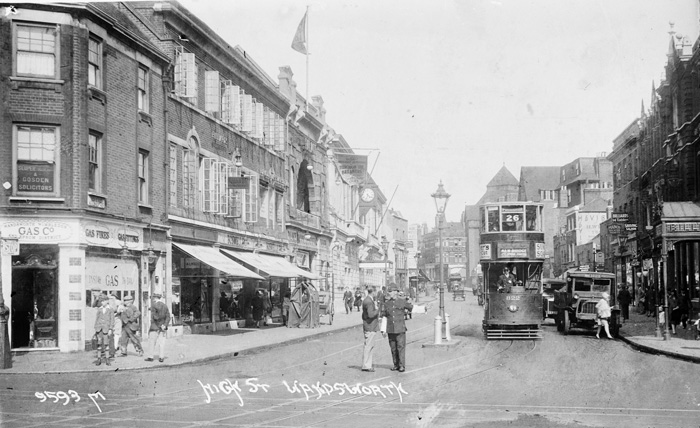

Fig. 7: High Street looking eastward, c.1910. Source: Wandsworth Heritage Service

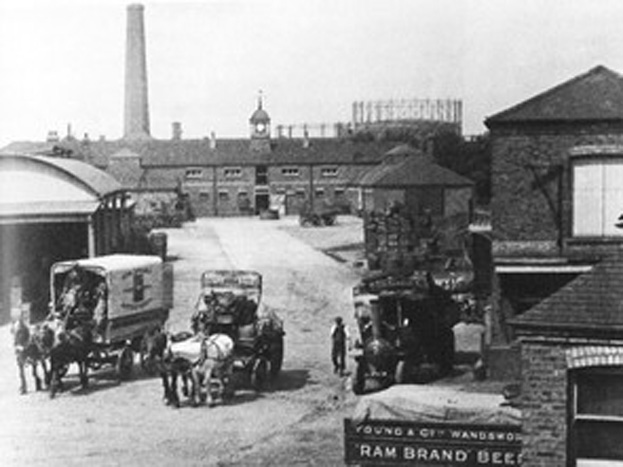

Fig. 8: Ram Brewery, looking north from Garratt Lane, c.1910. Source: Wandsworth Heritage Service

Fig. 9: Huguenot Place c1921(looking toward Melody Road). Source: Wandsworth Heritage Service

Fig. 10: High Street c.1925 looking east from Garratt Lane & Ram Streets. Source: Wandsworth Heritage Service

Fig. 11: Aerial view of Wandsworth Town in June 1937. The construction of Armoury Way is visible. Source: Britain From Above.

Fig. 12: View from inside the Ram Brewery toward the stables. Date unknown.

Fig. 13: Town Hall looking West showing original extent before demolition of west bays, 1952. Source: Wandsworth Heritage Service

The parish of Wandsworth has its foundations divided into four manors: Wandsworth, Allfarthing, Down, and Dunsford, and the focus of the settlement was aligned with the lowest crossing of the river Wandle. This position served the east-west route from Richmond and Kingston into Westminster via Thames crossings at Vauxhall and Lambeth. The amalgamation of a popular trade route, the clean, fast-flowing source of fresh water offered by the Wandle, and its confluence with the Thames, attracted a rich mixture of commerce and industry from an early date.

Since the Middle Ages the town has been one of the principal industrial centres around London, based on the power generating capacity and water quality of the Wandle. Huguenot émigrés were attracted in the 17th and 18th centuries, and by the 19th century, industries included drug grinding, snuff milling, silk printing, felt making and the world's largest calico bleaching works.

Patterns of early settlement remain legible in the subsequent urban growth of Wandsworth, with the dense core of the medieval village with its narrow and deep plots occupying the base of the Wandle valley, contrasting with the more generous, semi-rural plots surrounding, as well as along key routes. In the mid-19th century, country lanes and footpaths were enlarged and straightened into roads and side streets. The narrowness of these roads, and irregularities in their course and alignment suggests early and semi-rural origins.

Central to the Conservation Area, the High Street is the main thoroughfare and today forms part of London’s south circular route (the A3). The gently curved road offers shifting views as one travels along it, with All Saints’ parish church strategically located at the central bend, and a second subtle change of course occurring further east at the bridging point of the Wandle. This important curve persists despite a road widening scheme in c.1913, which saw the demolition of many earlier buildings along the southern side. The busy road contrasts with the historic narrow lanes which branch off the High Street, leading to informal backland plots.

It was common for early roads to widen at major junctions, and this probably explains the triangular open space at the intersection of Wandsworth Plain, Frogmore, and the Causeway, although the insertion of Armoury Way in the 1930’s has eroded the legibility of this relationship. The Armoury Way bypass, completed in 1938, has had a negative effect on the southern part of the sub-area, both in the destruction of buildings in its path and through the visual and noise impact of high levels of traffic. The new commercial buildings it has attracted have mostly been motor-related.

From the late-medieval period to the 18th century, the character of central Wandsworth was that of a dense and varied settlement, with a patchwork of vernacular buildings which were frequently altered, extended, or replaced. Many earlier buildings would have been timber-framed and weatherboarded, construction which was gradually rebuilt or encased in brick as more robust building materials became increasingly accessible.

Timber-framed buildings survived into the early 20th century, but even after extensive rebuilding, the dense, mixed, informal character of the former village can still be appreciated along stretches of the High Street, such as at Nos. 110-124 (even) (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14: Nos. 110-124 Wandsworth High Street

For the greater part of the 18th century, brick was something of a status symbol for the most affluent inhabitants, many of whom chose to live on the West and East Hills overlooking the village. A survival of the ‘compact and well-built’ urban vernacular survives at Nos 140 and 142 High Street, a pair of double-fronted houses. Slightly further up the social scale was the distinctly urban form of Church Row, townhouses of wealthy parishioners within view of their place of worship.

On the elevated land overlooking the village were scattered a number of country seats of the London gentry, but in the early 19th century, with the intensification of commerce and industry, these upper- and middle-class part-time residents were slowly repelled, and the social prestige of the place rapidly declined. As the price of houses and land fell, charitable and religious institutions were able to establish themselves, with several grand houses converted to schools (such as 12-16 Lancaster Mews) or overtaken by terraced housing which accommodated artisans and a burgeoning and youthful lower-middle class.

The town centre is still dominated by the now redeveloped Ram Brewery complex, and there is an extensive industrial hinterland to the immediate north and south of the area also undergoing development, which will change the character of the area and its setting. The town was centred on the ecclesiastical focus of All Saints Church in the High Street. Largely because of its manufacturing history, there was also relatively early development of non-conformist communities. This strong tradition is still visible in the central area, with the oldest chapel site in Chapel Yard (16th Century, rebuilt 19th Century), the Quaker Meeting House (18th Century), and with Baptist (demolished 1995), Methodist, and United Reformed Churches on East Hill. Catholics were represented on the edge of town in Putney Bridge Road and at either end of East and West Hills.

The connection between manufacturing and non-conformity was associated with a desire to live, work, and worship close together. As a result, most of the historic buildings are grouped and sited in very specific relationships, with houses and industry in small legible clusters, some of which survive today in form rather than use, including the Ram Brewery and 70 High Street (formerly residential) and at Wentworth House in Dormay Street. This is further reflected in the network of alleys and small roads linking the central area with its industrial surroundings. For similar reasons the Huguenots built a number of quality houses on East Hill, as well as the burial ground central to the Conservation Area.

Industry

Wandsworth was, above all else, an industrial town, and although development is transitioning away from this use, the memory of defunct industries is a part of the character of the Conservation Area. It can be found in the form of reused and related buildings, the morphology of the town, and its street names. The margins of the Thames, north of the Conservation Area, was an industrial hinterland of wharves, works, and warehouses from an early date and to some extent retains an industrial presence, despite recent Thameside redevelopment.

The development of the Surrey Iron Railway and its dock (later known as the Cut) and railway wharf also assisted Wandsworth’s industrial development. The Railway was an eight-mile line linking the dock to Croydon and there were short branches to various warehouses and mills in Wandsworth and elsewhere. Although the Railway only operated from 1802 to 1846, it influenced the topography of the Conservation Area greatly, with the section of track west of the Ram Brewery becoming Ram Street (formerly Red Lion Street) and the location of one of its bridges influenced the formation of Buckhold Road.

