Alton Estate

Conservation Area Appraisal No.46

Contents

- Introduction

- Appraisal Part 1

- Character Area 1: Alton East

- Character Area 2: Alton West

- Management Plan

- Appendices

Introduction

1.1. What is a Conservation Area?

The statutory definition of a conservation area is an ‘area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’. The power to designate conservation areas is given to local authorities through the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservations Areas) Act, 1990 (Sections 69 to 78).

Once designated, proposals within a conservation area become subject to local conservation policies set out in the Council’s Local Plan and national policies outlined in chapter 6 of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). Our overarching duty which is set out in the Act is to preserve and/or enhance the historic or architectural character or appearance of the conservation area.

1.2. What is the purpose of this document?

The Appraisal will help the Council to fulfil a statutory duty to draw up and publish proposals to preserve and enhance the character and appearance of the Alton Estate Conservation Area. This is achieved by defining the unique characteristics which make the Alton Estate so special and by identifying the threats and opportunities to its conservation and enhancement.

These are the foundations for developing practical policies and proposals for the management of the Conservation Area, which will enable it to sustain its special interest.

The appraisal will identify positive features of the special character which should be conserved as well as identifying negative features which would benefit from future enhancements.

It will take account of the:

- Historic interest

- Architectural interest and built form

- Locally important buildings

- Spatial analysis

- Streets and open spaces, parks and gardens, and trees

- Settings and views

- Other heritage assets

This document has been produced using guidance set out by Historic England, Understanding Place: Conservation Area Designation, Appraisal and Management’ (2019).

Location and Setting

The Alton Estate Conservation Area forms one of the most distinctive areas of Wandsworth - bounded to the north by Clarence Lane and the related grounds of Grove House, (listed Grade II*) the grounds of Grove House are included in Historic England’s Register of Historic Parks and Gardens; to the south and east it is bordered by Putney Heath - the Kingston Road (A3) creates a physical separation between these two areas; on the west it borders the impressive landscape of Richmond Park. The area slopes fairly consistently, sometimes gently, sometimes quite dramatically, from north-east to south-west, with land at its highest generally around the five listed slab blocks in Wanborough Drive.

The Alton Estate Conservation Area comprises two main parts - Alton East and Alton West (Alton East being the first phase of development 1951-55, then followed closely by Alton West, 1955-59). The Conservation Area lies alongside Roehampton Lane (A306) with direct links to Kingston Road; both are busy traffic routes. Danebury Avenue forms a key spinal route through the heart of the Conservation Area. The southeastern area sits in close proximity to three other significant Conservation Areas – Putney Heath, Dover House and Roehampton Village Conservation Areas, accessed via Roehampton Lane, with Roehampton Village offering further access to shopping facilities.

Designation and Adoption Dates

Alton Estate Conservation Area was designated on the 15th March 2001.

Following approval by the Executive at its meeting on the 21st November 2022, it was agreed to carry out a public consultation on this Appraisal between the 10th February and 24th March 2023.

This Appraisal was adopted on the 31st of August 2023.

Other Planning Designations

The Greater London Archaeology Advisory Service (GLAAS) completed its review of Wandsworth Borough's Archaeological Priority Areas (APAs) in 2017. Part of the Conservation Area lies within the Tier 2 APA of Roehampton. The full review can be found on the Historic England website as well as further information and guidance on Archaeological Priority Areas.

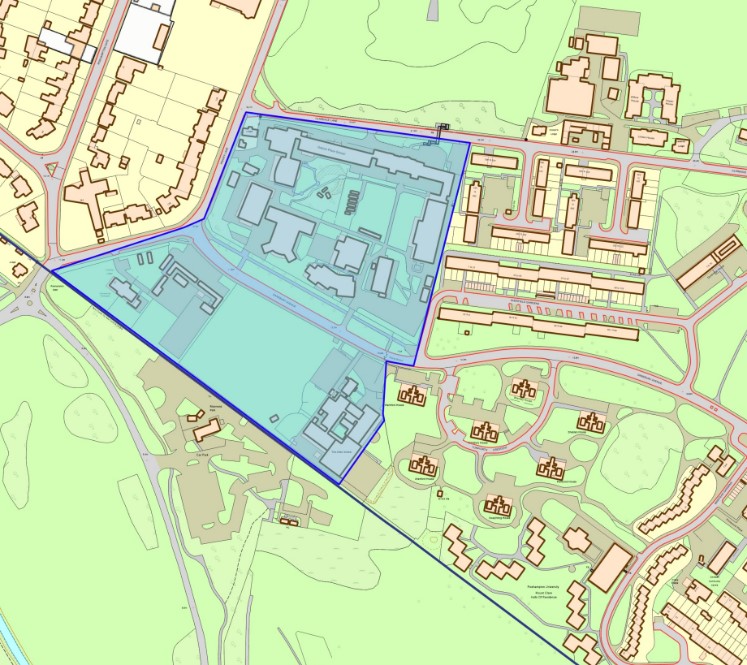

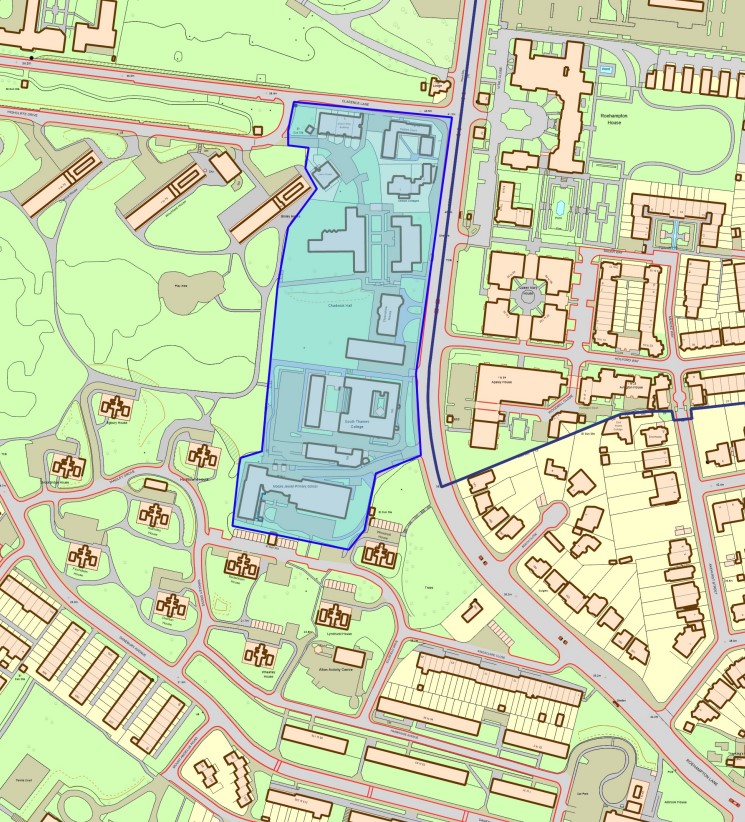

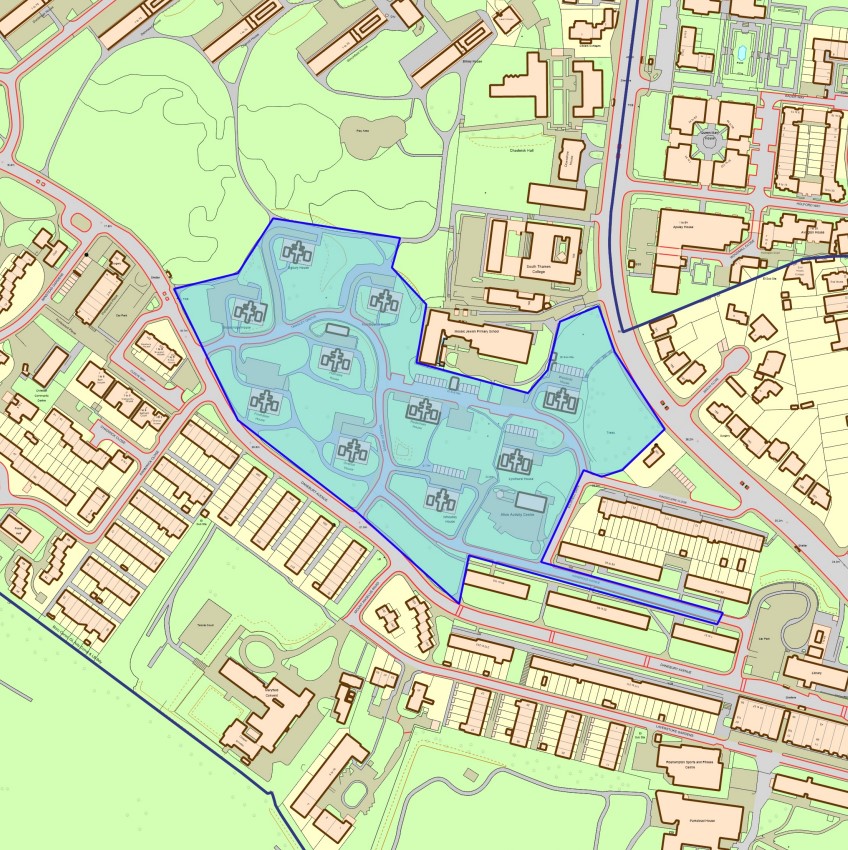

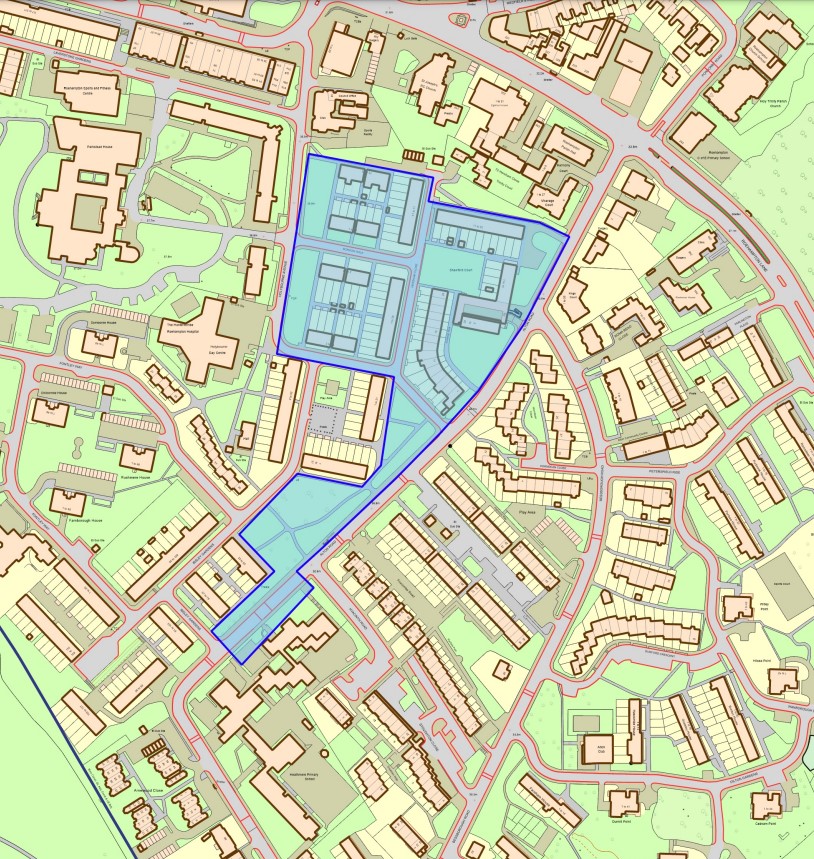

Map of Conservation Area

Appraisal Part 1

Summary of Special Character

The Alton Conservation Area was designated on the 15th March 2001. It covers 58.1 hectares and has more listed buildings, in particular Grade I and Grade II*, than any other conservation area in the borough. The importance of buildings is emphasised by their listed status, and some of those in the Alton Conservation Area are among the finest listed buildings in the borough - Mount Clare and Parkstead House (formerly Manresa House) are listed Grade I. Downshire House and the Temple to Mount Clare are Grade II* as are the five 'slab' residential blocks in Highcliffe Drive ((Binley, Winchfield, Charcot, Denmead and Dunbridge Houses) and the Bull statue at the foot of Downshire Field. There are many other Grade II listed buildings as well, including the distinctive bungalows of Minstead Gardens.

