Battersea Square

Conservation Area Appraisal No.9

Contents

- Part One: Introduction

- Part Two: Conservation Area Appraisal

- Part Three: Management Strategy

- Appendix: Locally Listed Buildings

Part One: Introduction

Outline of Purpose

The principal aims of Conservation Area Appraisals are to:

- Describe the historic and architectural character and appearance of the area which will assist applicants in making successful planning applications and decision makers in assessing planning applications;

- Raise public interest and awareness of the special character of their area;

- Identify the positive features which should be conserved, as well as negative features which indicate scope for future enhancements.

It is important to note that no Appraisal can be completely comprehensive, and the omission of a particular building, feature, or open space, should not be taken to imply that it is of no interest.

This document has been produced using the guidance set out by Historic England in the 2019 publication Understanding Place: Conservation Area Designation, Appraisal and Management, Historic England Advice Note 1 (Second Edition).

This document will be a material consideration when assessing planning applications and as an evidence base for the Local Plan.

What Is a Conservation Area?

The statutory definition of a conservation area is an ‘area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’. The power to designate conservation areas is given to local authorities through the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservations Areas) Act, 1990 (Sections 69 to 78).

Once designated, proposals within a conservation area become subject to the national policies outlined in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), the adopted London Plan policies, and the conservation policies set out in the Council’s Local Plan). Our overarching duty, set out in the Act, is to preserve and/or enhance the historic or architectural character or appearance of the conservation area.

Public Consultation

Public consultation on the draft Appraisal was carried out between the 10th February and 24th March 2023.

This document was approved by the Planning and Transportation Overview and Scrutiny Committee on 4th July 2023 and the Executive on 19th July 2023.

Designation and Adoption Dates

Battersea Square Conservation Area was first designated on 9 November 1972 and has been extended twice before - on 24 May 1989, and again on 28 November 1991. A third extension, to include St Johns Estate, forms part of this Appraisal, as do other small changes to rationalise the existing boundary in reflection of development which has occurred since the establishment of the previous boundary.

This Appraisal was adopted on the 31st of August 2023.

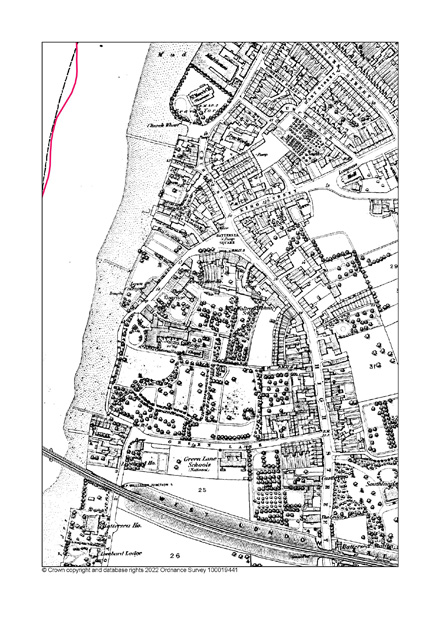

Map of Conservation Area

Summary of Special Interest

The area derives its special character from this village pattern, which though altered over the centuries is still discernible in the relationship the present church has with the settlement clustered around the Square itself and also spread along its access routes, Westbridge Road, Battersea High Street and Vicarage Crescent. The remnants of the older settlement, for example the church, Old Battersea House, and the Raven PH, give a historic perspective to the later Victorian developments elsewhere in the Conservation Area. The continuity of the Battersea Square area as it developed from a sleepy manorial backwater to a more industrialised suburb following the construction of the bridge over the Thames in 1772 can be clearly read in the surviving buildings and settings. Although there have been modern intrusions into the area, Battersea Square still retains its charm as the historic heart of Battersea, around which the later Victorian housing developments and industries burgeoned.

Historic Development

The early history of the Battersea Square area is uncertain, although discoveries of Saxon pottery in Althorpe Grove nearby indicate the presence of a late Saxon settlement centred on Battersea Square itself. During the Saxon period, the Battersea Square area was part of the Manor of Battersea, in the possession of Caedwalla, King of Wessex (the West Saxons) from 685-688. The Manor was granted by him to Bishop Eorcenwold of the East Saxons for his sister Ethelburga’s Barking Abbey, and was recorded in a Charter of 13th June 693, confirmed by King Ethelred of Mercia.

Pottery fragments from c.800-1000 have been recovered from beam slots marking the foundations of a timber-framed building some eight metres long, and the remains of wattle-and-daub walling were also found during these excavations in 1976-7.

Battersea probably takes its name from “Baduric’s” or “Badric’s isle”, this area during the Saxon period characterized by a gravel and sand bank which was surrounded by marshy lowland, hence the term “isle”. The 1925 book Our Lady of Battersey gives 70 known spellings of the name occurring between 693 and 1597. “Battersea” was first used in 1595. The deposits of alluvium along the south bank of the Thames, around the site of St. Mary’s church provided fertile soils for market gardening, although there is speculation that there was a small fishing port centred on the church and Manor house during this period, with a landing point and timber buildings of the type described above.

Battersea was part of a large multiple estate also covering Wandsworth, Putney and stretching down to woodlands near Penge. The estate system was devised to encompass many different types of land in one holding, upland and lowland, with woodland, arable and pastureland to enable maximum exploitation of local variations, with provision for grazing, crops, reed harvesting (for thatching), fishing and a ready supply of building material.

The name of Battersea could also have come from “Patrick’s-eye,” a link to St. Patrick or St. Peter, as in 1067 William the Conqueror gave the Manor of Battersea to the Abbey of St. Peter at Westminster. It was referred to in the Domesday survey of 1086 as a Manor or agricultural estate, and was listed as containing a church, 7 mills, 45 villeins (tenant farmers), 16 bordars (smallholders), 14 ploughs, 8 slaves and 50 pigs. These totals would indicate a population of 300-320, and the mills alone were worth £42 9s 8d at this time, the most valuable in England as they served the growing London market.

Battersea's church was also referred to in the Domesday Book, and again in a papal bull of 1157, at which time the profits from the Rectory endowments were given by Pope Adrian IV to the Abbey for the founding of a dependent chapel in Wandsworth. The church has thus been a centre for worship for around a thousand years. It is not known if the earliest church was situated on the site of the present St. Mary’s, but there was certainly a church located there by 1301. Alterations were made to St. Mary’s in 1379, 1400, 1489, 1613 and 1639 before it was completely rebuilt in 1775-7. These alterations could be seen as having as much to do with the rising congregation as with the changes in worship. The medieval village is most likely to have occupied the same site as the Saxon settlement, with the present-day Battersea Square as its focal point, though there were shifts in the settlement pattern of the medieval period.

In 1225, during the tenure of the Abbey of Westminster, the manor was given over to the monks for their maintenance in bread and ale. This gave them rights over the income generated from the manor and its administration. This administration was achieved through local manorial officers, variously termed the Reeve, Sergeant or Bedell. The manor house was substantial by 1277-8, comprising the hall, a grange, hay barn, ox house, granary, dairy, dovecote, and pig house. There was probably also a cow house and stable, all most likely to have been of timber frame construction with daub or pargetting infill.

The Abbey retained direct control over the Manor until the 1390s, when the lands were leased out to the then Bedell, John Rydon, whose descendants held the lease until the Dissolution, by which time the existing medieval manor house had been demolished and rebuilt.

After the Dissolution of Westminster Abbey in 1540 the manor of Battersea belonged to the Crown and on 16th March 1627 the manor of “Batrichsey with Waynesworth” was sold to Sir Oliver St. John (a descendant of Lord Bolingbroke). The St. John family owned the land until 1763 when it was sold to Lord Spencer. The family manor house was built to the east of the church in the early 17th century. Nothing is known of the precise location of the medieval manor, although it was most likely to have been on the same site and may even have incorporated some of the plan form of the earlier house.