New intensive industries established in Wandsworth in the 19th and 20th centuries included gas manufacture and storage; the blending and refining of oil; chemical processing; the so-called ‘noxious trades’ producing artificial manure, soap, glue, and candles; industrial engineering (manufacture of motor vehicles, household appliances, and printers’ plant); and electrical components and equipment. Of these new industries, the manufacture of gas conceivably had the greatest impact on the development of the town. The Wandsworth Gas Company was established in 1834 and opened its works the following year on the west side of Fairfield Street, where the last remaining gasholder stood until recently coming forward for development. By 1907 Wandsworth gas was the cheapest in London, and the demand was such that the company had expanded to occupy a large swathe of northern Wandsworth with a substantial river frontage. The raw material (coal) was supplied to the wharves by colliers and a coal-discharging pier with hydraulic cranes was built in 1934. The Company was nationalised in 1949, and the works closed in 1971 with the introduction of North Sea gas.

In the 20th century, the Metropolitan Borough Council developed new areas to host light, small-scale industry, such as the Osiers Estate, to the east of Point Pleasant in 1912-20. The post-war period saw a steady decline in the town’s industrial base, despite its diversity. Some companies outgrew their Wandsworth premises and moved out of the capital while others claimed a decline in suitably skilled workers in Wandsworth. Unwanted sites were redeveloped for commercial and/or residential use, and others fell derelict.

More recent development has seen continued revitalisation of former industrial sites, both within the Conservation Area, and within its setting, including the aforementioned Ram Brewery Complex, the former gasworks, as well as the light industrial area comprising the Wandle Delta. Regeneration of these typically larger sites is often residential led mixed-use developments, often with taller building developments, which is slowly changing the character and appearance of the Conservation Area, as well as its wider setting. The potential redevelopment of further former industrial and of commercial areas, such as the Southside Shopping Centre, will continue to put pressure on development within the Conservation Area, particularly along the High Street.

Fig. 15: Contemporary tall building development contrasts with smaller scale historic development

Part Two: Conservation Area Appraisal

Location and Setting

Wandsworth Town is situated between the town centres of Clapham Junction in the east and Putney to the west, centred on the River Wandle which flows north into the nearby Thames.

Topography

Wandsworth lies in a valley at the lowest bridging point of the River Wandle, a few hundred metres upstream from its confluence with the Thames. The town is based on an historic road pattern focused on the river crossing and reinforced by the river itself, and later developments such as the Surrey Iron Railway, insertion of Armoury Way, and more recently, redevelopment of the Ram Brewery Complex. The dominant feature of the town centre is the sweeping curve of the ancient main road (current A3) rising up the valley sides.

Buildings and Townscape Overview

The layout, and thus appearance and experience of the Conservation Area, is dominated by the route of the High Street/A3, and to a lesser degree by Armoury Way and the River Wandle. These busy roads and routes have influenced the layout and type of development, with the most dense, urban character at the junction of the three. Historic remnants remain obvious, including short laneway/offshoot roads to the busy High Street, and pockets of workers cottages which are reflective of Wandsworth’s industrial origins. Primarily a historic town centre, the piecemeal and organic growth of the area has resulted in a richly varied and much altered townscape, and the character of much of the area is defined by this diversity.

Fig. 16: One of the housing typologies within the East Hill character area

Although there is a high degree of variation within the Conservation Area, there are general townscape features which are relatively consistent. Residential buildings are typically two storeys and semi-detached or terraced, while commercial buildings generally have three storeys, with shopfronts to ground and residential (or office) above. Brick is the predominant building material, with stock and gault brick in the peripheries and red brick in the centre. Institutional buildings, such as churches, libraries, and civic buildings, are evenly dispersed though the area, indicative of the origins of the town where mixing work, worship, and housing, was typical.

Fig. 17: Terraces of 3 storeys with commercial to ground floor are common throughout the Area

Contemporary changes to townscape have primarily occurred in the urban centre of the Conservation Area and immediately within its setting, prompted by the Southside Shopping Centre and the redevelopment of the Ram Brewery Complex. This has resulted in a more varied character, with contemporary building materials, styles and scale, introducing tall building development and a more mixed-use building typology.

Fig. 18: Contemporary buildings within the Ram Quarter

Despite the rich variation of the area, there are legible groups or sub-areas which have a shared character and history and are outlined in further detail below. Within each broad area there are further subdivisions, reflecting the complexity of urban development and variations in the overall character.

Spatial Analysis

As the Conservation Area is focused along the route of the A3/High Street, it is primarily experienced in a linear fashion, built up on each side, giving a sense of an enclosed urban centre which dissipates at each end where there is a more suburban character. The gently curved road offers shifting views as one travels along it, with All Saints’ parish church strategically located at the central bend, and a second subtle change of course occurring further east at the bridging point of the Wandle.

At the extreme ends, there are early examples of larger scale housing, remnants of wealthier inhabitants who could afford to live just outside of town, while the centre and its offshoots are characterised by commercial and industrial remnants, interspersed with surviving terraces of small-scale workers cottages.

Formal spaces are few, with the bulk of the Area expanding organically as a result of an influx of industry, and with it, an increased population. Major planning interventions have also greatly impacted the area, such as the widening of the High Street and the insertion of Armoury Way, but the consequential impact on development still was ad hoc rather than formally planned. Smaller formal spaces are evident regarding individual sites, such as the land surrounding churches and large groups of speculative housing, as well as within the Town Hall Complex and the Civic character area. Rather than being a key feature, these smaller formal spaces contribute to the immense variety experienced within the Conservation Area.

The Conservation Area is set within a shallow valley, the lowest point being at the River Wandle, and gently slopes up to the east and west. This allows for longer views from the extreme ends of the Conservation Area, with taller building development often visible. Local views are often transitional given the density of development, but often focused on institutional buildings by nature of their larger scale and more prominent placing.

Traffic dominates the Conservation Area and greatly impacts how it is experienced and perceived. The bulk of the Conservation Area is focused on Wandsworth High Street / the A3, part of the ‘gyratory’ which drives traffic from surrounding areas thorough the historic town centre. Traffic creates a sense of separation, both visually and physically, which has affected the quality of the urban fabric and public realm, while the resultant noise and pollution has impacted air quality and makes the area less attractive to pedestrians and cyclists. The infrastructure required for traffic has also greatly influenced the layout and development of the area, such as the widening of roads and subsequent removal of historic buildings, as well as its character and appearance through signage and traffic control systems. As part of the ongoing redevelopment of the town centre, including the ‘Ram Quarter,’ there are proposals to improve traffic flow and decrease traffic dominance, amongst other public realm improvements. Proposals by Transport for London (TfL) and the Council to reconfigure the Wandsworth Gyratory provide a significant opportunity to support both the Mayor’s and Wandsworth’s ambitions for positive placemaking, which would also lead to improvements and enhancements of the character and appearance of the Conservation Area.

Long Views

Long views are possible from the east and west toward the centre, where taller building development breaks above the otherwise consistent building lines – primarily Sudbury House, Wandsworth Exchange, and Bronze Wandsworth (18 Buckhold Road).

Fig. 19: View from East Hill toward the High Street with taller building development

Fig. 20: East Hill to Sudbury/Wandsworth Bronze

Fig. 21: View from East Hill along Fullerton Road

Fig. 22: View from West Hill with Sudbury House, Wandsworth Exchange breaking above

Fig. 23: View from Putney Bridge Road

Townscape Details

Hard Landscaping

Footways are for the most part surfaced in large Yorkstone pavers with granite kerbs, which are quality finishes. There is value in their consistent treatment. Secondary streets typically converge with a main road via a short patch of brick in various bonds and colours. The treatment of laneways off the High Street is fragmented, with some good surviving setts, such as at Dutch and Chapel Yards, reflecting their historic origins and making a positive contribution to the character and appearance of the area, while others have been paved over as part of wider developments.

Given the significance of the through roads and the extent of traffic, the bulk of street furniture is related to its circulation, in the form of traffic lights, pedestrian crossings and road signs. These are all of a standardised appearance and often clutter the pavements.