In June 2020 the landscape component of both the West and East Estates was Registered as a Historic Park & Garden by the Government at Grade II. This further extends the heritage protection across the Conservation Area and now means that the majority of the area is covered by national designation.

What gives the Conservation Area its special sense of place is the environment created by its atmospheric landscaping, historic layout and the architectural quality of buildings. The area's built form, while contemporary with the surrounding area, derives from the range of building scales and overall consistency and use of materials. The special character of this Conservation Area is derived from these unique characteristics expressed in its architectural and urban qualities.

Developments of distinct historical eras and styles of architecture (Georgian, Victorian and Post-War/Modernist) are expressed alongside the distinctive landscaping, creating areas of important open space. The Alton’s character is of substantial historical and architectural interest and derives from the layers of significance encapsulated by distinguished individual buildings from the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries, all set within an outstanding historic landscape, largely based on the Council’s Alton Housing Estate and the gardens of the surviving Georgian villas.

Examples of other impressive but unlisted individual buildings are: Ibstock Place School, Maryfield Convent, Cedars Cottages and Hartfield House. Generally, those areas that fall outside the Conservation Area simply do not have the same consideration, in terms of architectural or historic interest and care of detailing and landscaping that are strong and consistent with those that fall within the Conservation Area.

Some of the unlisted point block buildings are now considered for candidacy for the local list due their group interest as part of the original estate masterplan and their own interrelationship with the listed landscape.

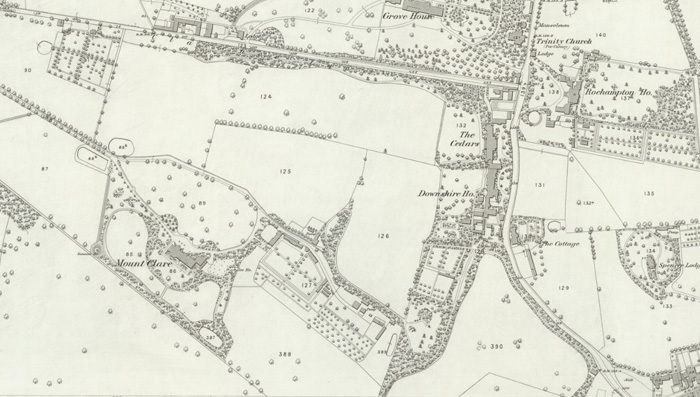

Fig. 1: Mount Clare and Downshire Houses (OS Map Surv. 1867, Pub. 1871)

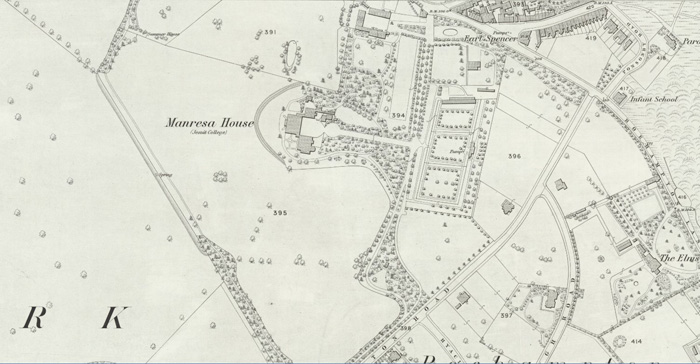

Fig. 2: Parkstead House (OS Map Surv. 1867, Pub. 1871)

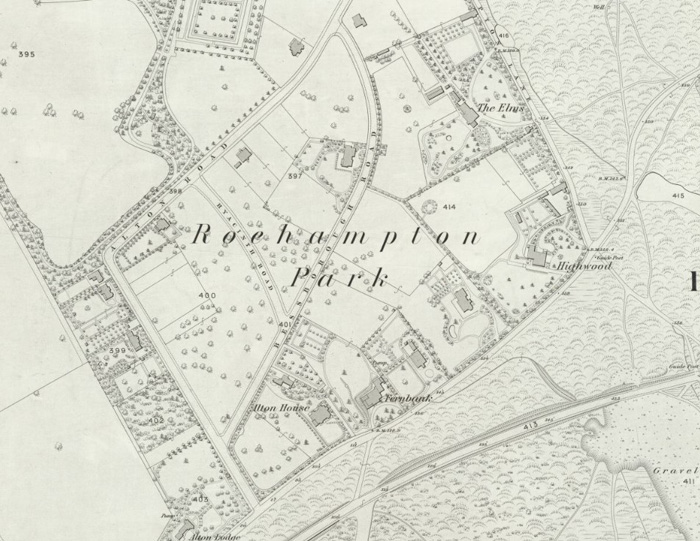

Fig 3: The Alton East area (OS Map Surv. 1865-7 Publ. 1869)

Historical Development

Georgian to Victorian Periods

In the eighteenth century Roehampton offered something uniquely desirable - a position away from the congested city centre, yet alongside the royal playground of Richmond Park. But access to the city was poor. When the first Putney Bridge opened in 1729, it improved the journey to London and aristocratic families were tempted to acquire land to establish country estates next to the Park. Travel conditions were still far from ideal, particularly in winter, so the houses they built were mostly intended for summer residence only.

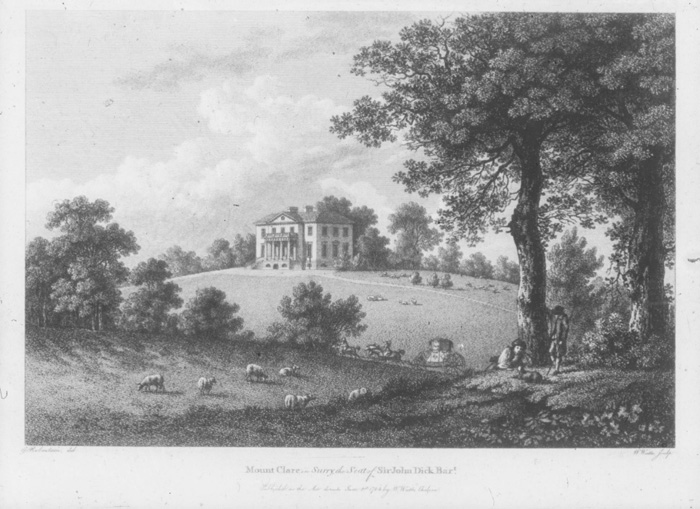

Fig. 4: Mount Clare, the House of Sir John Dick, built for George Clive in 1772

Hence the Georgian buildings that survive are smart but small classical villas. Two of these, “Manresa House” (later Parkstead), built for Lord Bessborough in 1760 (and subsequently much extended), and “Mount Clare”, for George Clive in 1772, were designed by the leading architects of their day and are now Grade I listed buildings. The less distinguished Downshire House gets its name from The Marquess of Downshire, the most prestigious early owner. All three houses were sited to take advantage of the gently rising slope to obtain commanding views across Richmond Park.

All three of the estates, which contained these houses were, in the fashion of the day, extensively modelled to improve on their natural qualities. Most notably, around 1774-5, Clive, the owner of Mount Clare, employed 'Capability' Brown to improve his park, and over the years all the estates benefited from extensive tree planting, both native and imported species, much of it designed to focus on pleasant views and screen out unwanted ones. Small parcels of land were exchanged between the various estates, whose owners appear to have been good neighbours. In 1913, the Doric temple now to be found in the grounds of Mount Clare (and itself listed, Grade II*) was moved there from the grounds of Parkstead.

Fig. 5: Rear elevation of Mount Clare

After the death of his wife, the 3rd Earl of Bessborough preferred to live in London, and Parkstead was leased out from 1827, under the name Roehampton Park House. The first major change to this Georgian aristocratic landscape came in 1858 when the 5th Earl of Bessborough, who had never lived at Roehampton, sold the house and all its grounds to the Conservative Land Society. The house was acquired by the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) who renamed it “Manresa”, in honour of their founder’s Spanish origins. They also took forty-two acres of the estate. The rest, keeping the name “Roehampton Park” was divided up into relatively small parcels to be developed for Victorian villa-dwellers. The Jesuits established a noviciate, gradually expanding over the years as they flourished. They were to occupy the house for 100 years, until the time of the next major change.

12 Roehampton Court was built in 1914 in the Georgian style and designed by architect Frank Chesterton. It was later converted to a convent and renamed Maryfield Convent in 1927 when it was bought by The Poor Servants of The Mother of God. The building was extended in this time with a new wing and Chapel. The building was damaged during World War II from incendiary bombs and then re-built in its original design. The building continues to be used as a convent although other uses were introduced such as a residential home. The building was renamed the Kairos Centre in 1995 as part of works to add a new wing. The building is locally listed.

Fig. 6: The town centre of Roehampton before the London County Council (LCC) development

Fig. 7: Parkstead House, circa 1760

Fig. 8: The original gates to Mount Clare, now lost

Fig. 9: Mount Clare from the rear

Fig. 10: Mount Clare from the front with its Victorian extension, now removed.

Fig. 11: Mount Clare, Minstead Gardens. View of lodge and entrance gates C1952

Fig. 12: View of Mount Clare from Downshire Field once much of the estate has been constructed. The street with the Bungalows is formed on the same route as the original carriage driveway.

Fig. 13: Downshire House, also from Roehampton Lane

Fig. 14: Rear elevation of Downshire House

Fig. 15: Downshire House from Roehampton Lane

Fig. 16: Parkstead, then Manresa, when used as a Jesuit College. This avenue is looking west to the rear of the main house.

Post-War Housing –The London County Council (LCC)

In the late 1940’s, the LCC bought Roehampton Park and the three Georgian country estates, all by then in institutional use. The LCC resolved to restore the eighteenth-century houses and to develop their grounds and those of the Victorian villas with new housing. The result was a comprehensive, careful development of housing and landscape that was to be the LCC's flagship for the 1950s. The Roehampton project coincided with the arrival of new blood at the LCC Architects Department, and so benefited from a fresh approach to housing design. The project was divided into two phases, with Manresa House in the middle. Following the compulsory purchase of two-thirds of their land, the existing Jesuit community had retained about 15 acres. Their seclusion increasingly compromised as work progressed, they decided in 1961 to move away, selling the house and remaining land to the LCC for educational use.