Battersea was by this point in its history a dynamic and sought-after location due to the rise in population and expansion of the city, and the manor house reflected this with its H-shaped design and large formal garden landscape to the north and east. When it was referred to in the will of Sir John St. John in 1645, the site, apart from the main house, included a haybarn, bakehouse, brewhouse, stables, barn, dovecote, outbuildings, and fishponds. From the 1670 hearth tax records, Sir Walter St. John was paying tax on 23 hearths, and the first floor of the main front elevation contained eight windows. The house was largely demolished in 1778 and became the site of the malt house and flour mill in the increasing industrialization of the area from the second quarter of the 19th century. The north wing, renamed Bolingbroke House, was incorporated into the mill site until the whole complex was demolished in the 1920s to make way for new mill buildings.

Until the late nineteenth century Battersea had been principally a market garden area, though the former agricultural land had been increasingly built upon from the Stuart era. Much of the area adjoining the River Thames was marshland and was not built upon. A marsh wall was built, and the land was reclaimed in 1560, though embankments may have been constructed as far back as the late Saxon period, such was the need to keep the marshlands well drained. Crops grown were largely carrots, melons, lavender, and asparagus. The asparagus grown in the area was renowned and became well-known as “Battersea bundles”.

Manufacturing industries in the locality also developed, in particular the brickmaking on nearby Latchmere Common. In 1638-9, 445,000 bricks were commissioned from Robert Taylor, 195,000 of these were used to rebuild the church tower at St. Mary’s. Most brick-built houses before 1800, of which a handful remain (notably Old Battersea House of 1699), were built from local materials.

Rocque's map of 1741 clearly shows the village of Battersea centred on Battersea Square. Battersea High Street, Battersea Church Street, Vicarage Crescent and Westbridge Road are also much in evidence. In 1700 the Sir Walter St. John School was founded on Battersea High Street, at the same time as Devonshire House in Vicarage Crescent appeared.

Fig. 1: John Rocque London in 1741-1745

In 1763 the manor was sold by the St. John family to Lord Spencer. He opened the isolated village by building a bridge across the River Thames in 1772. This led to the construction of several villas in the southern part of Battersea as residences for city merchants, the first time the village had been opened as an early commuter area for outsiders. The village was a small but thriving community. The Raven PH had been built around the middle of the seventeenth century and was used as a meeting place to discuss the rebuilding of St. Mary's church by Joseph Dixon in 1775-7. The vicarage (no. 42 Vicarage Crescent) was built in c.1800 and the 1838 tithe map lists the Rev. R. J. Eden as owning two large substantial garden plots as well as meadow land leading from Green Lane (now Vicarage Crescent), which is now Fred Wells Gardens. The church has always played a central and important part in the life of this corner of Battersea. J. M. W. Turner sat at the oriel window in the vestry to paint many of his cloud scenes, and the chair he used is displayed in the church.

The local workhouse for the poor was opened in Battersea Square in 1733, with one Jane Morland as its first “Misteris”, and the Square also housed the town stocks, mentioned in 1622. They were removed to near the church gate in 1811. The watch house was also situated in the Square, and local ne’er-do-wells were detained overnight there.

Fig. 2: OS Map 1869-1874

The Village remained largely isolated until the Victorian period when the construction of the railway (particularly from the 1860s with the building of Clapham Junction) encouraged the suburbanisation of London. Before this point, shops and services were scarce, with food produced locally or procured from street traders who moved around the district. There were thus few shops and only a few inns. Even in 1840, Battersea High Street had hardly any retailers. From a total of 168 shops in the whole Battersea area in 1852, 818 existed in 1871, an explosion which echoed the rampant housebuilding and population increase from the second half of the nineteenth century. The Village was taken over by this rapid growth, both industrial and residential. The population of Battersea increased from around 2,000 in 1690 to 5,540 by 1831, before the influx from suburbanisation boosted it to 168,905 in 1901, by which time it was a Metropolitan Borough. A railway station was built at Battersea High Street by 1863 for the West London Extension Railway, connecting Battersea with Fulham. The line went over the River Thames on a new bridge designed by William Baker, with the five 120ft spans of cast iron a testimony to the industrial developments of the nineteenth century.

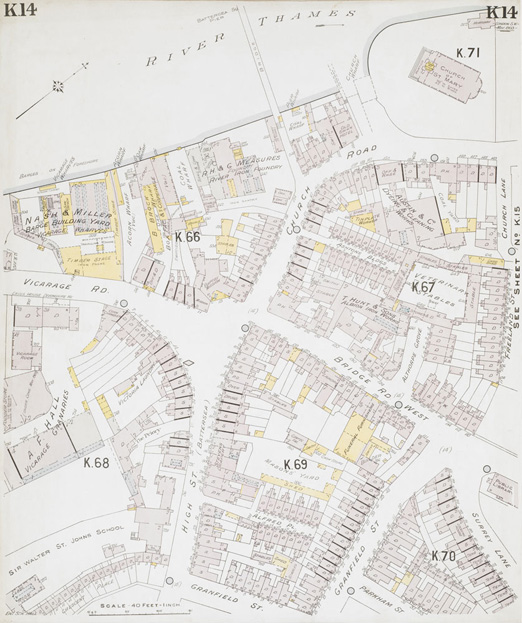

Fig. 3: Insurance Plan of London South West District Vol. K- sheet 14, 1903

The new road bridge designed by Sir Joseph Bazalgette in 1886-90 replaced the old wooden bridge across the Thames built in 1772 under the directions of Lord Spencer.

Fig. 4: Battersea High Street, the St John's Estate and Cremorne Bridge, Battersea, 1937

Battersea suffered badly from bombing during the Second World War, but Battersea Square area was not so badly affected. The main loss was Southlands College in the High Street, built for the Duchess of Angouleme during the French Revolution before becoming an educational institute. Post-war development was arguably more disastrous in this area, with the regrettable loss of the 17th century Castle Public House in 1962, symptomatic of the lack of conservation ethics existing at the time.

Fig. 5: Bomb Damage Map 1945

The Square itself was largely restored and enhanced following a long period of neglect and was completed in 1990. Today the Battersea Square area is predominantly residential, with a great array of pubs, bars and restaurants catering for its more leisure-oriented use.

Part Two: Conservation Area Appraisal

Location and Setting

Located on the east bank of the Thames, Battersea Square is just over 1km north of Clapham Junction Station and forms the core of the original village of Battersea. The medieval village was established around the Grade I Listed Church of St. Mary, which forms the northern extremity of the Conservation Area.

Topography

The village was founded on the low-lying marshlands within the floodplain of the River Thames. Through continued development, the level of the area has become regularised with no discernible gradient. The Thames Path to the west of the area, as in most of London, is raised from the riverbank.

Buildings and Townscape Overview

Battersea Square

The focus of the conservation area is Battersea Square, which has always been a triangle, and which retains much of its original street pattern and plot characteristics, with the vestiges of the old village around the Square. During the 20th century, the Square lost much of its identity when it was given over to traffic, including the name ‘Battersea Square’ falling out of common use and disappearing from mapping altogether. The main throughway, which feeds to the B305 Road, remains very busy and is a distracting feature from the intended tranquillity and pedestrian driven Square.

Fig. 6: The Square encourages activity such as al fresco dining and forms the heart of the Conservation Area

A scheme of preservation and enhancement was undertaken by Wandsworth Council in 1990 which sought to re-establish the ‘sense of place’ of the village by allowing part of the public space to be used by pedestrians, and by reviving the name Battersea Square – this includes the closing of through traffic from Battersea High Street, which instead goes around the Square, and there is a marked contrast between the two sides. The scheme involved introducing new paving using traditional materials and appropriate street furniture and using the public space for al fresco dining which brought much needed activity to the area. It received a Civic Trust Commendation in 1991.