Fig. 24: Chapel Yard with surviving setts

Trees and Soft Landscaping

Both trees and other forms of soft landscaping are uncommon to the Conservation Area and do not make a substantial contribution to its character and appearance. Street trees are occasionally placed at the convergence of roads or around larger buildings, which are set back from the road, but even this is inconsistent. Other trees are typically only evident in private gardens and visible given the smaller scale of residential buildings. In primarily residential areas, soft landscaping is more apparent, due to small front and deep rear gardens rather than public landscaping.

Open space is also lacking within the Conservation Area and is primarily limited to the former burial grounds at Garratt Lane and The Huguenot Burial Site (Mount Nod Cemetery). Though both make positive contributions to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area by nature of their openness and rarity, neither makes a significant contribution to the overall appearance or experience, but instead, are appreciated in the context of their respective character areas and will therefore be analysed later in this framework.

Street Furniture

Lamp columns are inconsistent, with only a few very simple classic posts surviving in the area of East Hill – the majority of the remainder are modern and unremarkable, typically black on main roads and grey in residential areas. Telegraph poles are traditional timber. Cycle parking is limited and primarily located along main routes, and in a simple Sheffield stand style.

Architecture

The evolutionary character of town centres, shifting to reflect and attempting to meet the needs of its occupants, in conjunction with advancements in ways of life and technologies, results in a complexity of urban development and variations in their overall character. While this document identifies sub-areas that have a more obvious and legible shared character and appearance below, this section will broadly outline common styles, materials, and features, which are evident and relatively consistent throughout the Conservation Area. Given the variety of the area, the descriptions are not exhaustive, and where clear variations exist, these will be addressed within the appropriate character area descriptions.

Residential – Residential buildings are predominantly Victorian, with some pockets of earlier Georgian houses surviving. Contemporary housing is primarily provided in flats which are part of mixed-use developments. The scale and design of residential buildings varies from simple worker’s cottages to speculative developments, to robust villas. Despite a range of scales, housing remains typically terraced or semi-detached, and almost exclusively two storeys.

Fig. 25: A Victorian terrace in East Hill

Commercial and Shopfronts – Commercial premises and historic shopfronts are predominantly within three storey terraced groups, which have a shopfront to ground floor and residential (increasingly mixed-use) above. Shopfronts appear in almost all character areas, and there are some good examples of surviving historic shopfronts and high-quality modern insertions. Many are, however, poor and some have inconsistency in their design and appearance.

Fig. 26: Attractive shopfronts within the ground floor of a mansion block

Figs. 27 Well-maintained historic shopfront

Figs. 28 Well-maintained tile entrance

Community Buildings – Civic buildings and places of worship are interspersed throughout the Conservation Area, which is reflective of its non-conformist and industrial origins. These buildings are often placed alongside commercial or residential buildings and form important parts of consistent streetscapes and building lines, only marginally set back and with minimal formal planned spaces. The status of these buildings is typically illustrated by their larger scale and use of building materials, frequently employing stone or terracotta for architectural embellishments.

Contemporary Development – more contemporary development has generally replaced infill buildings which were constructed in place of bomb-damaged buildings and therefore have a larger footprint than the otherwise tightly knit terraces most common to the area. They also occupy much of the site of the former Ram Brewery Complex. These developments are often to a much larger scale, projecting well above the typical 2-3 storeys prevalent within the Conservation Area, and are mixed-use in nature. Materials and styles are generally complementary but clearly contrast with the historic environment, employing various shades of brick and modern cladding. Modern design elements, such as extensive glazing and amenity spaces like balconies, also create visual contrast with the regular / consistent, simpler historic forms which surround.

Windows make a substantial contribution to the appearance of an individual building and can enhance or interrupt the unity of a terrace or semi-detached pair of houses. The Conservation Area contains a wide variety of window styles, and many unsympathetic replacements, but it is important that a single pattern of glazing bars should be retained within any uniform composition. Generally, windows follow standard patterns/styles. In Georgian and early-mid Victorian terraces, each half of the sash was usually wider than it was high, but its division into six or more panes emphasised the window opening’s vertical proportions. Later Victorian and Edwardian buildings often employed a simpler pattern, with the top and bottom sash either having one large pane, or a single central glazing bar. Windows reduce in size and have simpler surrounds as they rise through the building demonstrating the hierarchy of internal spaces.

Window frames are most commonly white painted timber, and where uPVC replacements have been allowed, these are mostly white and reflect the historic glazing pattern. Casement windows are uncommon, and predominantly are a result of later, unsympathetic interventions.

Bricks are the most common building material within the Conservation Area, with residential properties primarily comprised of stock and yellow brick, while commercial premises are generally red brick. Public buildings are also generally constructed of brick, including churches and schools. Brick is also often used in contrasting colours as a decorative embellishment.

Contemporary development has also employed brick skins to various degrees, generally paired with other more modern materials and executed in colours which are not necessarily common to the general palette of the area.

Roofs are most commonly finished in black slates or red tiles, and while extensions have become more commonplace to commercial buildings, residential properties remain relatively unaltered. Where commercial premises have been altered, this has been carried out through mansard style roof extensions in lead or zinc, set back from the parapet, or through simple, consistent dormers into the existing roof slope.

Character Areas

There are seven sub-areas to the Conservation Area, each with a distinct character:

- West Hill

- Putney Bridge Road

- Armoury Way (Rename?)

- High Street

- Ram Brewery

- Civic

- East Hill

Character Areas

Fig. 29

Sub-Area 1: West Hill

Summary Description

The West Hill sub-area comprises the buildings lining West Hill from Lebanon Road east to Putney Bridge Road, and the triangular plot formed by the junction of Merton and Broomhill Road, extending south to enclose the grounds of West Hill primary School. The area houses a number of prominent public buildings, including the Church of St. Thomas à Becket and the former West Hill Library, marking the western boundaries of the Conservation Area.

The remainder of West Hill is primarily residential in character and demonstrates a wide variety of buildings and plot widths, reflective of its 18th century origins as a linear collection of townhouses and villas outlying and overlooking the former village of Wandsworth. The sub-area contains the highest concentration of 18th and early 19th century houses within the Conservation Area.

Fig. 30

Townscape

The varied townscape within the character area is largely defined by the contrast of large-scale public buildings, historic grand villas, and more typically commercial architecture. To the west, the Church of St. Thomas à Becket (Grade II) and the former West Hill Library (Locally Listed) (Figs. 31&32) pair with West Hill Primary School (LL) and Wandsworth Police Station (LL) to the east. These important buildings illustrate the status of the character area, which was quite wealthy and merited larger-scale development to serve its local residents.

Fig. 31: Church of St. Thomas à Becket

Fig. 32: West Hill Library

The Perpendicular Gothic style Church of St Thomas and the former library are robust buildings which are slightly set within their grounds, and serve as local landmarks, acting as the western marker or ‘gateway’ to the Conservation Area. Together the buildings form an institutional group. A collection of grand early 18th/19th century villas (Grade II) survive to the south of West Hill and reflect early residential development (Fig. 33). The houses are of a similar style and have architectural and aesthetic value as an attractive group of houses along West Hill, which initially would have been outside the village of Wandsworth. The larger houses represent an ambitious speculative development of large townhouses for a more middle-class occupant, possibly industrialists. Adjacent to the group is 37b (Fig. 34), a small, recessed weatherboarded cottage, heavily modified, but the extant weatherboarding has a rarity value as the last survival in Wandsworth of a once common method of cladding vernacular houses.

Fig. 33: Grand listed villas are some of the earliest residential buildings in the Area

Fig. 34: 37b West Hill

At the east and south of the area are two more institutional buildings which have a grander scale. The Queen Anne style Police Station is well-executed and of aesthetic value and is also a representation of 19th century civic reform in Wandsworth. To Merton Road, the elementary school of 1891 by T.J. Bailey is a typical London Board school, of three storeys with a picturesque silhouette including Dutch gables and a turret. The elevations are also in a Queen Anne style.