The first phase of new housing to be developed was Victorian Roehampton Park, which became the Portsmouth Road Estate, later Alton East. Next came the eighteenth-century landscape to the west of Parkstead, originally known as the Roehampton Lane Estate, but renamed Alton West after completion.

Alton East

The Alton East architects team epitomised a new approach, concerned with every detail of design, plan and landscape. Despite the need for economy, they tried to bring a touch of brightness and individuality. They were less preoccupied with monumentality and originality than the Alton West team. The fresh but friendly architectural forms they developed displayed a Scandinavian influence.

Abercrombie’s County of London Plan proposed densities for London, ranging from 200 persons per acre (ppa) in the centre to 70 ppa at its limits. At Roehampton a density of 100 ppa was proposed, as the open space of Richmond Park lay alongside. The Plan also promoted ‘mixed development' i.e. flats and houses, as a way of achieving these high densities without monotony. The retention of the existing landscape was a key concern.

The team decided that a fairly slim tower could sit neatly on the site of a Victorian villa and leave its planting undisturbed. They coined the name 'point block’ from the Swedish 'punkthus'. The blocks had a compact plan of four flats per floor, achieved by means of mechanically ventilated bathrooms, the first in any public housing in Britain. The point blocks were clustered near Roehampton Lane and the Portsmouth (now Kingston) Road to shield the site from traffic noise. Here they could stand in the biggest of the former villa gardens, and the land was highest, so the blocks exploited the natural topography. Ten point blocks were listed in 1998.

Fig. 17: Alton East, not long after construction

Fig. 18: Flerbostadshus Punkthus Exteriör 1950s, inspiration for the Alton East point blocks

Alton West

The Roehampton Lane site was far larger than Portsmouth Road, and its landscape more open and broader in scale. The bulk of it comprised the grounds of the late eighteenth-century estates. Many of the principal features of the eighteenth century landscape determined features of the new landscape. Danebury Avenue is essentially aligned along the line of the lane from Priory Lane, past the gatekeeper’s lodge to Mount Clare. The five dramatic slab blocks are set in Downshire Field, the principal part of the grounds of Downshire House. The team brought in to plan the new housing was also very different from that employed at Alton East. The Architect-in-Charge was Colin Lucas, an eminent modernist from the 1930s who as a member of the firm Connell, Ward and Lucas had designed many notable private houses, including the listed No 26 Bessborough Road (1939) in Alton East.

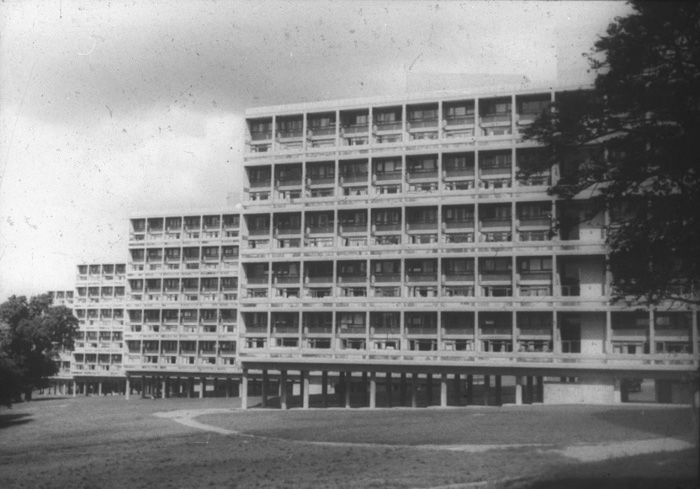

Design work began in 1951 with the presumption that a maximum amount of parkland should be left open for amenity and landscape values, and that as many tenants as possible should have views over Richmond Park. The group wanted high buildings, planners from elsewhere in the LCC preferred more low houses, and the end balance was a compromise. That summer the team had been to see the just completed Unite d'Habitation by internationally famous architect Le Corbusier at Marseilles, France. It was an influential experience. They realised that a slim slab, one flat deep, would allow every unit within it a view of Richmond Park. It could house more flats or maisonettes than a point block and could be cheaper, and that it could be a way of putting more maisonettes – then popular – on to the site whilst retaining the open quality of the sloping Downshire Field. In the original design the slabs were placed parallel and overlapping as now, but side-on near the top of the slope. The Minister of Housing, Harold Macmillan, objected to this 'continuous wall' overlooking a royal park. So between 1952 and 1953 the orientation of the blocks was changed to give the present massing into the slope of the hill, gaining dramatically in architectural power at the expense of residents' view.. Permission to start on site was received in 1954 and the main portion of the Estate was finished by late 1958. The five slab blocks were listed as buildings of special architectural or historical interest in 1998.

The shopping parade in Danebury Avenue, completed in 1959-60 and the library, in 1961, are outside the Conservation Area. The library has architectural interest, distinguished in part by its curved walls and undulating roof form but also by the associated (though detached) Allbrook House, which seems to float above - it too has an interesting form and details, including decorative block detailing to its balconies, which unifies and softens the harshness of the structure. The library was one of the last buildings in the original development of Alton West. It was designed by John Partridge of the LCC Architect’s Department incorporating ideas from Wandsworth Council's library service. It was opened in September 1961 by the children’s author Noel Streatfield. There was originally a mural by Bill Mitchell in resin and plastics.

Central heating was by a district heating system serving all the high buildings and the two infant schools built as part of the scheme. The system has a dramatic tall chimney at the end of one of the slab blocks (Winchfield House). It was too expensive to bring the district heating system to the pensioners’ bungalows, so each was given a fireplace, served by a slender, circular concrete chimney poking through the flat roof– a quirky anachronism in a modern Estate. The communal system is now abandoned and has been replaced by individual systems across the estate.

Fig. 19: A high shot of the two groups of point blocks showing the growth of trees

Fig. 20: Point Blocks to the west of Mount Clare

Fig. 21: Alton West slab blocks (photos from the Wandsworth Heritage Archive)

Fig. 22: Point Blocks and distinctive original boundary fencing which was widespread throughout the estate

General Description

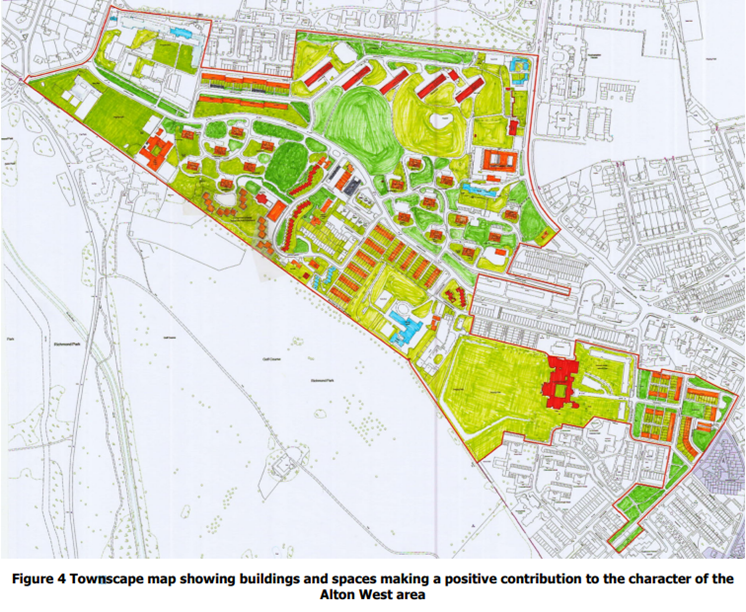

The character of the Conservation Area is made up of the sum total of its buildings, streets, green space and views, and can be harmed or improved by intrusions or alterations to any of these elements. The Conservation Area can be divided into two areas of separate distinctive character (Alton East and Alton West), which is largely determined by the landscaping and analysed in the following pages of this document.

Due to the vast size of the Alton Estate and in an attempt to 'humanise' the area, the Council's Housing team has broken down the Estate into ten manageable neighbourhoods: Highcliffe, Tunworth, Danebury, Ibsley, Tangley Manresa, Amewood, Hyacinth, Wanborough and Norley neighbourhoods. This has helped to make the Estate less impersonal for the residents and also more understandable for people with different levels of familiarity to find their way around.

Its special interest derives in part from the architectural contrast of buildings and their setting – both historic and modernist set at various heights within impressive (often undulating) landscaping. The relationship between landscaping and main routes is also an important feature. The main spinal route within the Conservation Area (in Alton West) is the long gently winding boulevard-like Danebury Avenue, which gathers in other routes at its various frequent junctions, leading to shorter, more curving access roads. This element of form provides a constantly changing focus and establishes how buildings are set within their local landscapes. There is also a spur along Harbridge Avenue, comprising the existing tree-lined avenue which is included within the Conservation Area due to its illustration of the former carriageways which served the large houses.

From various locations it is possible to follow each route or avenue visually up to a point - each of these avenues tends to have its own distinctive style, formality and landscaping; generally, lower scale housing tends to create formal avenues; the slab and point blocks create informal clusters (the point blocks more so, being set in almost radial groups); in many instances due to the nature of their architecture, function, generous amounts of landscaping and historic development, the education and community buildings tend to have more of a private estate feel to them. The landscaping, road layout and relationship of built form to open space together comprise the distinguishing feature of the entire Conservation Area.

Although in close proximity to Roehampton Village Conservation Area, much of the Alton Estate has a park-like atmosphere and remains undisturbed by the busy street activities associated with this area. Each character area is accompanied by a townscape map which shows at a glance the buildings and green space that make a positive contribution to the character of the Conservation Area.

Building Use

The Alton Estate Conservation Area has a quiet residential character and very few of its buildings are dedicated to anything other than housing. The idea of residents mixing normal life with social needs in close proximity was considered, however, developing housing to meet demographic changes was not fully addressed. Future changes in social needs was catered for to a limited extent and this aspect of the Estate is a little restrained in terms of the mixture of uses, which can be seen in the land use make-up of the area.

The housing make up includes: 27 point blocks arranged in three groups (two in Alton West and a further two in Alton East); five 11-storey slabs of maisonettes; several terraces of 4-storey maisonettes, 2-storey terraced houses and groups of pensioners’ people's bungalows. Further residential building types can be seen with student accommodation where educational uses exist.

There are now two schools - Alton Primary and Ibstock Place schools (Danebury Primary was demolished to make way for housing). There are the eighteenth and nineteenth century buildings in educational use e.g. Roehampton University and South Thames College. Other uses include community centres found in both Alton West and Alton East.

More community facilities, shops, a library and church can be found outside the Conservation Area.

Building uses also contribute considerably to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area. These not only have a direct influence on the building types and make-up of an area but also on the appearance, impression and use of the spaces and streets. The uses create activity at different times in the day and also provide variety in building type within an otherwise sometimes repetitive townscape. Original building use that once characterised the individual streets in the Conservation Area have not changed significantly. The educational facilities are important uses within the Conservation Area and have for several decades secured the continued use of some of the area’s most important buildings such as Mount Clare and Parkstead House.