The spire of St. Marys Church is visible from the Square, and this close relationship is an essential aspect in the character of the Conservation Area, underpinning the close historical associations and heightening the village character. The tight knit relationship between buildings and public spaces, and the pattern of the historical building plots, contrasts noticeably with more recent development, both adjacent to and within the Conservation Area.

Around the Square the building frontages were mainly two and three storeyed Victorian buildings, though many have been extended upward with setback mansard style extensions with dormers which has created a sense of homogeny to the scale of the area. Still, the buildings approaching and at the junction with Westbridge Road are slightly lower, which is more reflective of the original village form and creates a legible contrast to the slightly taller development to the south and along Battersea High Street.

Fig 7. Buildings typically extended to three storeys glimpsed through the trees

Fig. 8: Buildings have discreet roof extensions behind parapets and drop down in scale at the ends of groups

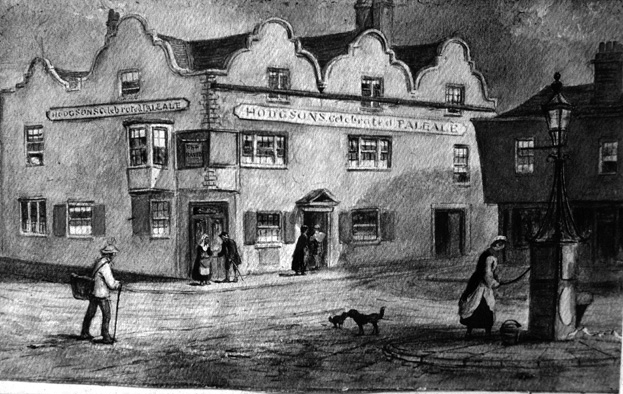

The Raven Inn public house (Grade II) is the most important surviving building within the Square and is the only building pre-dating the Victorian period. The building is datable on stylistic grounds to the later 17th century and was certainly in existence as the Black Raven by 1701 but has been subject to various alterations. Its Dutch gables and quoins create a pleasing contrast to the otherwise Victorian character of the Square and adds to its village character.

Fig 9: The Raven, Battersea Square 1868

Fig. 10: The Grade II listed Raven Public House is perhaps the oldest surviving building and sits at a prominent junction.

South of Westbridge Road, the buildings on the east side are largely the result of 19th century rebuilding, typical terraced with shopfronts to the ground floor, generally of a good quality.

The dominant building on the south side is Ship House, which is comprised of the former shop and offices of the granaries behind, dating from 1890–2 (No. 34), and the new granary dating from 1907 (No. 35). The stout group are 3-4 storeys with balanced elevations, turning the corner leading to Vicarage Crescent. Although stylistically different, shared materials heighten the impression of a pair, with stock brick construction with red brick detailing, as well as terra cotta embellishments. Windows are also smaller paned with metal frames, and No. 34 has an attractive shopfront dated 1892.

Fig. 11: Ship House

Fig. 12: Former shop and offices of the granaries, which partly survive to the rear

The granaries to the rear have been divided in their use, with No. 37 being residential in use and three storeys in height. No. 35 is the former Royal Academy of Dancing, a 4-storey 19th century warehouse with cast-iron windows which has been altered with its adaptation into the Academy, including a modern link to the adjacent two storey warehouse. The building is a surviving piece of the industrial architecture associated with uses that were originally dependent on a riverside location. With the vacating of the school, the warehouses are schedule for redevelopment, which should see an additional storey and conversion to residential use. The granite setts to the courtyard give visual interest to the setting of the building

Fig. 13: Former granaries, converted to residential use

Fig. 14: Former warehouse, converted for use as the former Royal Academy of Dancing, and now proposed to be residential

Fig. 15: Warehouse also formerly in use as part of the Royal Academy of Dance

Fig. 16: Courtyard with historic paving

Fig. 17 & 18: Detail of the stone setts

No. 32 adjoining is the oldest address on the south side but was probably rebuilt or re-fronted in the mid-19th century. Cotswold Mews to the east and south is a redevelopment of the former Cotswold Laundry - the now-remodelled building fronting the square dates from 1937, altered in the 1980s and again in 2011. A chimneystack in the courtyard rises above the 4-storey development and is visible in views throughout the area – an important marker of the industrial past of the village, particularly the works which extended to the south and west of the Square and highlights the importance river access had to the development of the area.

Fig. 19: No. 32 Battersea Square is probably the oldest address to the south side, though refronted or rebuilt

Fig: 20: The contemporary Cotswold Mews at centre repurposed a historic building and integrates well with the streetscape

West of this area is a curved terrace of five early 1880s buildings of 4 storeys including mansard type roofs. Originally these all would have had shops to the ground floor, which is evident on the Goad Map 1903, but all except No. 29 have been converted to residential, with surviving pilasters and corbels between the properties giving an indication of their original use.

Fig: 21: these terraces would have originally had shops to the ground floor

Fig: 22: The surviving shopfront of the group

The northwest group is anchored by a pleasant Victorian composition that neatly presents a public face to the square as well as turning the corner from Battersea Church Road to Vicarage Crescent. The right-angled configuration of Nos 7–9 is shown on Rocque’s map, but the present buildings are later. James Bennett, a linendraper, whose plaques for ‘London House’ decorate the front, was responsible for the diagonal infilling of the angle in 1866, closing a gateway to a yard and workshops beyond. No. 9 replicates No. 7 with its Georgian-style flat window heads and Italianate cornice, while 132 Battersea Church Road replicates the scale and proportions of No. 46, which may have been rebuilt around the same time as the corner infill, although it lacks its detailing.

Fig: 23: Nos. 7-9 are Locally Listed; No. 9 is a later construction to match the design of No. 7 (below)

Fig: 24: No. 7 (right) and an attractive terrace group

Fig: 25: Newer development matching the rhythm and scale of the corner buildings with contemporary shopfronts following historic design principles

The rest of the north side is occupied by a block of flats and commercial/offices at No. 1, a contemporary construction of 4-5 storeys which is broken into more palatable pieces through the use of recessed balconies. The ground floor treatment is flat and unattractive, lacking any detail or visual relief. The glazed sections are irregular, and given the use as private office space, the blinds are permanently drawn, creating an inactive street frontage. The west end is rendered which is unpleasant and uncharacteristic of the area, and the turning of the corner, while intended to mitigate the mass of the building, invites the eye to the car park beyond and unsightly Valiant House, and is not a view that needs to be emphasised.

Fig: 26: Contemporary residential development at No. 1 Battersea Square

Battersea Church Road

It is likely that a street in some form has led out of Battersea Square for at least a thousand years to provide access to the village church, presently the Grade I listed Church of St. Mary which was constructed between 1775 and 1777. The church forms the northern end of the Conservation Area, and the high walls and gates of its churchyard are historically dominant features of Battersea Church Road, though this significance as a landmark has been somewhat eroded by the dominating backdrop of the Montevetro building just to the north. Still, the mature planted yard and attractive spire are perched above surrounding development and form the terminating view out of the Conservation Area.

Fig: 27: St Mary’s Church, Grade I Listed

Development which addresses the road is primarily restricted to the east, with buildings to the west forming part of the riverside development as discussed above. While the building at the north end is historic, it is heavily modified, with the remainder of the terrace being more contemporary replacement buildings in a pastiche style. Even so, the townscape is consistent, typically four storeys with setback upper storeys, dropping down at the ends.

Fig: 28: Historic buildings survive at the end of the group, some much altered

Fig: 29: Later development follows historic proportions but has overly contemporary elements and colours

Buildings are typically two bays and materials of brick and render, much of which has been painted in bold colours which is uncharacteristic of the area. There are inset porches and an inconsistency in window treatments, with traditional sash windows to the historic buildings and plastic casement windows to newer constructions.

Roofs have been altered but are largely consistent in being clad mansards with modest metal dormers.