Fig. 35: Police Station

Fig. 36: West Hill Primary School

Much of the remaining development contrasts somewhat with the rest of the Conservation Area in that it is almost entirely three storeys, including both residential terraces, a small flat conversion, and commercial premises. This scale drops to two storeys at the corner of Putney Bridge Road with a pair of Grade II listed cottages at 140-142 Wandsworth High Street, which marks an area of transition to smaller scale workers cottages, which become more prevalent to the north, including Bush Cottages and those within the adjacent Putney Bridge Road character area.

Spatial Analysis

The linear section of the character area feels slightly more open than the more dense, urban feel of the town centre, as buildings are typically detached with gaps between, or set back from the road, allowing for glimpsed views through properties to development and open spaces beyond. Despite a high brick wall running along the north side of West Hill and obscuring buildings, mature planting above gives the impression of open space behind and softens the appearance of the solidly built wall.

West Hill is also one of the highest points in the Wandle Valley which slopes down toward the Wandle, and therefore longer views are possible toward the town centre, heightening the sense of openness and connectivity to the centre.

At the approach to Merton Road, the road widens to create a small, paved island at the junction, which also creates a sense of openness. The various building groups are legible as set pieces in this context, rather than a solidly built streetscape, broken up by the roads branching away, and more obvious variation in scale to this half of the character area.

Architecture

The dominant building material is brick with gault, stock, and red brick all common – institutional buildings are more highly decorated in stone or terracotta, while commercial and residential terraces have simple brick detailing. Render and paint are evident but uncommon and generally restricted to individual elements or storeys rather than entire façades.

Windows are generally timber sash and glazing bars would have been common to the large villas, public buildings, and listed cottages, though many have been replaced without glazing bars or in unsympathetic uPVC. Similarly, the terraces would have had sashes with single panes or a single central glazing bar, but the majority have been replaced with unattractive modern replacements and casement windows which detract from their character and the consistency of the groups.

Roof forms to terraces are generally butterfly or gabled, while historic villas have gambrel roofs. Interventions are uncommon, with only a small number of dormers and rooflights present, and these are well concealed.

The weatherboarding has a rarity value as the last survival in Wandsworth of a once common method of cladding vernacular houses.

Shopfronts

Shopfronts are in generally good condition with many historic fronts, or elements, being retained, and only a small number of contemporary shopfronts, which attempt to follow traditional design principles, but in inappropriate contemporary materials. Signage is also mixed with some good traditional styles and other inappropriate boxed fascia. Nos. 6-8 have been heavily modified and remain in an extremely poor condition.

Nos 1-21 West Hill is a terrace group fronting the corner of West Hill with Merton Road, and have shopfronts inserted to their ground floor with residential above and is a transitionary group from the commercial High Street to the more residential character of the west. However, several of the terraces, though the shopfront has been retained, have been converted to residential use. This has detracted from the character of the area and intrudes on active street frontage to the remainder of the group.

Sub-Area 2: Putney Bridge Road

Summary Description

The Putney Bridge Road Area is a linear section which branches north from the West Hill and High Street sub-areas, extending from the junction of Putney Bridge Road and Armoury Way to the railway bridge. The north section is focused on the development between the streets which comprise the junction at Putney Bridge Road, Oakhill Road and Point Pleasant. This includes notable examples of 19th and early 20th century terraced housing: Nos 1-10 (consecutive) Oakhill Place are locally listed, Nos 155- 175 (odd) Oakhill Road (155-171 Grade II), and 8-14 Prospect Cottages. This small group of primarily workers cottages is interrupted by the railway line passing through and are some of the earliest terraces in the area. At the junction itself is the locally listed Queen Adelaide Public House (PH), which marks a transition southward to a more mixed character, further transitioning to commercial character toward the High Street.

The west side of the road is defined by a long wall which extends south from Oakhill Road to the police station and probably marked the boundary of the former training college at the Convent of the Sacred Heart. The east side of the road has an irregular assortment of buildings, a mix of commercial and residential, notably the former Wheatsheaf PH, the locally listed Hop Pole PH, and early 18th century houses at 20-24 Putney Bridge Road (Grade II).

The southern end of the area has the former All Saints National School, converted to commercial premises, and 59-61 Armoury Way, the former showroom of Allan Taylor, dealer, and vehicle manufacturer, which is reflective of the transition to motor and light industrial character that historically dominated Armoury Way.

Fig. 37

Townscape

The sub-area is transitionary in its character and is a roughly linear section of the Conservation Area, branching at the northernmost point to include an enclave of workers cottages, which forms one of the extreme ends of the Conservation Area.

The north end of the area is characterised by simple brick cottages of two storeys and generally a single bay wide, with gable or butterfly roofs (Fig. 38). The Grade II listed terrace to 155-171 Oakhill (Fig. 39) are actually flats designed as a row of four cottages with commercial laundry behind and are two-storey with attic and projecting front gables in an Arts and Crafts-style. The railway and Putney Bridge Road sever a short terrace and the small group at Prospect Cottages to the north. These cottages are slightly elevated, with brick detailing, butterfly roofs, parapet, and porches. The cottage group are of illustrative value as an example of early workers’ housing, stimulated by the growth of Wandsworth industries.

Heading south along Putney Bridge Road are two typical Public Houses, with the Queen Adelaide (Fig. 40) and Hop Pole (Fig. 41) being locally listed, as well as fragments of now lost groups of more cottage housing. The Queen Adelaide is a little-altered, mid-19th century Young’s pub in a Tudor style, which enjoys a prominent position at the convergence of Putney Bridge Road and Point Pleasant and has aesthetic value as a representative of the diversity of pub architecture and illustrative value as a well-established Public House. The Hop Pole is a two-storey, stucco fronted, early-19th century pub with a balustraded parapet and pediment bearing its name. These features and its intact exterior lend it aesthetic and townscape value, and it now serves as a focal building along the fragmented Putney Bridge Road. Both pubs serve as a reminder of Wandsworth’s heritage of breweries and public houses.

Continuing south from the Hop Pole are an irregular assortment of buildings, illustrating the fragmentary character of this part of the Conservation Area, which was heavily influenced by the introduction of Armoury Way. These include a pair of Edwardian workers cottages, the remains of a terrace of four, the other pair replaced by an unsightly advertising hoarding. Further south, Lambeth Court represents a 1960’s block of flats in Frogmore.

A group at the corner of Armoury Way includes the former Wheatsheaf PH (now heavily altered and in residential use) and Nos. 20-24 Putney Bridge Road (Grade II). These 18th century buildings have aesthetic value as an attractive group, an additional example of the importance of the brewing industry, as well as an illustrative value as a remainder of 18th century ‘ribbon development’ along the route to Putney Bridge. The houses are also illustrative of a more ‘middle class’ type development, belonging to the tradesmen and industrialists responsible for the growth of Wandsworth, in contrast with the wealthier Villas of West Hill. The former National School and surviving lodge house to the west of the Road compliment this group.

To the south side of the Junction is the large former showroom of Allan Taylor, of c.1950 but in the streamlined, moderne style typical of the 1930s, with a central finned clock tower. At only a single storey with a wide footprint, it offers visual interest to a busy corner and is indicative of the automotive industry which grew in importance to Wandsworth after the arrival of Armoury Way. At the southern edge of the areas is a short three storey terrace with shopfronts, reflective of the commercial nature of the High Street, and a pair of simple worker’s cottages.

Fig. 38: Prospect cottages are a good example of early worker’s cottages

Fig. 39: 155-171 Oakhill, Grade II Listed

Fig. 40: The Queen Adelaide Public House

Fig. 41: The Hope Pole Public House

Fig. 42: 20-24 Putney Bridge Road, Grade II

Fig. 43: Former showroom of Allen Taylor

Sub-Area 3: Frogmore

This small character area comprises the properties east of Frogmore and west of the River Wandle, a historic enclave that was fragmented from the historic centre by the introduction of Armoury Way, making the relationship between the two sections difficult to appreciate. Armoury Way was constructed in 1938 as a by-pass to relieve traffic along Wandsworth High Street and York Road, severing the group from the High Street and routes to the Wandle and Thames. The degradation of the relationship with the town centre has impacted the sense of place by making the area less attractive to pedestrians and compounding a sense of segregation - physically, visually, and through erosion of the experience of a historic setting.