Landscape

The Alton Conservation Area is a rare, possibly unique combination of eighteenth century and twentieth century picturesque landscape. There are scores of magnificent mature trees, including one, a Lucombe Oak, which is on the list of Great Trees of London. There are Tree Preservation Orders on the trees around Mount Clare, Parkstead and Downshire House and at 66 Alton Road. The landscape of Alton East and Alton West were designated as Historic Parks and Gardens in June 2020. The landscapes of Mount Clare created by Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown and Parkstead are included in the Council's list of Parks and Gardens of Local Interest.

Perhaps uniquely, Alton West also features two public sculptures, both now listed. At the corner of Danebury Avenue and Tangley Grove is a fine bronze sculpture of a bull, designed by Robert Clatworthy and listed at Grade II*. First exhibited in plaster form at the LCC's sculpture exhibition in Holland Park in 1957, where it caught the attention of A. W. Cleeve Barr, one of the senior architects working on the site, who secured approval for a special casting in May 1959. Clatworthy chose the site. The LCC commissioned a casting to be made in 1961. Ten feet in length, it is a shaggy expressionist figure of a bull that seems about to turn its head, in a heroic yet friendly image. A smaller version is at the Gibberd Garden in Harlow, Essex.

The area surrounding the Bull sculpture has seen some change in the form of car parking, provided to address the needs of residents of Brockbridge House. It is unfortunate that the parking area is so close to the sculpture, encroaching on its original green setting.

Two years later, another sculpture, “The Watchers”, three abstract figures in bronze by Lynn Chadwick, was sited in the garden of Downshire House (Grade II), with one of the three sculptures unfortunately stolen, the remaining two removed by the university for protection and repair - these are now repaired and restored along with the third Watcher and reinstated to the original location.

In Alton East there are several large surviving rocks (boulders) scattered about the grounds of the five point blocks located on Wanborough Drive (Blendworth, Hilsea, Eashing, Hindhead and Whitley Points); they are of the Scandinavian influence the architects introduced to the area along with Pine, Deodar Cedar and Norway Maple trees.

Routes and spaces

The Alton Estate Conservation Area has a unique and distinct layout, based on the principles of "Picturesque" landscape. Movement through the Estate is varied and heavily dictated by the landscape, much of which is determined by the historic topography of the land that helped shape the area. Because of this, there is no simple, dominant street pattern such as that found in traditional Victorian terraced housing.

Primary routes are the central spine of Danebury Avenue (Alton West) and Bessborough Road (Alton East) and those that form the Conservation Area’s boundary – to the north and south-eastern edges. Danebury Avenue creates an island effect in the centre and is limited to pedestrians and some traffic - the area is poorly served by transport compared with other parts of Wandsworth, impacting on the area’s ability to attract custom.

The other “streets” or avenues are secondary, lined with trees and often with parked cars, an aspect that struggles to be positively integrated within the Estate. Intimate routes can be found in Alton East created by the swathes of mature trees and layouts of the point blocks to the south-east.

At times it is difficult to establish what areas are private or public, paths often lead to nowhere or loop with no clear way of moving through the Estate. There are generous areas of green space forming an attractive visual setting for the larger buildings, but with no other obvious function. Some areas of the Estate are in need of rationalising; a new look at ordering networks of green spaces and paths would help make spaces relevant to people. Spaces and routes would benefit from being more multi-functional and connected, allowing residents and those with different levels of familiarity to be able to function flexibly, i.e. move through or visit and in doing so, gain an immediate understanding of the Estate and a sense of place.

There are always opportunities to glimpse other green spaces or gardens as the Estate is not tightly built up. Both private and public landscaping (including back gardens) are fundamental in defining the visual character of the estate and how routes and spaces are experienced. The close proximity to Richmond Park (mostly from Alton West) extends the green space of the area and reinforces its significance.

The oldest buildings are set back in generous plots, often behind high boundary walls or tucked behind layers of other housing or mature landscaping. Large-scale developments (e.g. student accommodation) and later infill have attempted to address the street more directly but in some cases they fail to respond to a specific historic pattern of development found in the area or relate to that strong articulation of form that is synonymous with modernist architecture.

Views

The topography of the Alton Estate Conservation Area is unique and views from it to Richmond Park are spectacular and fundamental to its special interest.

Wider views

Views played an important part for the architects designing the Estate. Of particular relevance are those to Richmond Park - high buildings were planned to have impressive views over the Park, spanning around 10 miles - this view is the most significant of the Conservation Area. There are long range views towards Richmond Park from those more elevated areas within the Conservation Area. Shorter, curving roads often obscure views into the Conservation Area and some views out of the Conservation Area are limited for this same reason. Two of the most breathtaking views of the Alton Estate are that of Alton East towards London on the Kingston Road and of Alton West from Richmond Park.

Mount Clare, Downshire, Parkstead

Some of the most important views within the Conservation Area are the views from and of these three listed Georgian mansions. With Mount Clare the important outlook is to the rear through to Richmond Park and to the front over the paddock and towards Downshire Field and the slabs. Views towards Mount Clare primarily are from across Downshire Field and whilst these are currently compromised, they can still be appreciated at certain times of the year. Downshire House has only short street views to the front but from the back views out from the garden and across Downshire Field are important. Views towards the rear of Downshire are also important and help to emphasise the area’s former history. Parkstead has important views out towards Richmond Park and over some low-lying buildings just below the ha-ha in Laverstoke Gardens. These views are perhaps the most significant as they represent the last of these three houses to enjoy something of its previous outlook across the park, one of the principal reasons the houses were located in this area.

Local townscape views

The streets of the Conservation Area vary; they are often short and curved, many of which radiate off the long curving Danebury Avenue - this combination provides a range of views to related streets/avenues and is a strong character of the area. There are long and short vistas to the ends of streets - in most cases these are long but often interrupted by curving streets.

There are direct views to the slab blocks from Minstead Gardens, capturing a range of buildings and their landscapes, including the bungalows and Mount Clare and Picasso House, (former refectory building). The views between buildings are an important feature of the Conservation Area - these range from a mixture of mature landscapes to communal or private gardens, especially where one boundary or neighbourhood meet another. Where communal gardens or back garden boundaries meet, for example at the end of a residential block, terrace or road - there are short, long and glimpsed views across green gardens and communal landscaping.

Glimpsed views

Glimpsed views occur a great deal throughout the Conservation Area, especially from Roehampton Lane and Kingston Road and also from within the Conservation Area itself. There are also good quality short range views and glimpses through to gardens and grounds of educational buildings, seen from various gaps between building plots and also visible from streets both inside and outside the Conservation Area - for example from Fontley Way (outside the Conservation Area) and Holybourne Avenue (within the Conservation Area) to Parkstead House and its related grounds.

Some buildings outside the Conservation Area have an influence on the area's character, particularly noticeable along Harbridge Avenue where the avenue of street trees forms part of the setting of the Conservation Area, just off Danebury Avenue, where there are shops, the library and Allbrook House (the latter falling outside the Conservation Area).This would also be the case if taller buildings were proposed to some of the corner or junction edge locations along Roehampton Lane and Danebury Avenue. Careful scrutiny will be given to any such proposals; including how well the development responds to and reinforces locally distinctive patterns of development, landscape and culture typical of its neighbourhood and also the impact the building has at street level and its immediate surroundings.

Buildings Audit

The map in the introduction shows the varying contribution which buildings within the Conservation Area make towards the overall architectural and historic character of the area. The special interest of Alton Estate Conservation Area primarily derives from the original buildings, which have survived since the Estate’s construction. These buildings within a Conservation Area can be of varying architectural and historic character and whilst some are positive contributors to the overall special interest of the area, others can be neutral or negative contributors. It is also important to note that the age of a building does not necessarily dictate its value, and new and old buildings can all be positive, neutral, or negative.

In the case of Alton Estate Conservation Area, the majority of the buildings are positive contributors to the special interest of the Conservation Area. These include the heritage assets identified, and the private and Council built residential housing, which makes up the vast majority of the Conservation Area.

Positive Buildings

These buildings make a positive contribution to the special character of a conservation area. They are a key reason for designation and often make up the majority of buildings within a conservation area. Changes to these buildings should take into account their significance and seek to preserve or improve this.

In the case of Alton Estate Conservation Area, the majority of the buildings are positive contributors to the special interest. This includes the heritage assets identified, and the private and Council built residential housing, which makes up the vast majority of the Conservation Area.

Neutral Buildings

These buildings are often of average design quality, which make no special contribution to the townscape or the heritage significance of an area. Improvement to these buildings will be encouraged within the planning process where opportunities arise.

Negative Buildings

These buildings should make up a very small minority of a conservation area and are buildings which are of poor design quality or have a poor relationship to the surrounding townscape or architectural character.

Heritage Assets

Listed Buildings

These are designated heritage assets by the Government on advice from Historic England. They have architectural and historic significance of national importance. Local authorities have a statutory duty to seek to preserve and enhance. Alton Estate comprises the majority of the borough’s most highly graded heritage assets with several at Grade I and Grade II*.

Locally listed buildings

Also known as non-designated heritage assets, these are not considered to be significant enough for the national list but still merit the term ‘heritage asset’ due to their local importance.

The Council holds a list of buildings that are of special architectural or historical interest at a local level. The list is a record of some of the historic buildings that are of particular interest, not just to this Conservation Area, but to the borough. These are different from buildings that are statutory listed for which consent is required for alteration. There are no additional planning controls over locally listed buildings other than those that already apply to the building; however, this designation is a material consideration under paragraph 203 of the NPPF (July 2021), which concerns non-designated heritage assets.

The Local Listing criteria can be found in Section 9 of the Historic Environment SPD (adopted 2016).