Westbridge Road

Fig: 30: The Coach House of Raven Public House

A short section of Westbridge Road is included in the Conservation Area, with two buildings surviving as remnants of the historic village, enduring the estate development that otherwise makes up the setting of the Character Area. No. 136 is a small two storey coach house, which would have served the adjacent listed public house and remains relatively unmodified apart from its rendering, but otherwise has an attractive brick frontage. There is also an attractive brick courtyard between them.

Fig: 31: Grade II Listed Royal Laundry

On the south side, Nos. 125-133 are the Grade II listed Royal Laundry, which date from circa 1725-50 with alterations of circa 1818-19. The group is comprised of a 3-storey house and flanking 2-storey cottages and is now stuccoed. Early to mid-19th Century shopfront fills the ground floor of each cottage, which are topped with a parapet with coping fronts mansard roof, with central flat-headed dormers.

Battersea High Street

Fig: 32 & 33: The former Sir Walter St. John’s School, Grade II listed

At the transition from Battersea Square to Battersea High Street is the former Sir Walter St. John's School of 1858-59 by Butterfield (Grade II), with its later extensions. Overall, the building is consistent in its 3-storey scale and red brick construction, with less detailing to its later sections, but has a slightly overbearing presence.

Further south is a collection of modest heterogeneous buildings symptomatic of the area’s long history and fragmented ownership. The earliest surviving fabric is no earlier than Victorian, and some is more recent period pastiche. Buildings are typical two bay wide terraces with multiple interventions, including various roof forms. There are two attractive pubs, No. 60 & Nos. 42-44, which are composite buildings of earlier construction with later expansion and addition, which add visual interest and draw the village character southward. Other buildings have simple, balanced elevations, with typical modest detailing, and are most often constructed of brick, though many front elevations and architectural embellishments have been rendered or painted white. While most buildings front the street directly, a small group to the south of the school have simple iron rails enclosing front paving. A group of these also have bars to ground floor windows which creates an unwelcoming appearance. Inset porches and projecting bay windows add visual interest and help break up an otherwise flat streetscape.

Fig: 34: Nos. 42-44

Fig: 35: The Locally Listed 60 Battersea High Street

Fig: 36: Homogenous groups of short terraces

On the east side of the Street, the area expands to include the Roman Catholic Church of the Sacred Heart (Grade II) of 1892 by F. A. Walters, constructed in the late Norman style. Otherwise, the east side has largely been redeveloped with local authority housing of the 1950's that contrasts with the established pattern of development, and while not forming part of the Conservation Area, largely forms its setting.

Fig: 37: A slightly taller typology to Battersea High Street

Fig: 38: Grade II Listed Church of the Sacred Heart

Although largely concealed from the area, Restoration Square is a private development of c.2000 set behind the High Street frontage between the Woodman and Powrie House. It partly utilises the former St John’s cigar factory of 1875–8, though the L-shaped factory building was largely demolished, leaving most of the north wing. The complex was reconstructed to a slightly larger scale. In the courtyard, three ‘mews’ houses were built, while along the High Street, the buildings were variously refurbished or replaced with houses in broadly neo-Georgian style. A gap in the frontage rounds the corner at Powrie House, which is set back with a low brick boundary, described in further detail within the ‘Vicarage Crescent’ section.

Fig: 39: Entrance to Restoration Square, a contemporary development beyond, incorporates pastiche Georgian buildings

Fig: 40: Access to development behind breaks up the streetscape

Fig: 41: Pair of cottages restored / rebuilt as part of the development of Restoration Square

South of Vicarage Crescent is a consistent terrace group of three storeys, some with dormers in mansard fourth storeys. The tall, plain houses at Nos 88 and 90 are the remnant of a development of the mid-to-late 1840s, and an adjacent pair were largely reconstructed in a sympathetic style, though are not as interesting. The bookend to the group is Nos. 104 and 106, which date from the mid-1880s and are, instead, of a red brick construction with greater variation and detail in their design, with No. 106 turning to address the corner. The different brick to ground floor suggests reconstruction, likely infilling a shop. Between the historic houses is a set of infill houses/flats which respect the materiality and have symmetrical elevations but make extensive use of unsympathetic uPVC casement windows and are ultimately of little architectural interest.

Fig: 42: The taller group to the south of Battersea High Street is bookended by an attractive pair of townhouses

Fig: 43: The opposite side has a more detailed pair in red brick

Fig: 44: The middle section has been infilled with an overly simplistic housing design which has poor quality windows

Fig: 45: Detail of the irregularly sized and spaced windows with uncharacteristic casements

At the south end of the High Street is the 18th century Katherine Low Settlement (Grade II), formerly called The Cedars, the only survivor of several large houses in the southern part of the High Street. The large symmetrical house dates from the early 18th century and is 3-storeys in brown brick with stone dressings, with a similar single-storey extension with frontage to the street. The large corner building forms part of the settlement but is a 20th century construction in red brick with green tile to the ground floor.

Fig: 46: A later building which forms part of the Katherine Low Settlement

Fig: 47: The Grade II Listed Katherine Low Settlement

On the east side of the High Street at Shuttleworth Road are two larger developments – to the south is the Old Library Apartments, housed within the former library of Southlands Training College, later South Thames College. The large building is out of scale with its surroundings but is a remnant of a robust college, which would have rivalled the Sir Walter St. John's School and formed an attractive bookend to the High Street. The surviving fragment is well preserved with much historic fabric and a relatively sensitive conversion. To the north of Shuttleworth is a contemporary flat building. While the building is also 4 storeys in line with surrounding development, there are few other similarities. Its scale is disproportionate, sitting on a tall ground floor pediment, and having a taller height and greater massing overall. The materials are glazed brown bricks and lighter brown brick mixed above, which lack context. The projecting elements, and window size, placement, and proportion, are inappropriate to the existing streetscape and general appearance of the area.

Fig: 48: Former library converted to residential use

Fig: 49: A more contemporary development which does not obviously respond to its context

Vicarage Crescent

Fig: 50: Grade II* Devonshire House and Grade II St Mary’s Vicarage

Vicarage Crescent wraps around the west half of the Conservation Area and has a varying townscape, which can be divided into three sections. At the transitional point from the Square, the south side of the street is characterised by robust historic buildings, including Devonshire House (Grade II*) and St. Mary's Vicarage (grade II, and Old Battersea House (Grade II*), which have been converted to office or retain private residential use. The group ranges from 2-4 storeys, with upper storeys being set back hipped or mansard style roofs with dormers. The buildings are characterised by their attractive brick construction (Devonshire House is rendered but has exposed brick elements), symmetrical composition, and traditional sash windows. The mature gardens, rails, and gates (which are also listed), form an important element of the streetscape, contrasting with the commercial character central to the village square.

Fig: 51: No. 34 forms part of the group of buildings to the north of Vicarage Crescent with robust buildings set in shallow front gardens

Fig: 52: Grade II* Old Battersea House

The west side of the Crescent is characterised by contrasting block flat development while the curve is characterised by the St Johns Estate, both of which are addressed in further detail below.

The east end of the Crescent connects to Battersea High Street and transitions to a more similar character at the approach to Orville Road. Just west of Orville Road is the Grade II St Mary's Church of England Primary School, a symmetrical 2-storey building in the form of a pair of houses, the whole 6 bays wide of yellow stock brick with hipped slate roof.

Fig: 53: Grade II Listed St Mary's Church of England Primary School

A pair of matching three storey terraces flank Orville Road, constructed of stock brick with red brick and render dressings. They have been heavily modified with rear dormers disrupting their symmetry, and unsympathetic windows throughout.