Still, fragments of the historic townscape exist, with good surviving buildings at Nos. 22-24 Armoury Way and The Crane Public House (Locally Listed) (Fig. 45), which address a small triangular open space at the intersection of Wandsworth Plain, Frogmore, and the Causeway. No. 22 terminates the view northwards from Wandsworth Plain and forms part of the setting of All Saints’ Church and Church Row. The townscape value of the houses and the way they relate to Wandsworth Plain helps to mitigate the intrusion of Armoury Way. Similarly, the nearby Crane Public House is an important symbol of the presence of the brewing industry in the town, and together, with the intervening three terraced houses and Grade II listed Wentworth House, form a notable pre-20th century group, which contributes townscape value to the degraded environment of Armoury Way.

Fig. 44: The Crane Public House, Locally Listed

Fig. 45: Nos. 22-24 Armoury Way and adjacent terrace fragment

Fig. 46: Grade II listed Wentworth House

Fig. 47

Summary Description

The High Street sub-area forms the core of the Conservation Area and includes some of the oldest surviving buildings within it, reflecting the early origins of the town. The area is primarily comprised of a ribbon of development running east-west along the High Street, spreading outward from the River Wandle which formed a key aspect of the industrial origins of the area. The character of the area is divided into two sections, briefly interrupted, but complemented by, the Ram Brewery site, which comprises its own sub-area, but is inherently linked to the development of, not only the High Street, but of the town as a whole.

The west section runs from the junction of the High Street and Putney Bridge Road to the Wandle, while the smaller east section is centred around the High Street and Ram Street/Garratt Lane, extending southwards to include the Former Burial Ground in Garratt Lane and eastward to the Civic sub-area.

The character area has the greatest concentration of quality buildings and townscape assets, with a marked sense of arrival provided by the topography of the Wandle valley. All Saints Church (Grade II*) is strategically placed at the focus of the curved road. The junction of Garratt Lane and Ram Street with the High Street also marks the change to the commercial core of the town. The Southside Centre has a largely negative effect on the townscape, but The Ram Brewery (listed Grade II*) presents an impressive facade that provides an important and unique identity and character to the town. The River Wandle should form an important element at this point but is largely hidden from view. There is great potential to increase public awareness and visibility of the river.

Townscape

The High Street sub-area has the highest concentration of buildings and demonstrates the greatest variation in style, though there is a good level of consistency remaining in its scale and from. Buildings generally range from two to four storeys, with three the predominant building height. The upper/attic storey is often recessed with dormers, and this is evident on both historic and contemporary additions. Only modern buildings break this pattern and are typically of a larger scale.

Fig. 48: All Saints Church, 1885, prior to the 1899-1900 restoration of the tower

Fig. 49: All Saints Church in 2022 with Church Row and Ram Brewery in background

Fig. 50: Grade II* Church Row

The Grade II* All Saints Church (Fig. 49) forms the central focus of the High Street, with surrounding scale and layout responding to its prominence. The church is one of the few buildings set within its own grounds, heightening its sense of importance. The adjacent 18th century Grade II* Church Row is some of the earliest surviving town houses in the area (Fig. 50).

Still legible, and deeply characteristic of the area, is the dense medieval grain of the town, with long, narrow burgage plots with narrow frontages to the high street, some of only a single bay. These solid rows are occasionally interrupted by narrow alleyways leading to backland plots. These alleys usually lead to a more intimate space, with a decrease in scale of development away from the High Street – more recently, however, backland development has been to a much larger scale, and this hierarchy has been lost. The historic relationship is well illustrated at Nos. 110-124 (even) (Fig. 51) Wandsworth High Street, and the adjacent Carter’s Yard. Though the façades of these plots were variously rebuilt throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, their scale, form, and simple design is reflective of the diverse character of the former village. Many have become cluttered with modern, unattractive shopfront insertions, and projecting signs/satellite dishes.

Fig. 51: Nos. 110-124 Wandsworth High Street and the characteristic alleyway of Carter’s Yard

Fig. 52: Alleyway at Chapel Yard

The double curve in Wandsworth High Street gives rise to ‘progressively changing vistas along its length’. The pivotal building is All Saints’ Church (Fig. 49). Nearby is the Wandle bridge, which was ordered to be repaired by Queen Elizabeth I in 1602, and subsequently rebuilt in 1757, 1820 and 1912 (Fig. 51).

Fig. 53: Bridge over the River Wandle c. 1910

Early surviving buildings in the High Street sub-area include 86 Wandsworth High Street (Fig. 54), a single-bay, early 19th century house in stock brick. Its first-floor window is recessed into a large panel with a three-centred arch.

Fig. 54

A large concentration of buildings along the southern side of the High Street were constructed during the same period in the early 20th century because of a road widening scheme in c.1913, which saw the demolition of many earlier buildings (Fig. 54). Nos. 107-209 were subsequently rebuilt, each following a different design, scale, and form, though sharing variations of a Neo-Georgian style. This includes common elements such as rusticated quoins and ashlar keystones, which ties the character of the shopping parade together, but avoids homogeny, giving the impression of earlier, ad hoc development more typical of a High Street / village centre.

Though the widening of the road impacted the sense of enclosure that would have been experienced historically, replacement buildings followed the historic grain, and the dense, terraced streetscape maintains an element of it. This is emphasized by the absence of gaps between buildings, demonstrating the varied and organic development of the High Street.

Fig. 55: Nos.141-143 (odd) Wandsworth High Street is a fine Edwardian Baroque refronting of an older building in dark red brick and ashlar. The building, formerly a bank, has a segmental pediment of ashlar with a cartouche bearing the date 1914 and the name David Greis. The adjoining 147-155 Wandsworth High Street (and probably Nos. 157-161 also) were completed by A. Edwin Westerman around 1932 in a neo-Georgian style. They are fronted in red brick with ashlar dressings and brick quoins.

Post-war rebuilding schemes sometimes amassed several plots which resulted in the creation of monolithic commercial/office blocks which were set back from the road. These have subsequently been redeveloped into modern mixed-use buildings, often occupying multiple plots, and being of a much larger scale and height. These over-scaled developments diminish the historic character of the Conservation Area and intrude on the setting of many locally and nationally designated heritage assets. The largest such development, outside the Conservation Area, is the Southside Shopping Centre, the development of which included four residential point blocks which dominate the smaller scale buildings of the Conservation Area. Sudbury House, the tallest and most central block, has been reclad and is wholly out of scale with earlier development, and is an unattractive feature visible throughout the Conservation Area. More contemporary development has followed suit, and taller building development has taken place both around Southside and within the Conservation Area itself, which has changed the character and appearance of the Conservation Area, as well as its setting.

The most recent tall building development has occurred to the east of Southside, at the Wandsworth Exchange (Fig. 55). The central tower is clad in grey brick which is an uncommon material and contrasts with the predominantly red brick palette of the High Street. The site is slightly set back from the street, it is taller and equally as imposing as Sudbury House, and visible in multiple views throughout the Conservation Area. The simple rectangular tower is not overly responsive to the surrounding context and the angular peak adds limited visual interest while failing to mitigate visibility or offer a sense of slenderness/stepping back to the top of the tower. Further tall building development is expected to the north, within the Ram Brewery character area, creating a contrasting modern town centre to the historic High Street.

Fig. 56: Taller building development at Sudbury House and Wandsworth Exchange have a great impact on the character of the Area.

Open Space, Gardens, and Trees

The High Street sub-area has one of the few open green spaces within the Conservation Area at its southern boundary. The Old Parish Burial Ground, also known as Garratt Lane Old Burial Ground, was created in the 1830s with burials taking place until the 1930s and is now maintained as a public park (Fig. 57). Some original gravestones and tombs remain, and the flat, rectangular park provides a green relief on the otherwise busy shopping street. Given the density of development along the High Street, the park mainly contributes to the streetscape to Garratt Lane to the east and has the feel of an enclave within an urban setting.

The character area is otherwise vacant of any meaningful gardens, plantings, street trees, or public open space, instead characterised by a busy High Street environment with hard landscaping and a busy throughfare. The introduction of new green and open spaces would benefit the appearance of the High Street and reclaim it as a pedestrian friendly space. This can be illustrated to a degree by the small, paved area to the north of the Southside shopping centre which hosts a lively food market that attracts a greater amount of people than the traffic heavy extremities of the area.