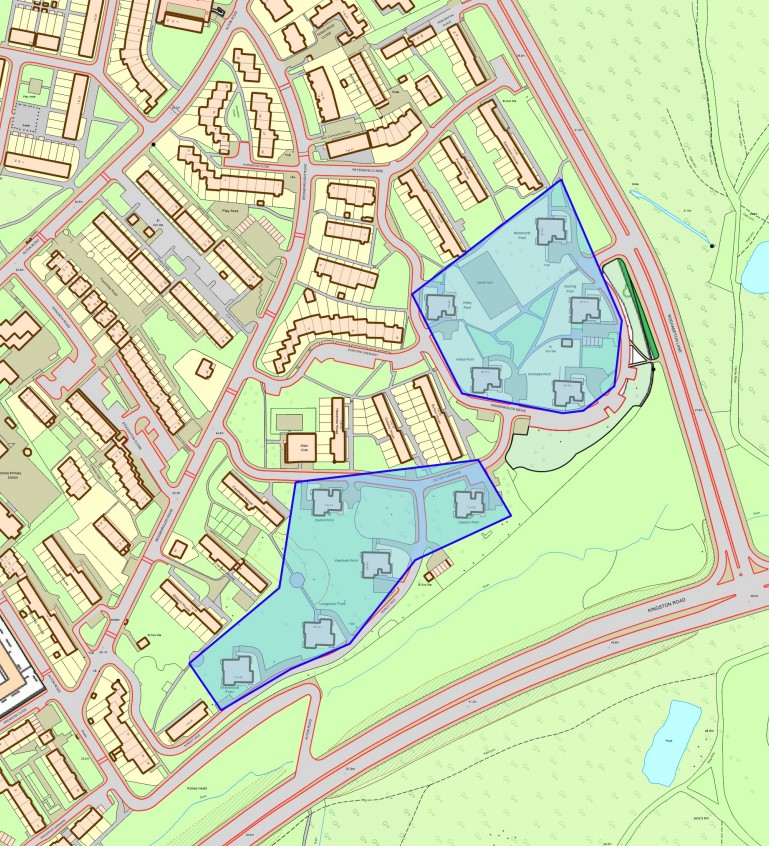

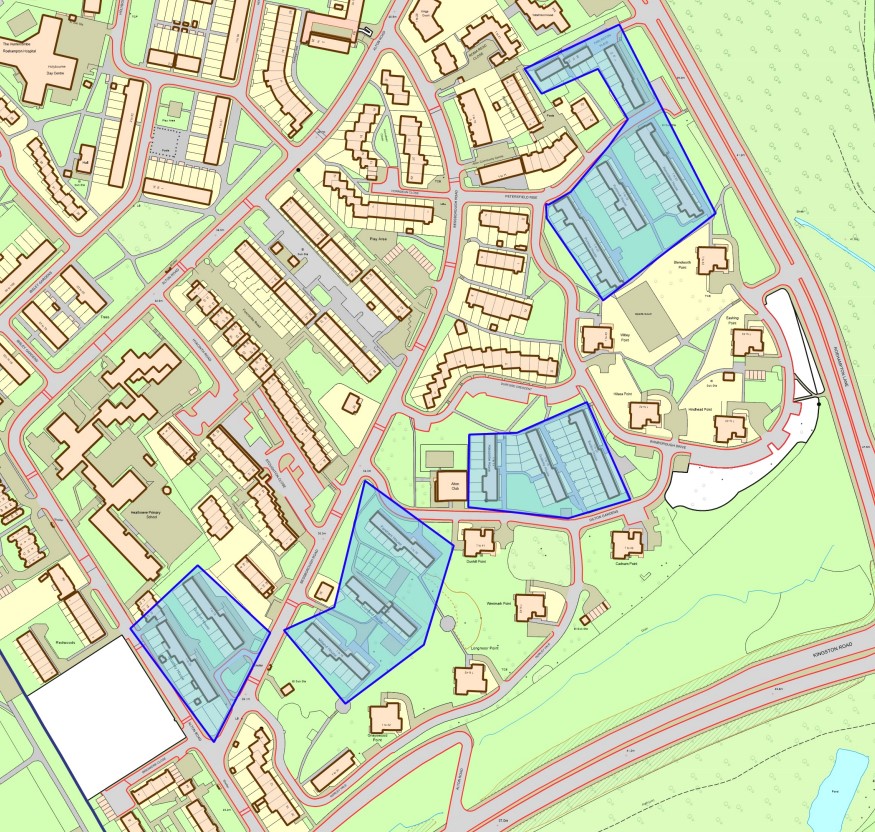

Character Area 1: Alton East

Alton East was built in 1952-55, at the time it was (and still is) seen as an ambitious architectural and social achievement and one of the showcase estates by the LCC. It is defined by the quality of its built environment, reflected by its lush Victorian landscaping, layered with the twentieth century landscape interspersed with a number of listed buildings and high quality 1950s public housing inspired by the Swedish idiom. Groups of housing similar in style and architectural treatment successfully combine to create a picturesque but informal townscape and every flat in all directions has a long green view. Harmony and building relationships are achieved through a consistency in scale and specific choice of materials. The character area is made up of: Wanborough Drive, Horndean Close, Durford Crescent, Dilton Gardens, and Norley Vale.

The area comprising the Alton East Estate is now predominantly a Registered Park and Garden, listed at Grade II.

Overall Townscape

The character area is rich in local townscape details that cumulatively give interest and quality to the street scene. The urban grain is created by a mixture of housing types, but it is the 10-11 storey, carefully placed point blocks, five along Wanborough Drive (Blendworth, Witley, Eashing, Hindhead and Hilsea), five along Norley Vale (Greyswood, Longmoor, Westmark, Dunhill and Cadnam) that provide the principal focus of its unique special character.

These blocks are of a distinctive design era, clearly associated with that of the modern movement. Key concepts of both form and function are evident in the scale, construction methods, materials, architecture and choice of finishes. This aspect of the Alton has a direct relationship with Roehampton Lane - this relationship is significant as this break in townscape offers an entirely different atmosphere to this part of the character area.

This character area is informally bounded by Roehampton Lane, Bessborough Road, Alton Road and Norley Vale, all of which vary in character in terms of building type and quality of architectural detailing, only some of the housing along these roads are within the Conservation Area and make up this character area. Those that fall outside the Conservation Area tend to be piecemeal and do not reflect the same design ambition as the other parts that are included.

The area's townscape has generally retained its scale and character. To a larger extent, changes tend to be at a domestic level, some building fabric has been disturbed by insensitive alterations – changes of this kind have a cumulative impact on the character of the area but still contribute to the area's identity and legibility. There is demonstrable evidence of properties being maintained and preserved - this common attitude upholds the integrity of the Conservation Area. However, the erosion of original details clearly manifests itself in other instances, such as the public realm.

Roads are not particularly wide; therefore any on-street parking tends to create a presence; however, the mature landscaping softens this impact in many cases. Buildings tend to be expressed vertically with mostly flat roof finishes and often set within generous gardens. The care given to small details is something most usually noted at Alton East, especially where the small scale of gardens has been retained.

To this day, the arrangement of the housing remains largely unaltered and its picturesque landscape striking.

Red = Nationally Listed

Orange = Positive contributor to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area.

Boundary Treatments

Front gardens and their boundary treatments are a part of an owner's private property that is also part of the shared public realm or townscape that is made up of street surfaces, street trees, pavements, street lighting and building frontages. Substantial photographic evidence is kept in the London Picture Archive.

There is little evidence of original boundaries, although there are some remnants of the historic boundary walls and paving (e.g. at the corner of Horndean Close and Bessborough Road) that once characterised the streets, but many have been lost to road or 'home improvements’. Heights and treatments differ, e.g. the stepped spanning wall to Alton Road and Bessborough Road is original and of gault brick, so too is part of the wall to Roehampton Lane that encircles Eashing Point and Hindhead Point.

Original boundary treatments are of low timber (slatted) fences above dwarf concrete walls or in cases gardens would simply come to the end of paths with no specifically marked treatment - some are complemented by trees and planting. Most fencing surrounding the point block entrances have now been replaced by loop topped, black metal rails. Original boundaries to the stepped terrace housing remain in Durford Crescent where the front gardens were bordered with simple tube metal railing with few supports. This is also present on some houses in other terraces and maisonettes. Also present on this street are substantial remains of original set pebbles creating a decorative divide between pavement and road.

The roads which cut through the landscaping are generally bordered by brick retaining walls, which remain high quality and add material interest to the landscape.

Boundary treatments are not always consistent in material but add interest and a sense of scale to the streetscene, often marking the boundaries between public and private spaces and in an attempt to personalise space. The existence of original boundary walls is a vital reminder of the area’s evolution and should be protected as far as possible.

Fig. 23: Alton East maisonettes with distinctive curving retaining walls which are characteristic of the way the landscaping and the highways meet

Fig. 24: Victorian wall fragment

Fig. 25: Modern replacement railings around the point block entrances

Fig. 26: Original and repaired brick walling to the terrace housing

Fig. 27: Original tube railings along the roads and hoop top railings around the point blocks

Fig. 28: Brick wall to the Roehampton Lane boundary of the estate

Fig. 29: Original metal tube railings around front gardens of maisonettes

Streetscape

Most original street surfaces have unfortunately been removed or overlaid with modern surfaces – there are some visible evidences of historic surfaces remaining e.g. at the corner of Horndean Close and Bessborough Road where the gardens are cobbled. Additionally, the granite setts and cobbles along Harbridge Avenue are of significance. All of these historic finishes should be retained as the remaining elements of them are a strong positive contributor to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area.

Although there remains some evidence of historic pavement surfaces, unsympathetic alterations to boundaries and the progressive loss of traditional paving materials and architectural details to modern materials has led to some erosion of historic character. This is considered to be a negative feature of the area.

Fig. 30: Petersfield Rise, original boundaries and front garden cobbles, which should be kept as they are positive contributors to the Conservation Area's character and appearance.

Landscaping and Trees

The green open spaces flow between the buildings and the street, and the pedestrian and highways both similarly wind through the landscape. Additionally, there are many instances of carless “streets”, at right angles to the roadways which prioritise people and the ability to enjoy the surrounding green spaces.

The landscape here is relatively tighter and more intimate than in Alton West, yet nevertheless enhanced by many fine mature specimen trees, including Cedars, Scots Pine (Pine trees represent a reflection of the acid soils that were formerly part of the heathland in the seventeenth century), Yew and Holly, all carefully retained from the Victorian villa gardens. Bessborough Road is partly bounded on both sides by long stretches of former hedgerows, comprising Holly and Yew, and tall Lime shelter planting. Alton Road features boundary planting of Lime and Beech, the typical traditional English landscape specimen tree, together with Yew hedging. Holybourne Avenue retains an intact stretch of Lime avenue, marking the entrance to Parkstead (Manresa) House. There are also fine Oak, Beech and Lime trees on the generous greens that form the focus of many of the groups of houses. e.g. Horndean Close and Durford Crescent. The larger blocks are generally well set back from the road and set within expanses of well-treed greenery.

Fig. 31: The typical winding road which cuts through the remains of Victorian villa gardens with their mature trees

Fig. 32: A selection of the varied and dense planting

Fig. 33: Trees of Alton East

Fig. 34: The boulders were a distinctive, planned feature of the Alton East landscape from the start and were inspired by the Swedish landscaping of their own housing estates

Fig. 35: Another image which shows the quality of the verdant planted environment and how the buildings and red brick sit well within this

Fig. 36: Some hardstanding is occasionally cut into the landscape and appears to be seldom used, although sometimes for parking

Fig. 37: The green landscape comes right up to the balconies on the point blocks, allowing the buildings to sit amongst the landscape and not just hardstanding

Architectural Quality

Alton East is characterised by its unique architectural quality, the high density of housing within the character area further improves this. The character area comprises about 744 dwellings. Paths and streets (avenues) are both wide and narrow and tend to be either tightly packed or grouped along: Wanborough Drive, Horndean Close, Durford Crescent, Dilton Gardens, and Norley Vale.