Fig: 54: One of a pair of short terraces – the insertion of casement windows has altered the appearance of the group

On the north side, a short terrace transitions to the scale of the High Street, typically two storeys, though some London roofs have been extended. There is little consistency to the group, which has been heavily altered from the original mirrored pairs they would have been, remnants of which survive on the west end. The façades have been painted or rendered and the group is peppered with varying window types and treatments to the detriment of their character. A carriageway leads to contemporary development behind.

Fig: 55 & 56: This altered terrace conceals contemporary development to the north

At the corner is the first Council housing on the High Street at Powrie House. This was built in 1958–9 by Prestige & Company, probably to the designs of Howes & Jackman. It is a plain, flat-roofed, 4-storey block, with Royal Festival Hall-style concrete balconies.

Fig: 57: Powrie House

St Johns Estate

Fig: 58: Winfield House, one of the smaller buildings on the estate with a slightly different design

Built in 1931–4 on the site of the former St John’s Training College, this estate represents Battersea Borough Council’s main inter-war housing effort. Old Battersea House, which survives to the northwest along Vicarage Crescent, was originally where the principal of the college lived, and the original intension was to demolish the building and use the land as part of the estate. When this was resisted, the Council was forced to redesign the site within a smaller footprint, and the resultant layout is more compactly planned with blocks that somewhat overwhelm Old Battersea House. The estate is comprised of five 5-storey blocks positioned in as symmetrical a layout as was possible within the irregular site.

Fig: 59: White House

Fig: 60: Views toward landscaped courtyard at White House

The smaller blocks of Winfield House and Eaton House were built first, from 1931, while the more monumental central group followed on from 1932. It consisted of the quadrangular Archer House and White House, linked together by the narrow Haythorn House to form two tight internal courts with an open court between (intended to be a playground but currently used as a car park).

Reflecting the owners of the scheme, the architectural language of the estate follows that devised by the LCC for its walk-up flats of the 1920s, but with longer elevations than typical. Some extra flourishes were no doubt added by the architect who drew up the detailed designs. The massing is good, and the entrances to Vicarage Crescent are effective, with attractive oriel elements and large arched rendered openings with ornate gates, though which attractive landscaped courtyards are visible. On the show fronts, regular four-storey elevations of yellow brick with timber sash windows rise to the cornice. The fifth storey is mostly embedded in the mansard roof, as originally imagined, but brought forward and squared off in the projecting central features. The western block differs slightly in that they have red brick dressings largely limited to brick courses and quoining to corners, while the east block has red brick window surrounds giving a stronger vertical emphasis.

Fig: 61: The south elevation of Winfield House showing vertical emphasis and redbrick detailing

Fig: 62: Archer House

With the bulk and scale of the buildings and their spacing, as well as large, landscaped grounds, the estate dominates the corner of the area, and imposes itself on the experience of travelling through along Vicarage Crescent. Despite its massing, the verdant gardens break up its appearance and contribute to an attractive village character, which continues northward, and is reflective of the layout of the robust listed buildings leading into the Square.

River Frontage

Fig: 63: View from the Thames Path toward St Mary’s showing the taller building development which characterises the area

West of Battersea Church Road, Battersea Square, and the beginnings of Vicarage Crescent, the frontage to the River Thames is characterised by blocks of flats built in the 1970's. Their layout, form, and scale contrast decidedly with the character and appearance of the rest of the c area, paying little regard to the prevailing pattern of development, including plot sizes and address to public spaces. A public riverside walkway, which is part of the development, continues through into the riverside public space beyond.

The central pair, which includes Valiant House, was begun in 1971 and led the way in utilizing the potential for waterside apartments along the Thames and elsewhere. The buildings are 6-8 storeys in height, and their expanses of dull brown brick seem understated. Projecting elements have roughcast panels and provide flats with either a bay or balcony, and there are a small number of roof terraces. Windows are a mixture of sash and casement in matching brown framing. As the central pair, views toward the buildings are limited by the development to Battersea Square, and the mature planting and climbing ivy helps mitigate their appearance in warmer months.

South of the pair is a former Wandsworth Council social-housing scheme which was built on land previously forming Vicarage Wharf. The Riverains were built from 1973–4 to a design by Jefferson Sheard & Partners. The blocks step down from 6 to 3 storeys, but despite their smaller scale, take up a similar space. Similarly, the blocks are clad in brown brick to harmonize with Valiant House, with slate infill panels. There are projecting bays to the river frontage and windows are white casements, which contrast sharply with the otherwise dark colour palette.

Fig: 64: The Riverains

North of Valiant House, the flats occupying the former Old Swan Wharf at 116 Battersea Church Road were built about 1995 to designs by Michael Squire Associates. The 5-storey building has inset upper storeys, which at least attempt to manage its bulk, with numerous balconies surrounding. The finish to three sides is white render, which in combination with the balconies and extensive sliding panel windows/doors gives the impression of a resort building, and entirely lacks context. The east façade has a bizarre contrast in buff brick with awkwardly small windows, which is clearly an attempt to be more in character with the appearance of the village centre, but the execution is not successful, and the façade is rather imposing.

Fig: 65: Old Swan Wharf

Fig: 66: East elevation of Old Swan Wharf

The River Thames frontage itself is also important. From the quay around the slipway adjacent to St Mary’s Church extensive views up and down the River Thames can be obtained, and there is a pleasant promenade at Vicarage Crescent allowing for pedestrians to stop and enjoy extensive views or access the Thames Path. At the extreme ends of the frontage boundary there are a number of moored barges which are equally pleasing, and along with the slipway, add a charming maritime character, creating a loose link to the formerly central aspect of the wharfs, which once lined the Thames.

Fig: 67: View south toward Cremorn Bridge

Fig: 68: Vicarage Gardens

Fig: 69: View of the river frontage with moored barges and Vicarage Gardens

Fig: 70: View from the riverbank with flat development showing character of the river frontage.

Spatial Analysis

Fig: 71: View south from the Square towards Battersea High Street. The sense of enclosure is mitigated by the slight curve and sky visible beyond

Though there is a consistent building line and height giving the impression of enclosure, the landscaping, lively character, and arterial views out of the Square mean the experience is rather unconfined. Instead, there is the impression of definable neighbourhood or pocket of a village, offering a respite from the homogenous character of surrounding estate developments. This village character is heightened by the glimpsed view of the church spire, and views toward taller building developments both break and enhance the illusion. The curved arterial roads both invite into the Square and encourage exploration of its peripheries. The presence of traffic erodes the experience and is a distraction to all senses, being uncharacteristically noisy at rush hour periods, smog from idling vehicles, as well as creating a visual and physical barrier. Although there are a few surviving remnants of industry, which once flourished in the area, a clear connection to the river is not immediately obvious from within the Square itself.

Fig: 72: View of St Mary’s spire from the Square

Travelling north of the Square toward the Church, the tightly woven development and slight curve of the road creates a more obvious sense of enclosure, drawing the eye to the end of the street and the spire of the church, which remains blocked from view until reaching the end of the village, making the reveal more significant and making a lasting impression. The church would have been the most prominent building, set in its own grounds to prevent development from overbearing, but the contemporary tall buildings beyond have eroded this view and experience. Equally the enclosure and glimpsed views travelling into the Conservation Area from the church remain inviting.

Fig: 73: The church is revealed at the end of the curve of Battersea Church Road

Vicarage Crescent has a more open character and experience, with larger buildings set within much larger grounds, and a more verdant character. While the blocks of flats impede views toward the river, their grounds, mature planting, and set back from the road contribute to the overall openness.

Fig: 74: The greenery of Valiant House softens its appearance, but the placement and scale of the buildings prohibits experiencing the Thames beyond

Fig: 75: Vicarage Gardens is one of the main green/open spaces in the Area and opens access to the Thames

Longer views are possible toward the river through Vicarage Gardens, with Cremorne Railway Bridge visible beyond. Vicarage Gardens was created around the beginning of the 20th century when Vicarage Crescent was extended to link to Lombard Road to the south and provides a pleasant promenade to the river affording views up and down the River Thames. Though St Johns Estate is monumental in scale, its set back, mature boundary hedge and layout, break up the massing and allow for views into the Estate itself. In tandem with Fred Wells Gardens to the south, outside of the Conservation Area, the area has a completely contrasting feel to the urban square.