Fig. 57: Garratt Lane Old Burial Ground

Shopfronts

The High Street has the highest concentration of shopfronts in the Conservation Area and while there are isolated examples of high quality and historic shopfronts, many are overly contemporary, ignoring traditional elements, materials, and features, and give the impression of an inconsistent and lower quality commercial area. The use of plastic signs, facias, and commercial branding, combined with inappropriate methods of illumination, detract from the historic character of the host buildings, and create a visual disparity, both between the shops and their host buildings, and between the shopfronts themselves. Fine shop fronts with panelled risers, big plate-glass windows and fascia lettering survive at 106 (‘W.G. Child & Sons, High Class Taylors’ and 141-143 (odd) Wandsworth High Street (Fig. 27&28).

Shopfronts along the High Street also consistently use solid or roller shutters which are often housed in projecting shutter boxes, both of which have a negative impact on the character and appearance of the Conservation Area (Fig. 59).

Fig. 58: Typical shopfront of varying quality

Fig. 59: Low quality insert with surviving corbels, roller shutters with box fascia storage

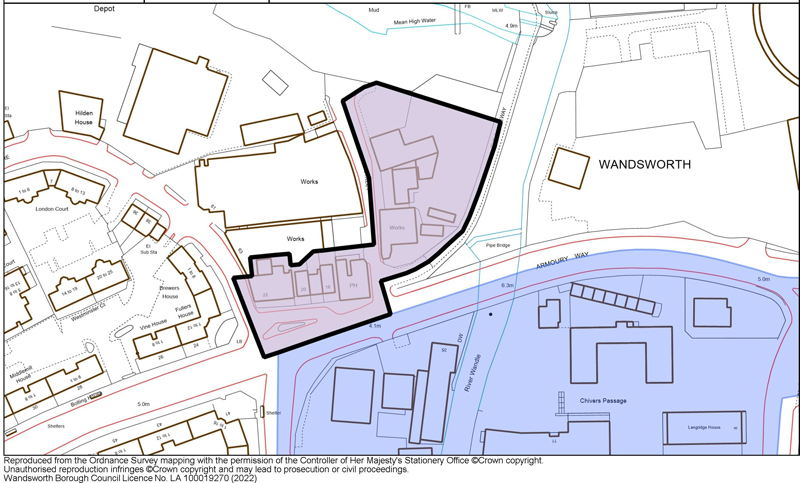

Sub-Area 5: Ram Brewery Area

The sub-area comprises the Ram Brewery site which is bounded by Wandsworth High Street, the river Wandle, Armoury Way, and Ram Street, two sections of 19th century terraced workers’ housing on Barchard and Fairfield Streets, with a corner pub, as well as the land west of the Wandle, currently occupied by the former Capital Studios. The character of the subarea is somewhat heterogeneous, multi-phase, and now primarily comprised of contemporary development which complements the remnants of the brewery complex.

Large-scale brewing, occurring at Wandsworth from at least the 16th century, used the Wandle as a source of pure water and to cool the fermenting vessels. Post-war clearance has removed almost all trace of these water-powered and water-intensive industries, the notable exception being the Ram Brewery. Indeed, the lower Wandle itself is today a man-made river channel: diverted, canalised, and culverted for industrial and, most recently, town-planning purposes. The importance of the waterway in the formation of Wandsworth is not reflected by its form, and it remains largely hidden from pedestrian view.

Fig. 60

Townscape

Ram Quarter

The retained outward facing High Street and Ram Street frontages are the earliest buildings on the site and comprise a combination of the industrial brewing complex (Grade II*), The Ram Inn, the former brewhouse at 70 Wandsworth High Street, and the Stables (all Grade II).

It is highly unusual to find a mature and largely complete industrial complex at the heart of a metropolitan settlement, and there are few London parallels. It is perhaps the most distinctive aspect of Wandsworth, and arguably equals the parish church in terms of a landmark, and considering its regeneration, surpasses its contribution and impact to surrounding development. The Ram Brewery buildings collectively reflect the dominant presence of the brewing industry within Wandsworth, and each represents architectural and industrial developments within the site, giving them high historical and illustrative value.

Fig. 61: The former brewhouse (left), Ram Inn (centre), and part of the brewery complex (right)

Fig. 62: Courtyard within the complex with some of the listed structures

Redevelopment of the Brewery Site

In 2012 the redevelopment of the complex was permitted, introducing a mixed-use development comprising alterations and change of use to the retained former brewery buildings. The redevelopment also saw the demolition of much of the 20th century building stock, which was replaced with a comprehensive mixed used development, with new buildings ranging from 2-12 storeys. These buildings are generally lower at the south end of the area to remain subservient to the listed complex (Fig. 63), rising to the north of the area, approaching the Grade II listed stables. These properties are primarily residential led, with mixed-use to ground floor and flats above, and there is also retail, residential units, a small-scale brewery, and a brewery museum. The design of the smaller scale buildings is somewhat responsive to the character of the brewery, incorporating elements such as gabled roofs and red brick, while the larger blocks are more typical contemporary block flats in yellow brick, with cladding to set back upper storeys (Fig. 64).

Fig. 63: Contemporary development to a slightly smaller scale at the south of the complex, with more responsive architecture and materials

Fig. 64: More standard contemporary blocks of flats abut the Wandle

The redevelopment also introduced a degree of new public space to the Conservation Area, and increased access, visibility, and awareness to the much-overlooked Wandle through new pedestrian routes and a new crossing.

Fig. 65: View of the pedestrian route along the Wandle from the new crossing

Although not historically linked to the Wandle nor the Ram Brewery, the west side of the character area has been absorbed into it due to the ongoing redevelopment of the Ram Brewery site. Currently the west side of the character area houses the former Ewart Studios (renamed Capital Studios in 1989), an interesting large purpose-built television and photo studio designed in 1966-67, and various ancillary buildings of no interest (Fig. 66). As part of the redevelopment of the complex, this group has consent to be demolished, to be replaced by a 36 -storey building which will occupy the entire western area.

Fig. 66: Capital Studios building, set to be demolished as part of ongoing Ram Quarter development

Though physically and visually separated by the Wandle, the contemporary design and planned acknowledgment of the river will create a new link between the tower and the Ram quarter, and will form part of the areas’ overall character, as well as the setting of the listed group.

Barchard and Fairfield Street

These properties form a group of surviving workers cottages, including Victoria Place (1839) - a speculative terrace of workers’ houses similar to those found elsewhere in the Conservation Area, particularly Oakhill Place. There are mirrored pairs with shared stacks, of two storeys of stock brick with six-over-six sash windows. The terrace is of illustrative value as an example of early workers’ housing, stimulated by the growth of Wandsworth industries. There is group value in the proximity of the terrace with the Brewery, which also demonstrates the early pattern of development, wherein residential and industry were intentionally not separated.

Fig.67: Victoria Place terrace

Spatial Analysis

Despite its central location and prominent visual presence within the Conservation Area, particularly from the High Street, there is a sense of isolation and segregation to the character area due to the surrounding heavily trafficked roads and the lack of permeability to the north of Armoury Way due to insufficient pedestrian crossings.

There is a small forecourt to the southwest of the site, which is the most obvious and visually appealing point of entry, which leads to a small, informal internal courtyard, which is surrounded by the brewery complex and new buildings, and therefore, has a feeling of enclosure. As one moves deeper into the area, both the Drapers Yard and single through route of Ryeland Boulevard are between blocks which increase in height, and the linear gaps between them prevent views out of the area, enhancing this sense of enclosure. The future conversion of the stable building will likely mitigate this feeling and add a new active set piece.