The housing was designed to three basic types with varying accommodation. There are randomly arranged short groups of two storey staggered terraces on pedestrian paths; four storey maisonettes and the eleven storey point blocks - namely Blendworth, Cadnam, Dunhill, Eashing , Grayswood, Hilsea, Hindhead, Longmoor, Westmark and Whitley Points (listed Grade II). So too is the private house at 26 Bessborough Road, designed by Connell, Ward and Lucas in 1938, described in the listing as “International Modern Idiom”.

Despite the range of styles attempted in architectural character, built form tends to have a relatively consistent scale, point-blocks are the exception with a strong vertical emphasis. The charm of the Estate lies in the fact that most buildings still have original details. Most are reflective groups; all share common facing materials and are linked by paths that form part of the landscaping.

The three key types are described below:

Sub-types

Alton East Point Blocks

The success of the Alton East point blocks lies in their relationship to the surrounding landscape. Designed in 1951 and built in 1952-5 under architect-in-charge Rosemary Stjernstedt (who had married a Swede) assisted by A.W. Cleeve Barr, Oliver Cox and the engineers Ove Arup and Partners. These blocks took their inspiration from Sweden where model welfare state housing had been built since the 1930s and used vernacular, rather than purely modern, materials. The unlisted point blocks at Alton West owe much to these earlier towers but differ in that they do not have projecting balconies and do not reference vernacular materials. What was novel about these flats was that they had internal bathrooms, so that four flats could be fitted on to one floor, making them economical to build. The style includes the grey ‘clinker block’ brickwork, which contrasts with the red brick of the lower blocks and especially the concrete panels of Alton West. The string courses which break up the brick façade and denote the floor levels are partially exposed elements of the reinforced concrete frame. The projecting service tower to the top is rendered white and rounded to ease its visual appearance.

The ground floor was painted and some still retains the original aluminium fenestration, as do the impressive staircases which act as an almost entirely glazed section which runs the entire height of the building. The floor plates are cleverly disguised by opaque glass. Each block is denoted by different patterned tile work at entrances (in fact one or two are repeats), designed by Oliver Cox, using white and two varieties of black speckled tiles to give the illusion of contrasting grey and near black. Each block also retains its original tiled sign. This was a cheap way of giving each block a degree of individuality, a technique still widely used today.

Each square block contains 42 flats with four flats to each floor arranged around a central lift core, with the exception of the ground floor which has three flats - the ground floor was set back partially and contained storerooms.

The towers were built on the higher part of the site, to make them seem taller, and some stand on the site of old Victorian villas to disturb the landscape as little as possible.

Fig. 38: Location of Alton East Point Blocks

Fig. 39: The distinctive, entirely glazed stairwells with the floor plates well hidden by thin stretches of opaque glazing

Fig. 40: Alton East point block with its projecting balconies and white brick, surrounded by trees

Fig. 41: An example of the original tiled panels and name signs, these at Longmoor Point

Fig. 42: Alton East point block, showing the glazing pattern

Fig. 43: The ground floors, now painted white, with their ground floor balconies

Fig. 44: A detail of the balconies, white brick, and floor plate band

Two-storey staggered terraces

The terraces are of a traditional brick construction with pitched roofs - most of the colour has been used externally and this is particularly so for the pleasing group forming the junction of Norley Vale and Alton Road.

Also much admired are some of the houses, particularly Horndean Close, a cul-de-sac whose staggered plan and combination of brick and painted finishes is particularly charming. The soft greys, greens and creams of some of the houses is original.

Originally all the doors were recessed within the porch section; they have now almost all been set flush with the wall.

Fig. 45: Image showing how the terrace houses are staggered

Fig. 46: Terraces on Horndean Close

Fig. 47: Terraces on Horndean Close

Fig. 48: Map of two-storey terrace housing in Alton East

Four-storey maisonettes

There are 11 sets of maisonette blocks, each comprising two ranges slightly offset from each other. The maisonettes have brick facings for external walls, with load bearing brick cross walls, reinforced concrete floors and pitched roofs. End walls were often carefully patterned with fine pointing - a pre-war craft tradition. One side is the deck access with rendered corridors and to the other side are projecting balconies. The original joinery is almost all replaced with modern equivalents but there is still strong visual consistency. Ground floor maisonettes have generous back gardens bordered by close boarded timber fencing.

The maisonette blocks, like the point blocks, sit within the generously wooded former Victorian gardens. They are set naturally within the landscape and the interesting topography and mature trees greatly enhances their setting and adds to their interest. They have a pleasing relationship with the point blocks where the contrast of low and high adds visual interest. Often the point blocks can be glimpsed over or passed the maisonettes, drawing the eye through the landscape.

Fig. 49: Elevation of maisonettes with projecting balconies to the upper floor units and rear gardens with fenced boundaries

Fig. 50: The front access side, with access to the lower units on the ground floor and upper units with gallery access

Fig. 51: Material contrast between maisonettes and the point blocks and showing how they sit within the landscape

Fig. 52: Map of the maisonette units of Alton East

Fig. 53: Townscape interest derives from the visual contrast between the low maisonettes and the tall point blocks, resulting in picturesque views

Other buildings

Also of significance is 26 Bessborough Road, designed by Connell, Ward and Lucas in the International style - a former doctor's surgery, later converted to a house. Listed in 1986 at Grade II, with a concrete frame with grey brick and stucco, the building is a well-preserved example of an early, inter-war period modern idiom house.

66 Alton Road (locally listed) is the last remaining of the Victorian villas within the area. Although outside the listed landscape and with a lesser relationship to the Alton Estate it is nonetheless an important reminder of the area’s previous Victorian character.

Alton House, another Victorian villa, has long since been demolished but at 33 Bessborough Road (locally listed), the lodge survives in good condition. This house sits within the listed RPG landscape and is a strong reminder of the former Victorian character and contrastingly interesting with the modernist housing. This is an important survivor, and every effort should be made to ensure the conservation of its architectural and

Fig. 54: 66 Alton Road (locally listed), a last remaining Victorian villa

Fig. 55: 26 Bessborough Road, Grade II listed

Fig. 56: 33 Bessborough Road, the lodge of the former Alton House and is locally listed

Character Area 2: Alton West

Alton West was built in 1955-59 and has a different character to Alton East but nonetheless successful in its own way. It too was ambitious in terms of its architectural treatment and response to the landscaping and existing Georgian villas.

The character area is defined by the quality of its built environment, reflected by its beautiful landscaping and the number of listed buildings in the character area. The eighteenth century villas and groups of housing similar in style and architectural treatment successfully combine to create a picturesque but informal townscape. Building relationships and connection is achieved through a consistency in scale and specific choice of materials. The character area is made up of several streets/avenues including: Danebury Avenue, Highcliffe Drive, Ellisfield Drive, Tangley Grove, Swanwick Close, Minstead Gardens, Harbridge Avenue, Holybourne Avenue and part of Laverstoke Gardens.

The trees and winding paths between slab blocks help to break down the otherwise monumental feel, as does the spacious sloping lawn of Downshire Fields, made up of curves and beautiful landscaping, which contrasts with the slabs. Alton West also features the two public sculptures – Clatworthy's bronze sculpture of a bull and Chadwick's “The Watchers”.

Public Realm

Boundary Treatments

Front gardens and their boundary treatments are a part of an owner's private property and also part of the shared public realm or townscape that is made up of street surfaces, street trees, pavements, street lighting and building frontages. Just as the houses are laid out in informal terraces or groups, so the front boundaries were designed to match this informality; this is especially the case for the point blocks, as spaces here are shared.

Although many mature trees, garden walls and other features were retained, and the point blocks carefully positioned to ensure they could benefit from the existing landscape, many original boundaries have been lost. Boundary treatments are not always consistent in material but add interest and a sense of scale to the street scene, often marking the boundaries between public and private spaces, and in an attempt to personalise space.

There are, however, parts of remaining boundary walls and paving of pebbles and granite setts e.g. Hersham Close, which contribute significantly to the character of the Conservation Area. Original boundary treatments are of low timber (slatted) fences above dwarf concrete walls or in some cases gardens would simply come to the end of paths with no specific marked treatment, some are complemented by trees and planting.

Streetscape

The care given to small details is something most usually noted at Alton East, where the small scale of the former gardens is retained. Yet at Alton West, too, attention is paid to paving surfaces, with use of cobbles (e.g. in Harbridge Avenue) as well as paviours and concrete; the low concrete walls are carefully poured and often curved. Nothing is too small not to merit thoughtful design. And though the use of a high proportion of concrete rather than brick gives an initial impression of toughness, the cleaning and restoration of the blocks over recent years has revealed the high quality of the finish, now weathering to a pleasant shade of buff.

Most original street surfaces have unfortunately been removed or overlaid with modern surfaces – there are some visible evidences of historic surfaces remaining mostly along junctions e.g. Hersham Close, Danebury Avenue and Mount Angelus Road (near the pensioners’ bungalows).

Although there remains some evidence of historic pavement surfaces, unsympathetic alterations to boundaries and the progressive loss of traditional paving materials and architectural details to modern materials, has led to some erosion of historic character. This is considered to be a negative feature of the area.

Trees and green space

For the Alton West architects, it was acknowledged from the start that the quality and scale of landscaping was a major factor in setting any approach to the layout and design of the area, this design principle made it different from that used in more typically urban sites. Downshire Field was planned to be remodelled so that there was a slight valley rising against the hill towards the north and a new copse planted in the centre of gravity of the space aiming at the feeling of aimlessness to the grass carpet; this intended spatial device has been weakened by insensitive planting, resulting in the area being peppered with trees.

By far and away the most distinctive defining characteristic of Alton West is the sheer scale and openness of the green landscape. A good place to appreciate this is the small green near the bus turning area at the junction of Danebury Avenue and Minstead Gardens. In front of Finchdean House, at 22 Danebury Avenue, still preserves a large 18th-century Lucombe oak tree, which was part of the gardens of Grove House.

To the north side, the broad sloping sweep of Downshire Field easily balances the dramatic scale of the five slab blocks on the appropriately named Highcliffe Drive. To the south side, the seven point blocks and Mount Clare sit within generous, gently sloping greens. Holybourne Avenue retains an intact stretch of Lime avenue, marking the entrance to Parkstead House (formerly Manresa House).

Even without knowing the history of the area, it is still clear that Mount Clare is an important building, set at the top of a large unbroken green area. Functionally the green is now public and available to all; visually it still appears as the setting for this splendid Georgian masterpiece. However, the more localised appearance of Mount Clare, when standing in front of it, is in a much poorer state with poorly maintained paving, which doesn’t work well with the house itself. There are many fine mature trees, legacies of the Georgian estate planting that originally defined boundaries, screened or framed views and sheltered secluded walks. Harbridge Avenue is included within the Conservation Area in recognition of the mature Lime trees that line the street, and the granite setts in which they stand.

Character Area Sub-areas:

- Western End/Schools Area

- Sherfield Gardens

- Tunworth Crescent Point Blocks

- Mount Clare and Minstead Gardens

- Downshire Field and Slabs

- Downshire House and Roehampton Lane

- Tangley Grove and Ellisfield Drive Point Blocks

- Danebury Avenue and Mayfield Convent

- Parkstead House

- Hersham Close and Eastleigh Walk

Red = Nationally listed

Orange = Positive contributor

Blue = Locally listed

White = Neutral contributor

Proposed locally listed buildings will be added to this map at a later date.