Fig: 76: Though St Johns Estate is rather monumental in its scale, its breaking up into sections and robust planting mitigates this appearance

Battersea High Street and the east end of Vicarage Crescent have a shared spatial structure, both having a mix of more dense historic terraces and later interventions which tend to be detached or set back from the street. Despite most development fronting the street directly, there are numerous access roads which lead to back land development, breaking up development into legible terraced groups. Later estate development, while primarily outside of the Conservation Area, have nevertheless had a significant impact on the spatial character of the area, being large consistent blocks, to a greater scale and massing, but perhaps more significantly, set back from the road with front gardens. These have completely shifted the character of the original High Street from a restrained linear development, exposing the surviving western string of development.

Fig: 77: Although outside the Conservation Area, the setting back of estate buildings has opened up Battersea High Street

Architecture

The evolutionary character of town centres, shifting to reflect the needs of its occupants, results in a complexity of urban development and variations in their overall character. While this is expressed to a smaller scale and degree within a small village centre, its importance to a local community, long history, and fragmented development, means there is still a wide variation in surviving fabric, building typologies, and other townscape features, which have been outlined in more specific detail above. While this document carries out a general street analysis where a more obvious or linear approach to character and appearance is legible, there is a commonality in styles, materials, and features, which are evident and relatively consistent throughout the Conservation Area to be further addressed. Given the variety of the area, the descriptions are not exhaustive.

Commercial and Shopfronts – Commercial premises and historic shopfronts are predominantly within terraced groups and surround the Square, with a shopfront to ground floor and residential (increasingly mixed-use) above. Shopfronts are most often well maintained with good examples of surviving historic shopfronts and high-quality modern insertions, though there are a few examples of overly modern shops which are uncharacteristic of the area. Different colour shopfronts can add variety and richness to the area, and identify a particular shop, without altering the external appearance of the host building itself.

Fig: 78: The historic elements of this shopfront are incorporated well into its design

Fig: 79: Pastel colours add vibrancy and visual interest without being overbearing

Fig: 80: Modern pastiche shopfronts which have been informed by historic designs integrate well into the streetscape

Fig: 81: Individual elements such as security bars and contemporary signage can easily detract from otherwise attractive shopfronts

Windows make a substantial contribution to the appearance of an individual building and can enhance or interrupt the unity of a terrace or semi-detached pair of houses. The Conservation Area contains a wide variety of window styles, typically of a good standard, but with a number of unsympathetic replacements outside of the Square. It is important that a single pattern of glazing bars should be retained within any uniform composition. Generally, windows follow standard patterns/styles. In Georgian and early-mid Victorian terraces, each half of the sash was usually wider than it was high, but its division into six or more panes emphasised the window opening’s vertical proportions. Later Victorian and Edwardian buildings often employed a simpler pattern, with the top and bottom sash either having one large pane, or a single central glazing bar. Windows reduce in size and have simpler surrounds as they rise through the building demonstrating the hierarchy of internal spaces.

Window frames are most commonly white painted timber, and where uPVC replacements have been inserted, these are mostly white and reflect the historic glazing pattern. Casement windows are uncommon, and predominantly are a result of later, unsympathetic interventions.

Fig: 82: These windows are irregular placed and fail to respond to surrounding context. The use of casement windows is also uncharacteristic of the Area.

Fig: 83: The windows in this group are better preserved but the casement windows to bottom right illustrate how inappropriate replacements can impact entire elevations and groups.

External Finishes - Bricks are the most common building material within the Conservation Area, primarily stock and yellow brick with a minority of red brick, which is otherwise common for embellishment. Rendering is often restricted to the ground floor, but has become increasingly common to entire façades, almost exclusively in neutral white. Some painting has occurred, which is also predominately white, but remains uncharacteristic. Recent painting has occurred in bright colours, which is deeply uncharacteristic of the area and should be avoided.

Contemporary development has also employed brick skins to various degrees, generally in a pastiche or sympathetic design, utilising colours from the general palette of their immediate settings.

Fig: 84: Overly contemporary intervention can overpower surviving historic fragments and well proportioned contemporary development

Roofs are most commonly finished in black slate and roof extensions have been carried out extensively, with few original roof forms surviving. Most extensions are a simple mansard style, inset from the parapet with flat metal clad dormers. As most buildings have already been extended upward, additional vertical extensions are inappropriate and would create a scale beyond the intention or capacity of the host buildings. Where original roofs do survive, there is variation in their form, but most often simple pitched or hipped roofs in terrace groups. There are a small number of London roofs in red tile which survive.

Residential – Street facing residential buildings are predominantly Victorian or Victorian pastiche, generally in good order but with various levels of intervention. The houses are typically terraced and 2-3 storeys.

Contemporary housing is primarily provided in flats which have generally repurposed and/or extended historic buildings or combined with modern buildings. These developments are typically concealed by dense street frontages and extend up to 4 storeys.

Open Space, Gardens, and Trees

Fig: 85. The churchyard is one of the few greenspaces and its mature planting and benches attract residents to spend time in the grounds

Vicarage Gardens and the churchyard of St. Mary's are the primary areas of public open space, but semi-private spaces and private gardens, where they do exist, are often well planted, and add to the area's character. Fred Wells Gardens adjoins the southern boundary of the area.

Fig: 86: Vicarage Gardens

Few street trees exist, although some semi-mature trees were reintroduced in the enhancement scheme for the Square. Originally these would have been elm trees but are now the more suitably scaled Raywood Ash.

Fig: 87: Street trees are primary found in the Square

Paving

Paving varies throughout the area but is typically of a very good quality. The peripheral roads to the Square are most often a combination of square York stone pavers in various shades, transitioning to purple brick in various bonds, particularly to Vicarage Crescent, where there is a mix of a houndstooth bond and basket weave, but predominantly a simple running bond. Kerbs are high quality granite.

Fig: 88: Pavers to the Battersea High Street

Fig: 89: Bricks in a herringbone pattern are common to pavements

Dotted along Battersea Church Road and the north end of Vicarage Crescent, notably adjacent to St. Mary’s, Old Swan Wharf, and the group of listed buildings, are areas of historic stone setts. These are remanets of much earlier development, when the riverfront was more industrial in nature, and make a very attractive contribution to the character and streetscape of the area.

Fig: 90: Historic stone setts adjacent to Old Swan Wharf

Fig: 91: Detail of setts next to St. Mary’s

Fig: 92: Stone setts to the entrance to Eaton House

The Square itself underwent an extensive revitalisation in 1990 which created a new floorscape using traditional materials, including York stone pavers and granite setts.

Fig: 93: Pavers in the Square

Fig: 94: Stone setts in the Square

Street Furniture

Street furniture is predominantly located in the Square itself and formed part of the extensive refurbishment/refresh scheme in 1990.

Bollards

Decorative black bollards line the square itself as well as the ends of the peripheral roads, which helps guide traffic through and provide a visual separation between pedestrian space and the road. The private road to Eaton House has white bollards with black caps

Simple timber bollards serve a similar purpose to Battersea Church Road, the southwest curve of Vicarage Crescent, as well as the junction with Battersea High Street.

Figs: 95-98: Various bollards in the Area

Streetlights

Streetlights to the Square are black with ornate posts, either vertical or with a short overhang. Outside of the square, posts are a standard grey and are modern LED lamps. Along the riverfront, posts are grey with a pair of orb lights, and while unassuming, are consistent with a lighting pattern which extends beyond the confines of the Conservation Area.