Fig. 68: View toward stables along Ryeland Boulevard

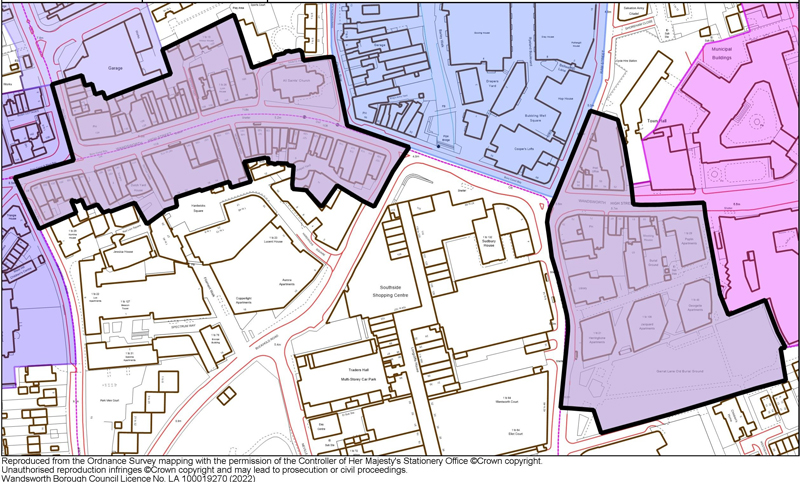

Sub-Area 6: Civic Area

Summary Description

The civic core of Wandsworth Town is dominated by the large, inter-war buildings of Wandsworth Town Hall and South Thames College, both Grade II listed. Originally the Town Hall was planned as the focal point of a five-acre civic centre by Wandsworth Metropolitan Borough Council, but only the Town Hall and Wandsworth Technical Institute were built out. The Town Hall instead forms the centre of a smaller civic space which is comprised of the 1935-37 Town Hall and the 1973-75 Town Hall extension (the latter excluded from the Conservation Area). South Thames College was expanded extensively in 2007/8 in a contemporary style.

These grand civic buildings contrast with the east side of Fairfield Street, which is comprised of early 19th century villas (26-30 Fairfield Street, Locally Listed), as well as a complex of high-quality inter-war housing.

To the south of the area is a good group of buildings including the Brewer’s Inn (Locally Listed) and St. Anne’s Church of England School.

Fig. 69

Townscape

The Civic Area is a concentrated square of development which addresses the busy intersection of the A3/ Wandsworth High Street, with East Hill, with the grand Town Hall and South Thames College dominating the area. Wide verges around the Town Hall are mirrored around the housing estate, which give a sense of openness and importance to the area in contrast with the dense urban centre.

Fig. 70: Aerial photograph of the Civic sub-area from the south-east c.1938. The construction of Armoury Way is evident at top right. © English Heritage

Fig. 71: Wandsworth Town Hall

Fig. 72: Town Hall Entrance addressing the junction, with inter-war housing

Fig. 73: The Town Hall and Town Hall Extension

The Town Hall (Fig. 71) is the most iconic building and stands as an important civic statement, and as a symbol of the presence and authority of local government in Wandsworth. Situated on a prominent corner site, it not only dominates the crossroads, but is visible in emerging views from the west end of East Hill and the north end of Garratt Lane. The gated entrance on the corner is designed as an axial processional route into a civic space with central fountain in front of the entrance. Adjacent to the Town Hall are the Municipal Offices (Fig. 73), which are well designed and add architectural value to the streetscape and overall civic character. In contrast to the Town Hall, the Offices directly address the street, providing a sense of enclosure and a contrast with the later civic buildings of 1935-37 and 1973-75, which are recessed from the building line, and transition to the character of the High Street.

Fig. 74: South Thames College

At the south-west corner the South Thames College building again contrasts with the classical Wandsworth Town Hall (Fig. 74). Its historical value derives from the way in which it represents the contribution of metropolitan government to Wandsworth’s inter-war civic complex.

Fig. 75: The Brewer’s Inn Public House

To the south of the area is a group of buildings which are of a smaller scale but reflective of the development of the town centre. The Brewer’s Inn (LL) holds a prominent position, directly opposite the Town Hall, and this is an important symbol of the presence of the brewing industry in the town. Further south still is an attractive Church of England School (Fig. 76), which has association with St Anne’s Church (Grade II*, outside CA), and townscape value for the cohesion it lends to the characterful but discontinuous Victorian buildings of St Ann’s Hill.

Fig. 76: St. Anne’s Church of England School

Fig. 77: Blocks of interwar housing match the scale of the civic buildings

The northwest corner of the area has a group of inter-war housing (Fig. 77). These robust blocks of flats balance well with the scale of other development in the area, but are clearly of a more residential character, demonstrated through simpler architectural detailing and materials, and the increased setback from the street to provide additional amenity space. At four storeys, this residential building represents an appropriate response to the height and scale of the other buildings in the area.

Fig. 78: Nos. 26-30 Fairfield Street

At the north end of the area are the Locally Listed Nos. 26-30 Fairfield Street, representing a small group of historic buildings which are of illustrative value as the last survivors of the detached and semi-detached middle-class residences built along the southern section of Fairfield Street. They are examples of early suburban development in Wandsworth.

Spatial Analysis

The character area is defined by the monumental civic buildings which are of a much larger scale than the surrounding dense urban grain of the commercial centre and the smaller domestic scale of residential areas. The imposing scale is heightened by the wide spaces between them, with buildings set back from the street, again in contrast to surrounding development, and an important feature of the character and appearance of the character area. While this gives a greater sense of grandeur and openness, it is also undermined by the gyratory system and the overbearing presence of traffic passing through the area toward the High Street. The traffic visually and physically separates the four corners of the important intersection, particularly the south-east as traffic heads west.

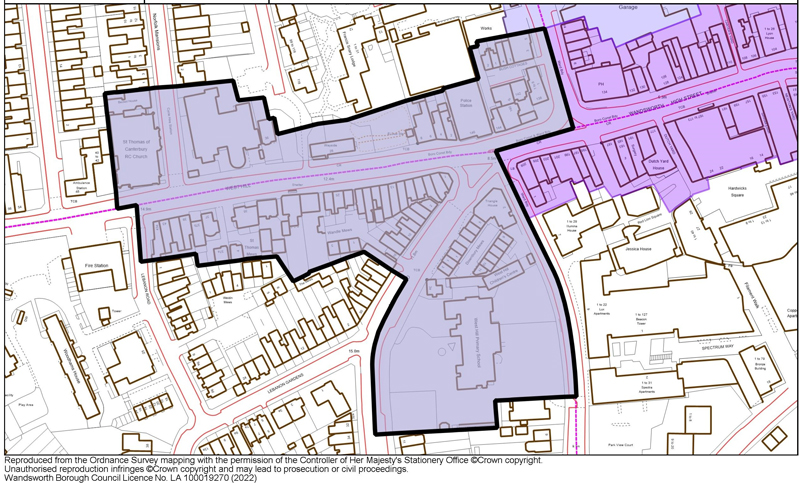

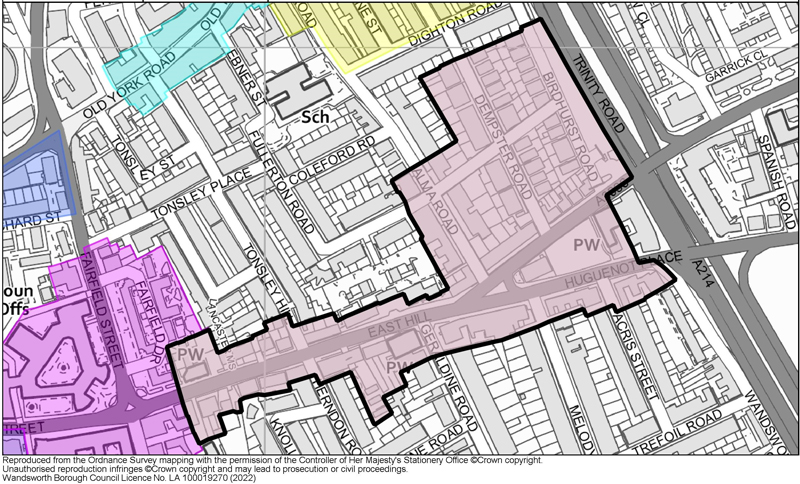

Sub-Area 7: East Hill

Summary Description

The East Hill sub-area runs eastward from the bottom of East Hill to the Roman Catholic Church of St Mary Magdalen. An extension to the north takes in a portion of the terraced housing laid out over Bridge Field. The Elms, Wandsworth House, and 178 East Hill is an important 18th-century townhouse group. Further north is 89 East Hill, a double-fronted early 19th century villa and two early speculative terraces, Craven Terrace and East Hill Terrace.