Sub Area 1: Western End/Schools Area

Townscape and Spatial Analysis

This area is characterised by its low density and green, open character. The central road, Danebury Avenue, is heavily wooded with mature trees and wide, green verges. The low density is contrasted by the use of land, which is primarily schools, and generally have boundaries of closed, secure and private character. Ibstock School, whilst being locally listed, is not particularly visible from the central public spaces. Neither the original school building nor the new, award-winning Refectory are visible. The school buildings are visible from the north of the Conservation Area, along Clarence Lane where the principal entrance gates are.

To the southern side of Danebury Avenue is Alton School, which has a long security boundary fence running along the avenue. At the western most corner of the Conservation Area is an entrance way to Richmond Park. Here, just outside the Conservation Area, is Roehampton Gate Lodge in Richmond Borough.

Architecture

Ibstock Place School is centred around, and named after, the oldest building on the site: Ibstock Place House, by Frank Chesteron in the 1910s. After early domestic owners, and requisitioning by the Ministry of Supply during WWII, the school purchased the house in 1945. The house is a good example of neo-Georgian and English vernacular revival with copious use of bricks, sash windows, steep pitched roofs and oversized chimneys. Bold red brick quoins and dressings resolve a rich and visually interesting façade. To the left of this main school building is a modern extension of around 2011, which uses limestone cladding and black glass. In its form and materiality, it fails to either complement or contrast with the locally listed building. The recent refectory, taking inspiration from the main school with its external use of brick walls and steep, tiled pitched roofs is a much more successful example of new, contextual architecture.

The architecture of the rest of the school and of Alton School is relatively modern and does not contribute nor detract from the character or appearance of the Conservation Area.

Fig. 57: Sub Area 1 map - Western End/Schools Area

Fig. 58: Mature tree down Danebury Avenue, historically the main carriageway to Mount Clare house

Fig. 59: the award winning new Refectory of Ibstock School which effectively references the surrounding context

Fig. 60: Ibstock School from the central avenue, neutral contributors to the CA

Fig. 61: The historic core of Ibstock School, locally listed

Sub Area 2: Sherfield Gardens

Townscape and Spatial Analysis

These four-storey maisonettes are part of the original Alton West masterplan and sit in two main ranges to the west of Downshire Field, in the shadow of the slab blocks. Sitting on sloping ground, running down to Danebury Avenue they have an impressive setting, which elevates their height when viewed from the avenue.

Particularly important is their relationship to the nearby slab blocks. As illustrated below; the slab blocks tower over the maisonettes creating a particularly inspiring moment. The smaller and more domestic maisonettes make the monumental blank elevations of the slabs particularly dramatic and monolithic.

Architecture

The use of the more domestic and familiar red brick intends to contrast with the concrete panels of the slab and point blocks. Instead of having the balconies open to the whole two storey house, in this typology the first floor of each house stretches across the whole width, which reduces the distinctiveness of the balcony grids like on the slab blocks. With each floor being glazed across the width, the maisonettes come across as lightweight structures with a high void to solid ratio. Panels cover the remaining solid space whilst slim brick columns break up the façade and denote the units

As the flats do not benefit from permitted development rights, there has been little change, and overall there is a strong consistency of materials and finishes. The windows have been replaced with the customary uPVC coated aluminium and these generally follow the original glazing pattern.

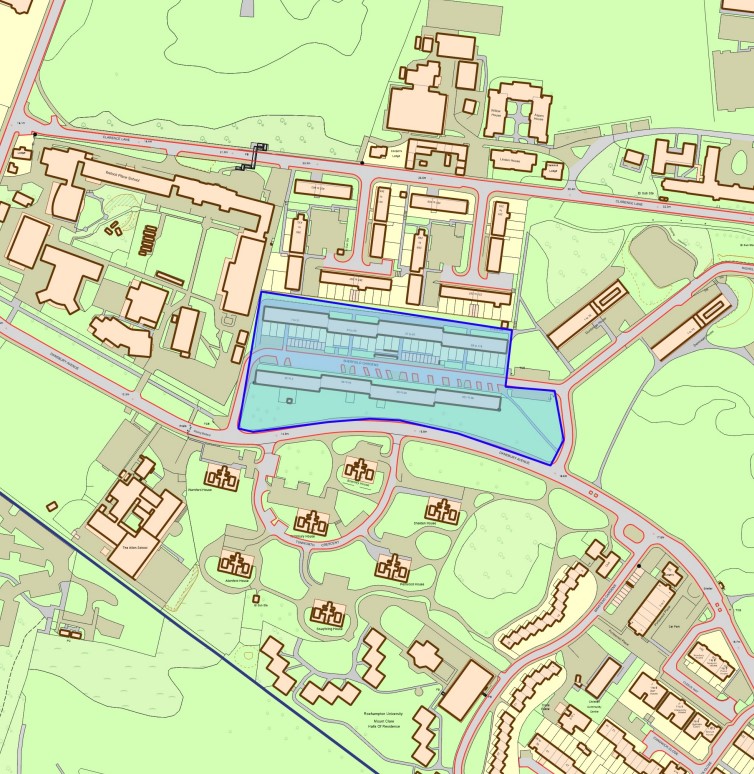

Fig. 62: Sub Area 2 map - Sherfield Gardens

Fig 63: North side, the original boundary around the gardens and the access to the maisonettes

Fig. 64: a shot further away, towards the point blocks, showing how the slab blocks change as one walks around the estate

Fig. 65: the slab blocks looming over the maisonettes showing off their contrast in scale.

Figure 66: Sherfield Gardens, north side showing the overall elevation

Sub Area 3: Tunworth Crescent Point Blocks

Townscape and Spatial Analysis

These seven point blocks at Turnworth Crescent, Warnford, Tatchbury, Allenford, Swaythling, Penwood and Shalden House, differ from those in Alton East as the balconies are recessed and instead of the white brick these use the same concrete panels of the slab blocks, keeping within the more Corbusian modern idiom. The blocks sit in the grounds of the historic Mount Clare house, which is to the south east, and opposite Sherfield Gardens.

This sub-area is entirely within the listed landscape Alton West and this area in particular was originally part of the C18 Mount Clare’s immediate grounds. The point blocks, as with the Alton East, are spaced out within a landscaped slope cut through with gently curving roads and paths. The area is heavily wooded, and the blocks are often seen behind or through trees. Cars are parked along the roads and within parking areas at the base of each block. Both the cars and the proliferation of trees greatly impact views and the experience of the landscape, and make for a much more intimate and enclosed experience rather than open views to other parts of the estate.

When walking around the blocks there are glimpsed views of the listed slabs, which tower over due to their elevated position at the top of Downshire Field.

Architecture

The twelve-storey blocks are more of a rectangular plan than in Alton East, creating two longer sides, one heavily glazed and one not, and two short sides where the solid to void ratio is greater. The stair-tower is less well detailed than in Alton East, with more obvious floor plates and less permeability.

The materials, unlike those at Alton East, are not vernacular or domestic and they match the slab blocks. The frame, including the stilts, is board-marked concrete now painted white. Like with the slabs, the elevation on stilts, a key influence from Corbusier, allows the building to sit off the ground, increasing the permeability and reducing the impact the building has on the ground. Although, the under-croft areas were cut into the landscape in order to reduce the height of the buildings overall and so unlike the slabs, which soar over the landscape, the point blocks sit low and close to ground despite the stilts. This sunken effect has caused issues with using the under-croft as they are often dark and underused, most often for bin storage.

The walls are clad with storey-height panels of prefabricated concrete, in an exact match of the slab blocks, which unifies the buildings as a singular aesthetic. Timber windows have been replaced with aluminium ones in a matching pattern.

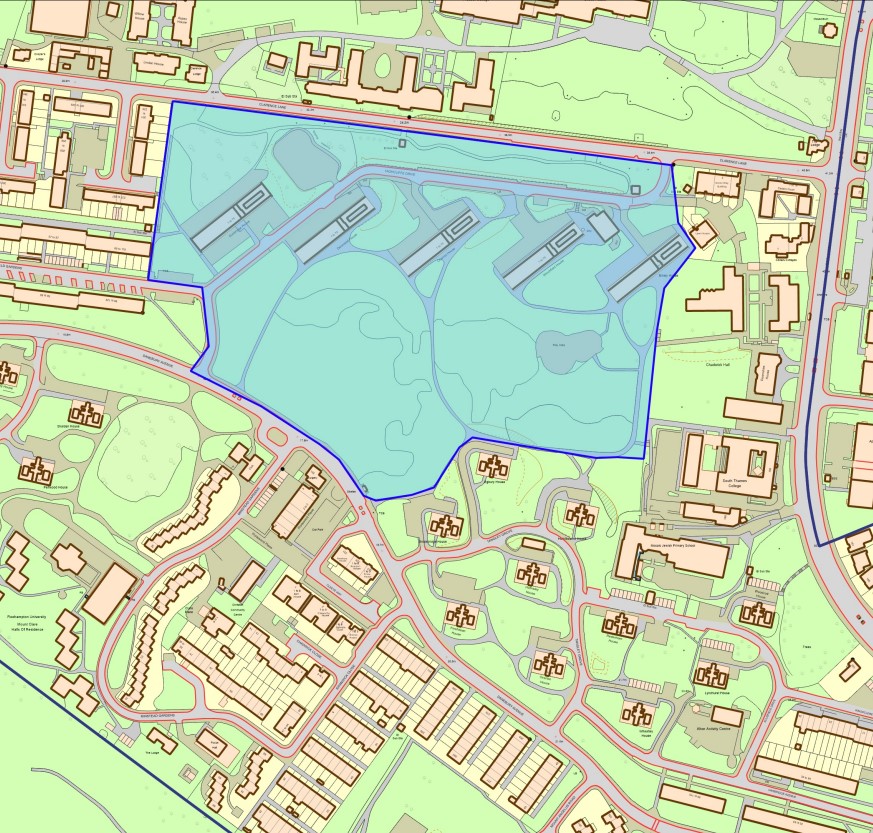

Fig. 67: Sub Area 3 map - Tunworth Crescent Point Blocks

Fig. 68: Point blocks

Fig. 69: Architectural detailing and landscape

Fig. 70: The undercroft of the ground floor which is often dark and under-used

Fig. 71: The reverse elevation which is less heavily glazed

Fig. 72: the primary glazed elevation of the blocks

Fig. 73: Point blocks and trees which often shade views across to them

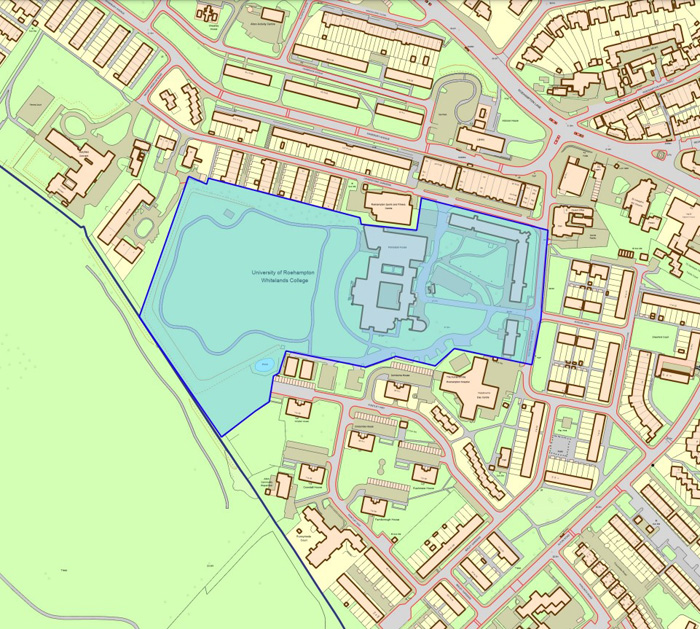

Sub Area 4: Mount Clare and Minstead Gardens

Townscape and Spatial Analysis

Mount Clare sits close to the boundary with Richmond Park (also Grade I listed) but retains a visual presence amongst the post war and recent university development. When the university took on the villa, a principal's house was built in a modernist style next to the classical Doric temple (a Georgian garden folly, listed Grade II*) which together form an interesting group of periods, styles and uses that reflects the Conservation Area's characteristic diversity. The temple was previously moved here from the grounds of Parkstead and is now on the Heritage at Risk Register due to some damage caused by vandalism following unauthorised access.