Figs: 99 & 100: There are two styles of ornate lampposts found in the Square

Benches

A number of timber and cast-iron benches were introduced as part of the restoration of the Square in two designs, essentially a more traditional bench, and a flat seat with no back. The benches encourage active use of the Square and contribute to its liveliness.

Post Boxes

Outside Ship House is an uncommon replica hexagonal Penfold pillar post box with VR cipher paired with a modern cuboid parcel box. A standard pillar box is located across from the preparatory school at the entrance to a pedestrian footpath.

Fig: 101: Post box with VR cipher

Cycle Parking

There is a good amount of cycle parking to the square in the form of simple black Sheffield bike stands, but otherwise lacks throughout the rest of the area. There is a Santander Cycle dock at the southwest corner of Vicarage Crescent.

Fig: 102: Cycle parking is well provided in the square but there is little elsewhere

Bins

Style of bins are inconsistent, with round, square, and rectangular all present. They share a colour palette, however, of black bins with gold banding and lettering.

Fig: 103: Typical refuse bin

Part Three: Management Strategy

Summary

The Appraisal has assessed the quality and the condition of the Battersea Square Conservation Area. Site visits were undertaken between June and July 2022, when the area was observed and photographed.

This Appraisal has summarised the strengths and weaknesses of the area and this management plan will set out a strategy to consolidate and enhance these strengths and prevent further erosion of the area’s special historic and architectural character and appearance.

The overall conclusion of the Appraisal is that, despite piecemeal erosion, all areas of the Conservation Area are worthy of inclusion. It is hoped that this clearer, more extensively illustrated Appraisal will assist the Development Management process in making more informed planning decisions in respect of the area’s character. It will also assist applicants to ensure their proposals contribute positively to the conservation or enhancement of the Conservation Area.

Under section 71 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 local planning authorities have a statutory duty to draw up and publish proposals for the preservation and enhancement of Conservation Areas in their area from time to time. Regularly reviewed appraisals, or shorter condition surveys, identifying threats and opportunities, can be developed into a management plan that is specific to the area’s needs.

Proposed Boundary Change

During the appraisal process, it was also determined that the boundary of the current Conservation Area should be amended, with an expansion to include the St. John’s Estate and its grounds, located to the south of Battersea Square, and which the current boundary surrounds. This would, include Eaton House, Archer House, Haythorn House, White House, and Winfield House.

Design Guidance

Historic England recommends that the Appraisal is a source of guidance for applicants seeking to make changes that require planning permission, helping to make successful applications.

The guidance below will set out design guidance which encourages good quality of design, which will help to both preserve and enhance the Conservation Area. Dwellings within the Conservation Area, which are blocks of flats, do not benefit from Permitted Development Rights, requiring planning permission to carry out alterations and extensions.

Traffic

Traffic is an issue for the public realm within the Conservation Area and any opportunity to reduce the flow of through traffic within the centre to make it a pedestrian and cycle friendly place would be beneficial to its character and appearance.

Windows

Windows make a substantial contribution to the appearance of an individual building and can enhance or interrupt the unity of a terrace, so it is important that a single pattern of glazing bars should be retained within any uniform composition. Generally, windows follow standard patterns/styles. In Georgian and early-mid Victorian terraces, each half of the sash was usually wider than it was high, but its division into six or more panes emphasised the window’s vertical proportions. Later Victorian and Edwardian buildings often employed a simpler pattern, with the top and bottom sash either having one large pane, or a single central glazing bar.

Many original timber sliding sash windows survive within parts of the Conservation Area and these make an important contribution to the special character and appearance. However, some have been lost and many replacements are of a different style and materiality which is unsympathetic to the historic appearance of the building and Conservation Area, disrupting the harmony and rhythm of the legible groups, and creating inconsistences within the otherwise congruous terrace typologies.

The quality of these replacements also varies, which dilutes the consistent appearance of the building groups, with some mimicking historic style while others are inappropriate uPVC and casement windows. Where timber sashes have been replaced, these are often of poor quality, with thicker frames and higher reflectiveness, varied horn details, a variety of glazing bar formats, and there is a general lack of consistency to the approach to fenestration. Other inappropriate interventions include the widening of windows and introduction of large bow and bay windows, which creates visual disparity to the otherwise consistent scale and appearance.

It is encouraged that residents, in the first instance, retain and repair existing original timber sash windows. If replacement is required, all aspects of the window should be considered including opening type, glazing bar pattern, horns to sashes, and depth. Windows should be timber sash and are generally single panes with no glazing bars or a simple two-over-two. Timber frames are not only the most appropriate option, but a natural material which helps reduce the use of plastics, often found in other windows. Timber windows also have the benefit of being more cost effective, being much more durable and repairable than alternatives, and there are options to maintain their appearance while introducing energy saving and noise reducing features.

Single glazing is perhaps the most common window type. As such, simple like-for-like replacements would likely cause the least harmful impact on the existing appearance of a building and therefore the character and appearance of the area. Like-for-like replacements also benefit from being able to be carried out without the need for planning permission. Existing windows can often be improved through secondary glazing, where an additional glass layer is installed behind an existing window. Secondary glazing is an unobtrusive option to increase efficiency, reduce noise, and avoid intervention to existing fabric, often performing as well, and lasting longer than double glazing. This approach also often benefits from not needing planning permission.

Where appropriate and where there is justification for full replacement, slimline double and triple glazing with timber frames helps maintain a consistent appearance, while offering similar benefits to secondary glazing. Where double/triple glazing is accepted, black spacing bars and seals should be avoided – these should instead be white to blend with the frame. Trickle vents should be avoided or well concealed within the frame to maintain consistency with historic appearance.

Windows to contemporary development can vary in detail but it is still important to consider their design in relation to the character of the area.

Shopfronts and Signage

The quality of shopfronts within the area is relatively strong, with only a few examples of low-quality modern shopfronts inserted. Where historic elements survive, these should be retained and repaired in the first instance. Where traditional forms have been replicated or contemporary shopfronts inserted, these should continue to follow traditional designs should they need to be altered or replaced. Any new or replacement shopfronts proposed will need to maintain or improve the appearance of the existing shopfront or also follow these traditional designs as outlined by policies in the Local Plan, as well as the, the Adopted ‘Shopfronts’ Supplementary Planning Guidance (1988)

Signage should replicate traditional styles with painted or applied letters to the fascia and simple hanging signs. Modern signage, including corporate branding, internally illuminated projecting box signs, and plastic / box fascia signs, will be resisted. Projecting signs should be of an appropriate scale and design, attached to the fascia or to the building in an unobtrusive manner. Where hanging signs are employed, these should use a traditional bracket and be of a simple design, as outlined in the shopfront SPG.

Shopfront Security

Shopfront security can have an imposing impact on the appearance of the streetscape and create an uninviting atmosphere. Projecting shutter boxes have a negative impact on the appearance of shopfronts and are not acceptable in conservation areas, nor are solid or perforated shutters. Unless they are continuously back-lit, the perforation is only really apparent directly in front of the shopfront itself – from other angles and from further away they seem solid, and solid shutters create an unwelcoming, unattractive environment. By blocking the interior, they also prohibit passive surveillance and are more likely to be graffitied, which would cause further harm to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area.

Instead, there are other systems, which would be more suitable, and these are outlined in both the Shopfronts SPG, and the unadopted Security for shops: Design Guidelines.

For contemporary shopfronts, more passive security measures can be effective, such as laminated glass, which is not readily apparent and therefore mitigates detracting from the appearance of the shopfront. Lattice brick-bond grilles can be installed internally behind the windows, with the box inserted into the ceiling – this prevents an external projecting box and the internal box from being visible through the shop window. This would allow for an appropriate level of security, while minimising the visual impact of shutters on the external appearance of the shopfront, and therefore on the Conservation Area. It also allows for passive observation by keeping the inside of the shop visible.