The wedge-shaped group formed by Book House, the Mount Nod burial Ground, and the Roman Catholic Church of St Mary Magdalen acts as the institutional focus of the late 19th century terraced housing to the north and south, and the eastern ‘gateway’ to the Wandsworth Town Conservation Area as a whole. The speculative terraced housing to the north of East Hill, laid out by two or three local builders, is of uniformly high quality and is a good example of late Victorian suburban development. The grid of streets are primarily terraces of houses built in gault brick with Gothic Revival detailing.

Fig. 79

Fig. 80: Book House, 1911. Source: Wandsworth Heritage Service

Townscape

The townscape and character of the sub-area is transitionary, extending from the mixed use, commercial driven High Street, to the residential eastern extremity of the Conservation Area. This shift is evident in the scale and form of buildings within the character area, as well as in their use. Moving eastward from the Civic Centre, buildings follow a relatively consistent scale of three storeys, often terraced in clear groups which share common architectural detailing. Though some commercial use persists, particularly at the east and west ends of West Hill, building use transitions to residential, and gaps between groups become more common. While the terraces present a relatively consistent building frontage, the streetscape is punctuated by some of the earliest development in the area, such as the Elms and Wandsworth House, which are set back from the road in larger plots, a further visual cue that the character of the area is transitioning, away from the dense urban centre. Places of worship are interspersed throughout the character area, and form an important part of the urban grain, contributing to a consistent street frontage rather than sitting back from, or above it (Fig. 81).

Fig. 81: East Hill United Reform Church (centre left) sits within the streetscape

The eastern edge of both the conservation and character area is signalled by the wedge of development splitting East Hill from Huguenot Place - Book House (Fig. 82), the Mount Nod burial Ground, and the Roman Catholic Church of St Mary Magdalen. This coherent Victorian/Edwardian group forms a key element in the East Hill townscape, situated on a prominent site at the fork of East Hill and Huguenot Place, overlooking the Wandle flood plain and closing the view east along East Hill. The slope of East Hill, rising eastward from the Wandle Valley, forms an important part of the townscape and allows for longer views toward the town centre, while also creating a focal point of the group when viewed from the west. The group fronts a triangular space which is enclosed by late 19th century housing.

Fig. 82: Book House (LL) forms an important marker for the edge of the Conservation Area

Development to both the north and south is strictly residential, with slightly grander and more detailed housing addressing the main road, and more typical Victorian housing behind. The grid of streets is primarily fronted by semi-detached or short terraces of houses built in gault brick with Gothic Revival design, and though there is some variation in their detailing and features, they form a rather consistent speculative group.

Fig. 83: An example of more detailed typology to Huguenot Place

The speculative terraced housing to the north of East Hill, laid out by two or three local builders, is of uniformly high quality and is a good example of late Victorian suburban development. The grid of streets is primarily terraces of houses built in gault brick with Gothic Revival detailing (Fig. 84).

Fig. 84: One of the typical speculative building typologies to the north of East Hill, at Birdhurst & Easthill, the central part of Alma Road, and Dempster Road

Fig. 85: Alma Road typology

To a degree, the commercial character has seeped onto Alma Road, where a secondary commercial street mixes with regular Victorian terraces, likely spurred by the use of the street as a route from the nearby Wandsworth Town Station. The west side of the road has taller three storey development with shopfronts to ground floor, as well as the robust The East Hill Public House, a locally listed building, addressing the corner of Alma and Fullerton Roads.

Fig. 86: Commercial use and building scale continues on the west side of Alme Road, terminating at the East Hill Public House

Fig. 87: Locally Listed Eat Hill Public House

Spatial Analysis

Similar to West Hill, there is a tangible transition from the denser, urban character and medieval grain of the High Street to a more spacious suburban character. Despite the presence of large terrace groups fronting East Hill, the gaps between them and greater presence of side streets leading to surrounding residential areas prevents a consistent frontage and allows for more uninterrupted views throughout the area. The sloping nature of the road up the Wandle Valley also allows for longer views into the Conservation Area, which heightens a sense of openness and connection to the centre.

To the north of East Hill, the scale and use of buildings shifts to a more domestic scale, with speculative residential development in short terraces or semi-detached pairs. The consistent scale and building typologies give the impression of a residential enclave, contrasting with the more diverse main road. As a residential area, traffic is also less common, and gardens form an important feature of its character, contributing to a more suburban feel. While shallow front gardens soften the frontages and create a pleasing streetscape, deep rear gardens allow for longer views through the residential area.

Architecture

The character area is primarily comprised of the speculative Victorian development to the north of East Hill, which, despite some variations through different builders, is of a relatively consistent typology. Terraces to East Hill and Huguenot Place are more varied, with a consistent scale and materiality, typical of their Victorian construction. Approaching the High Street, there are more obvious fragments of earlier development, including simple domestic scale workers cottages similar to those found throughout the Conservation Area, as well as larger dwellings, set back from the road, which represent some of the earliest and wealthiest development in the character area.

Fig. 88: Fragments of earlier housing survive along East Hill

Fig. 89: Pockets of grander development are evident in larger plots set back from the road

Boundaries & Entrances

Fig. 90: Dempster Road c.1925

Historic images indicate that boundary treatments differed by terrace, with Fig. 90 showing a mix of simple timber fencing, brick walls, and low stone walls with short rails above. Few examples of either style remain, and today, boundary treatments within the residential area are irregular, with disparity between even the pairs within the largest terraces. The front gardens of 152-162 East Hill were lost when East Hill was widened in the 1920s. Although predominately brick, there are also examples of render, metal, and timber, or a combination of the various materials. The key element of the boundary treatments is their presence in demarcating a clear front garden, which sets the terraces back from the street, giving the impression of a wider road and a slightly elevated status of home. Despite a variation in materials, boundaries should maintain a consistency in scale and permeability. Walls are most often lower than front bay windows, allowing for the entire façade to be visible, a scale which also allows for views into the front gardens.

Entrances are short, paved areas, and while many have been replaced with pavers or concrete, a good amount of original tile paths survive, ranging from more modest tessellated diagonal black and white patterns to more elaborate and colourful designs, either original or replicated in a sympathetic manner. These paths add visual interest to the streetscape and echo similar approaches taken to terraced housing in adjacent speculative developments, including the Old York Road Conservation Area. The retention, repair, or reintroduction of such detail is of benefit to the character and appearance of the character sub-area.

Fig. 91: Simple diagonal tiles

Fig. 92: Historic patterned evident tiles

Open Space, Gardens, and Trees

The treatment of open spaces within the character area varies greatly, lacking a consistent approach, but the green spaces that do exist make a positive contribution to the more suburban character and appearance of the area, which contrasts with the dense, urban development of the more central areas.

Fig. 93: Mount Nod Cemetary is the only public green space in the character area

The largest open space is the The Huguenot Burial Ground (also known as Mount Nod Cemetery) for Huguenots which was in use from 1687 to 1854 (Fig.93). The burial ground is located between the junction of East Hill and Huguenot Place, and adjacent to St Mary Magdalen Roman Catholic Church. A locally listed historic park and garden, the burial ground also houses a number of Grade II listed tombs restored in 2021. The grounds are primarily grass with mature trees and shrubs dotted around, but planting largely follows the perimeter, marked by an iron rail.

Despite being one of the largest green spaces in the Conservation Area, the grounds are isolated, physically and visually seperated from the surrounding residetnial areas by the busy A3 and bookended by the iconic Book House, and the Oratory of St Mary Magdalen Catholic Church.

Mount Nod represents the industry and wealth of Wandsworth’s Huguenot community and the early table tombs it accommodates are of intrinsic historical and cultural value. As a historic burial ground and resting place of important Wandsworth families it possesses spiritual and commemorative value. It is also significant as a 19th century public garden.

Along East Hill, development typically fronts the street directly, with pockets of relief to the surviving small front gardens of more historic houses, or where newer blocks have been slightly set back to create more formal entrances and amenity space. These pockets most often contain mature trees which offer relief to the otherwise highly urban / High Street feel of the area, though there is a lack of consistency or a formal approach, such as street trees, which could further enhance the area and create a visual conenction to these irregular patches.

Fig. 94: Planting to rear gardens helps create a suburban feel