In the post-war Alton West development, Mount Clare formed a principal focal point for which the estate was designed around. Its prominent position, on an elevated position, offering views back across Downshire Field is an important aspect of its setting. Views to and from this side were a key consideration in the design and landscaping of the new housing estate. Subsequent sporadic planting of trees has greatly eroded this and now the house can only be seen at an angle to the south west of Downshire Field rather than across. This greatly reduces the visual prominence of the house and harms the experience of views when viewed from the house.

The visual contrast between the classically styled house and the concrete point blocks is a dramatic and aesthetically interesting element of the townscape. The villa, particularly due to its size and the delicacy of its detailing is the extreme contrast to the monumental blocks. The statue, which sits in front of the villa, also contrasts interestingly with the point blocks.

The immediate setting of Mount Clare is poor. The forecourt to the north east façade is standard concrete paving, often in poor condition. It does not enhance the setting nor the architecture of the house and the experience of this aspect is of an area which is largely forgotten about and not frequented with people. The setting to the rear is more successful as lawn comes all the way up to the house, improving the house’s connection with its former grand landscaping. The cedar of Lebanon, which grew adjacent to the house for over two centuries and is thought to be a remnant of plans just post-dating Capability Brown’s involvement, was recently lost. This is a great loss to the house’s setting and diminishes the appreciation of the previous landscape when in front of the house. There should be an aspiration for relevant stakeholders to restore this visual arrangement. A large hedge in front of the house, in front of a copse of trees, also diminishes any appreciation of the house’s original setting in front of a great expansive lawn, which the house would have visually dominated.

A bus-turnaround, situated around a small grassy turning circle at the end of the bungalow terrace and sitting central to Downshire Gardens, is also a negative aspect of the character and appearance. The turnaround means the street is busy with buses and the visual and landscape connection between Mount Clare and Downshire Field is impacted by the high number of buses visible within the views.

Residential student blocks developed during the occupation of the site by Garnett College, a lecturer-training college, frame the Richmond Park elevation. The small square blocks sit within the landscape and splay out and away from the house, ensuring the main elevation of the house still maintains a strong connection with views towards Richmond Park. A larger building sits adjacent to Mount Clare; this was Garnett College’s facilities building, and was also not part of the original Alton West masterplan. Whilst largely in-keeping with the modern idiom, this building introduced a large and unplanned element into a key part of the Mount Clare development and harmed the carefully planned relationship between the house and the bungalows.

The Minstead Garden bungalows, listed at Grade II in three parts (1-13, 2-26, with retaining walls, and 15-33) are part of one of the main housing types introduced by the 1950s masterplan and were intended for pensioners. This particular set of bungalows are undoubtedly situated in the most visually interesting position, forming a street out of Mount Clare’s original carriage drive, they help to frame this original route and their small size acts as a dramatic contrast to both the prominent Mount Clare on one side, and the monumental slab blocks to the other. Originally, before Garnett College removed the eastern extension of Mount Clare, the houses would have led directly up to Mount Clare itself forming a tight, intimate grouping. The preservation of the carriage drive sweep whilst also inserting new housing into the landscape is particularly successful here and is a key aspect of their significance as listed buildings and also to the Conservation Area and registered landscape.

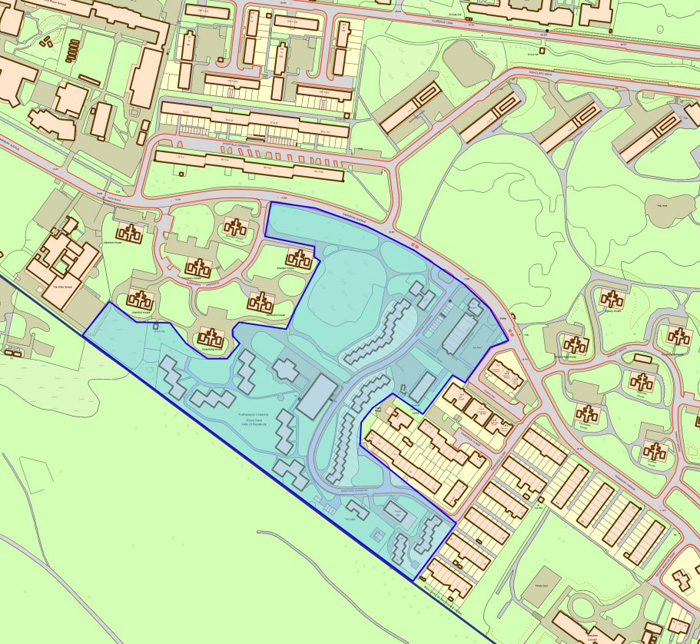

Fig. 74: Suba Area 4 map – Mount Clare and Minstead Gardens

Architecture

Mount Clare

Mount Clare (by Robert Taylor, built between 1770 and 1773, Grade I) is a Palladian villa with a rusticated lower-ground floor and stucco upper floors and a half-octagonal centre projection to the rear, a characteristic piece of Taylor’s ingenuity. Strong dentilled cornice to the parapet and pediment. The Doric order portico is a later addition by Columbani and has a balustraded terrace above. Pilasters decoratively support the portico at its rear. To the side and rear elevations on the main storey the sash windows alternate between flat and pedimented cornices. Two flights of stone steps give access to the portico and the main door. The lower-ground floor door is located centrally to the front and to the side elevations. There are distinctive semi-circular windows to this storey on all sides

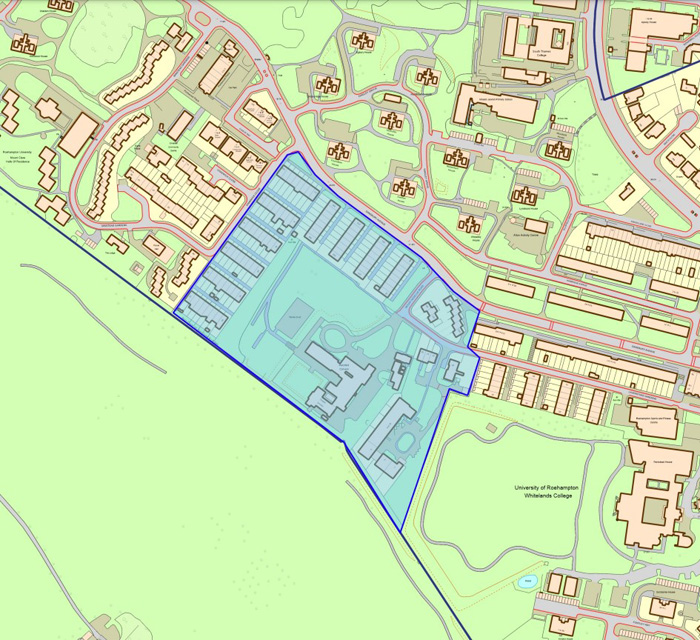

Garnett College (originally) Facilities Building and Student Blocks

After the eastern extension to Mount Clare was demolished and the overall masterplan for Alton West had been constructed, it was replaced with a large modern building to serve as Garnett College’s Facilities Building. Mount Clare itself was converted to a residence and behind it in the garden facing Richmond Park 15 square student blocks were constructed. Fanning out in two curves and flanking Mount Clare the blocks sit comfortably within the landscaped gardens. They allow Mount Clare’s view towards Richmond Park to remain, although this is now largely blocked by trees.

The blocks are not particularly interesting architecturally and do not contribute positively or negatively to the Conservation Area. Their close proximity to Mount Clare and their high number are, overall, harmful to setting of Mount Clare and to the now registered landscape.

The facilities block itself is overly large for the site and does not have any interesting visual relationship with Mount Clare or the listed bungalows below. It is overall a neutral building within the Conservation Area.

Fig. 75: the original Garnett College facilities building with side stair-case

Fig. 76: the student residential blocks and facilities building with Mount Clare in the mid-ground and the point blocks in the back-ground, demonstrating the various ways Mount Clare has lost prominence from many angles

Minstead Garden Bungalows Nos 1-33 and 2-26

Designed in 1952-3 and built in 1957-8. Staggered terraces with large communal front and rear gardens. Originally the bungalows had a very distinctive timber fence boundary treatment around the communal areas with two thick horizontal planks supported by occasional posts. Now all have been replaced with standardized metal railings. Small private areas to the front of the bungalows were bordered by low metal rube rail on dwarf timber posts. Very few of this boundary type survives. The majority of these small private areas are now mostly un-bordered and run straight into the surrounding communal grass area.

The bungalows are characterised by the simple geometry of their structure. By both being staggered and stepped, the series of brick crosswalls with flat roofs create a strong visual rhythm. Within this main-frame are recessed porches to both sides. To the front are doors next to the space for a boiler, windows to the side. Distinctive tall concrete chimney stacks complete the pleasing image of a modest countryside cottage in the modern idiom.

Fig. 77: Minstead Garden bungalows

Fig. 78: Minstead Garden bungalows with slab blocks in the background

Portswood Place

Despite being an original part of the Alton West masterplan, this short shopping arcade is not a particularly successful building. The short, straight terrace does not appear to relate in any meaningful way to either the landscape or other buildings around it. Whilst in a similar architectural style to the terraces, brick end and cross walls with heavily glazed and panelled facades, this seems less successful here in a commercial setting. The terrace now sits in a large tarmaced area, which is unpleasant and not well maintained. It is a positive building in terms of it being part of the original masterplan but its condition, setting and modest contribution to the best parts of the masterplan mean that its current contribution to the Conservation Area is neutral. To the rear is an adjoining row of low garages, which back on to Minstead Gardens. In this location these make a particularly negative contribution to the townscape and the Conservation Area, failing to address the street, presenting a solid high brick wall.

Fig. 79: Portswood Place and Danebury Surgery

Danbury Surgery