Doors

Like windows, it is encouraged that residents, in the first instance, retain and repair any existing original timber doors. This is best for the environment, for the character and appearance of the area, and is often a more inexpensive solution to complete replacement. Simple modifications can often be carried out internally which improves the weatherproofing of the door without impacting its external appearance.

If a replacement is required, then it should match the original door for the property. Doors are typically simple timber four panel doors to Victorian buildings.

Existing styles of doors in the area generally manage to reflect the architectural style in which they are set, and original examples make a great contribution to the character of the area.

There is a prevalence of door furniture within the Conservation Area, such as decorative door knockers, letter flaps, and doorknobs, which add interest.

Roof Extensions

Roof extensions within the Conservation Area are not uncommon and have generally been restricted to a single storey. This consistency in scale and style (typically mansards) has allowed for the existing scale and variation in buildings heights to remain coherent. Buildings generally have a slightly taller average height to the Square, scaling down at the peripheries. The exceptions are taller blocks of flats, which are restricted to back land development, the riverfront development, and St Johns Estate.

Materials are key to incorporating new elements into existing buildings, and a sympathetic approach should also be considered first. For mansard extensions, slate and lead cladding is often the most appropriate and least visually intrusive. Where a more contemporary approach is pursued, this must be of an extremely high quality, and still within the parameters outlined above.

Roof terraces are also increasingly common, and where allowed, should use materials which do not interrupt or add volume to roofs, and be set back sufficiently so as to not be visible from the street.

Gardens and Greenspace

Gardens are uncommon and primarily restricted to private amenity space to larger flat developments or the grounds of the group of listed buildings and estates. Most of the greenery to the Square comes from street trees and seasonal planters.

Planting can soften the appearance of the continuous frontage and heighten a village feel, where full hard landscaping creates uninviting frontages and should be avoided. Parking within gardens is similarly harmful to the character and appearance and will be resisted.

Boundaries

Boundary walls or other markers are uncommon to the Conservation Area as most properties front directly onto the street or Square, though there are limited examples along Vicarage Crescent, where the concentration of residential houses is.

The listed group to the west of the Area typically has robust brick walls, some solid and others with rails above, which are frequently combined with mature planting and hedges. While this creates a sense of privacy and separation to the street scene, it also contributes to a green village character and breaks up the extensive brick.

Rounding the corner, St Johns Estate employs a mature hedge in combination with brick piers and ornate metal gates to access points. This defines the boundary of the estate and makes a positive contribution to its character and appearance, while also providing privacy, security, and a verdant appearance.

At the eastern end of the Crescent, boundary treatments vary a mix of brick, render, railings, or a combination. This inconsistency and loss of historic boundaries is unattractive and detracts from the appearance of the residential group. Restoration of some level of harmony would greatly benefit the appearance of the streetscape more generally, and thus the character and appearance of the Conservation Area.

Typically, a contrast between the host building and boundary treatment is undesirable and can create undesirable interruptions to otherwise consistent boundary lines.

Lightwells

Lightwells can be discreetly inserted where garden space allows and should follow best practice outlined in the Housing SPD (2016) as well as policies in the Local Plan. Where lightwells are accepted, they should not be paired with full hard landscaping, but rather mitigated with soft landscaping elements, such as low maintenance shrubbery.

Painting and External Finishes

Painting is uncommon and should only occur if the existing location has already been painted, and an appropriate colour should be selected to maintain the overall neutral palette of the Conservation Area, excluding shopfronts. Most often existing colours should be refreshed, or neighbouring houses can be referenced to create a harmonious appearance.

External finishes are not a common feature to the Conservation Area as a whole, and the approach to their treatment is similar to paint – where existing finishes can be repaired and restored, and new finishes not normally approved. The predominant character of the area is derived from the consistent use of brick with some details and dressings in white and red. Where full or part smooth render has been carried out, it has harmed the architectural coherence of the terraced groups and creates a visual disruption.

Energy Efficiency

Introducing energy efficient measures can be desirable to reduce carbon emissions, fuel bills, and improve comfort levels. It is important that the appropriate course taken should be informed by the context of the building being improved, with each building having different opportunities and restrictions. Not all solutions will be appropriate across the Conservation Area, and the ‘Whole Building Approach’ advocated by Historic England encourages a case-by-case approach, which fundamentally considers the context, construction, and condition of a building to determine which solutions would be the most suitable and effective. More detailed advice can be found within the Guidance Note Energy Efficiency and Historic Buildings: How to Improve Energy Efficiency 2018.

Solar Panels

Solar Panels and equivalent technology are most suitably placed on rear or side elevations where they are hidden from the public realm – principal elevations and roof slopes facing the public realm are less appropriate as they generally make the most substantial contribution to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area. New technologies, such as PV panels disguised as slates and sitting flush with roof materials, may be suitable in the appropriate context, and will be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Appendix: Locally Listed Buildings

Postbox Battersea Square – replica – Hexagonal pillar post box with VR cipher. Only a minority of post boxes in the UK carry this cipher.

"Westbridge Road" sign - on 140 Westbridge Road

Commemorative plaque at 42 Vicarage Crescent - to Edward Adrian Wilson reads: LCC. Edward Adrian Wilson, Antarctic explorer and naturalist (1872-1912) lived here.

7-9 & 10-11 Battersea Square Battersea High Street (formerly Nos. 11- 15 & 17-19 odd) – Nos. 7-9 are a part-2-part-3 storey L-shaped corner building with later (1866) timber infill, which was formerly a post office. Nos. 7-8 form the historic core of the building and are constructed in stock brick with timber sash windows. The centre element is more richly decorated, the windows having surrounds and bracketed pediments. Plaques reading ‘London House’ flank central ‘Bennett Established 1780’ installed circa the same time as the ground floor infill. Slightly projecting central elements has decorate urns while lower sides have an ornate balustrade. No. 7 is taller at three stories and has Georgian-style flat window heads, simple lintels, and an Italianate bracketed cornice. No. 9 is a later construction (1980–1) designed to replicate No. 7 and replaced an earlier, shorter building. The shopfront is a mix of historic and contemporary elements, primarily glazed at to serve the restaurant use.

Nos. 10-11 forms a simple 2 storey corner building in white render. The corner shopfront is attractive with curved window and historic fascia, stallriser, and corbels, while the second shopfront to No. 11 is of less interest. The first floor has simple two-over-two timber sash windows with surrounds and prominent keystone details, with three to Battersea Square and two to Westbridge Road. Simple parapet roof.

St John's Estate, Battersea – Built in 1931–4 on the site of the former St John’s Training College, the estate represents Battersea Borough Council’s main inter-war housing effort. The estate was built under the Borough Surveyor, W. J. Dresden, principally to the layout devised by the LCC architect R. Minton Taylor, with five five-storey blocks positioned in a roughly symmetrical layout.

Winfield House and Eaton House are linear blocks to the east and north of the monumental central group, which consists of the quadrangular Archer House and White House, linked together by the much smaller Haythorn House. This forms two tight internal courts with an open court between (intended to be a playground, but used as parking), broadening out towards Vicarage Crescent.

Regular four-storey elevations of yellow and red brick with sash windows rise to the cornice; the fifth storey is mostly embedded in the mansard roof but brought forward to the front plane in the projecting central feature. The open balcony access to all the flats is concealed at the backs and within the two courts.

60 Battersea High Street – An attractive 2 storey pub, a beer house has stood on the site since at least the early 1840s, and the core of the building may be earlier though it has been much altered and extended and is a composite of these changes. The present pub is a simple brick, two bay construction with timber sash windows to first floor. Pub entrance has balanced set of alternating doors and windows with moulded stallrisers. Pilasters and corbels are retained and plain. The altered M-shaped roof is black slates with pair of red brick stacks at each side. Blank side elevation.

108 Battersea High Street - Plaque commemorating Katherine Low