1. Adults with Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD)

1.1 Introduction

“Young people and adults with Autistic Spectrum Conditions (ASCs)

living in the London Borough of Wandsworth should be able to live

fulfilling and rewarding lives within a society that accepts and

understands them. People should be able to receive a diagnosis and any

support required. People with ASCs can depend on mainstream public

services to treat them fairly as individuals.” Wandsworth Market

Position Statement

Autism is defined as a lifelong developmental disability that affects

how people perceive the world and interact with others. Autism is

characterised by impaired social interaction and communication, severely

restricted interests and highly repetitive behaviours (see 1.2

diagnostic criteria for details). Autism can manifest in different ways

meaning people need different levels of support. Some autistic people

also have learning disabilities but autism itself is not a learning

disability. There is also a greater prevalence of some mental health and

physical health conditions amongst autistic people.

Terminology can vary and an autistic person might be described as

having:

- Autistic Spectrum Condition (ASC)

- Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

- Atypical autism

- Classic autism

- Kanner autism

- Pervasive developmental disorder

- High-functioning autism

- Asperger syndrome

- Pathological demand avoidance.

In this JSNA we use autism as a term that covers all these

diagnoses.

The evidence suggests that most self-advocates and groups of autistic

people prefer the term “ autistic person” to “person with autism” and

that is the wording that has been used in this chapter .

National strategy is governed by the Autism Act 2009 and the 2018

Think Autism Strategy Governance Refresh. The strategy has 19 objectives

under five headings:

- measuring, understanding and reporting the needs of autistic

people

- workforce development

- health, care and well-being

- specific support

- participation in the local community.

Children and young people with autistic spectrum disorders are

covered in the JSNA Start Well Chapter. There is an estimate of 1,530

adults with autism living in Wandsworth, nearly 1 in 100 of the adult

population.

This section of the JSNA looks at the barriers faced by autistic

adults in society and, where data is available, in Wandsworth in

particular. Most services focus on autistic children and young people.

However, autism is a lifelong condition and can have a significant

impact on adults. In addition, a significant number of autism diagnoses

take place in adulthood. Autistic adults with a diagnosis are entitled

to a Care Act Assessment but may not necessarily be eligible for

support. Wandsworth is in the process of developing a new local strategy

for autism that will cover all age groups.

It is important to remember autism can affect people differently. The

following sections are a generalisation and not all statements will

apply to each autistic person.

Autism is unique in being the only condition that has its own Act,

but there is no requirement to provide statutory social care services

for autistic people.

Autistic people are more likely to be:

- unemployed or under-employed

- socially isolated

- at greater risk of some physical and mental health conditions

- vulnerable to suicide

- undiagnosed, particularly if they are women, BAME or older

people

- communication impaired

- hypo or hyper-sensitive to sensory stimuli

- bullied, victims of hate crimes and exploitation

- in the Criminal Justice System.

1.2 Diagnostic Criteria

Diagnosis is the formal identification of autism, usually by a

Multidisciplinary Diagnostic Team (MDT). Although autism is a lifelong

condition and often diagnosed in childhood, there are significant

numbers of adult diagnoses. Nationally, between April to December 2018,

5,255 adults were referred for assessment where their need was suspected

autism .

Although autism is different in every person, for a diagnosis to be

made a person will usually have:

- Persistent difficulties with communication and social

interaction

- Restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviours, activities or

interests, that limit and impair everyday functioning.

Tools used for a formal diagnosis of autism vary and include:

- Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders

(DISCO)

- Autism Diagnostic Interview – Revised (ADI-R)

- Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS)

- Developmental, Dimensional and Diagnostic Interview (3Di).

1.3 Comorbidities

Some conditions are commonly diagnosed alongside autism. These

include Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Pathological

Demand Avoidance (PDA). While these are starting to be seen as potential

characteristics of autism, PDA is also seen as a diagnosis in

neurotypical people.

A learning disability is defined as a reduced intellectual ability

and difficulty with everyday activities (for example,

household tasks, socialising or managing money) which affects someone

for their whole life. Research into the overlap between autism and

learning disabilities varies in the estimation of the proportion of

autistic people who also have a learning disability. Most studies show

between 44% and 52% of autistic people may have a learning disability

and between 31% and 36% of people with a learning disability may also be

autistic .

Some physical health conditions are more prevalent amongst autistic

adults than in neurotypical adults. These include :

- immune disorders such as allergies and asthma

- metabolic disorders such as diabetes

- heart disease

- motor disorders such as cerebral palsy.

Some autistic people may avoid going to a doctor due to stress, fear

of change (especially with unfamiliar doctors) and worry about

procedures such as colonoscopies. This means diagnosis and treatment of

other conditions can be delayed which can have a long-term physical

health impact.

Studies have also found that gastrointestinal disorders are more

common amongst children with autism than the neurotypical population,

and up to a third of autistic people may experience epileptic seizures

compared to 1-2% of the neurotypical population .

Amongst autistic children, an estimated 30-60% are also diagnosed

with attention deficit disorder (ADD) or attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder (ADHD), compared to 6-7% of neurotypical children. Autism can

disrupt sleep for children and adults .

Some Common Mental Disorders (CMD) can be prominent amongst autistic

people. 40% of autistic people have symptoms of at least one anxiety

disorder compared to 15% of the neurotypical population. This is often

combined with depression. A combination of factors that lead to

vulnerability to stress include:

- biological differences in brain structure

- history of social difficulties including decreased self-esteem and

an overestimation of threats

- problems finding flexible responses to change and apparent

threats.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is also more common in autistic

people. This is thought to be because of a combination of genetic

factors and psychological predisposition. Diagnosis of OCD in autistic

people is difficult because it may be mistaken for repetitive

behaviour.

It is estimated 20% of the population will experience a period of

depression in their lifetime, this is more common in autistic people.

They can also find it harder to seek help for depression because change

can be daunting and raise anxiety levels. It can be difficult for them

to explain their feelings, symptoms, and concerns.

1.3 Prevalence and the Level of Need in the Population

There are around 700,000 people with autism in the UK, more than 1 in

every 100 of the population.

The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS) included a measure for

autism for the first time in 2007. It showed 1% of the adult population

had autism (decreasing by age from 1.1% aged 16-44 to 0.8% aged 75+).

The Department of Health funded a project to build on this study and

found that the actual prevalence was closer to 1.1% of the population.

The APMS carried out in 2014 showed a prevalence of between 0.5% and

1.3% of the population – the large range is due to the low prevalence

combined with the size of the sample.

There is no register of adults with autism. However, in Wandsworth

there are 737 children with a diagnosis of autism known to schools,

approximately 1.65% of the population. This is higher than the London

average of 1.5%, and England average of 1.37%. The lower prevalence in

adults found in the APMS is probably due to:

- an increase in diagnosis over time, either due to an increased

prevalence of the condition or better diagnostic criteria now compared

to the 1970s and 80s

- lower life expectancy for autistic people.

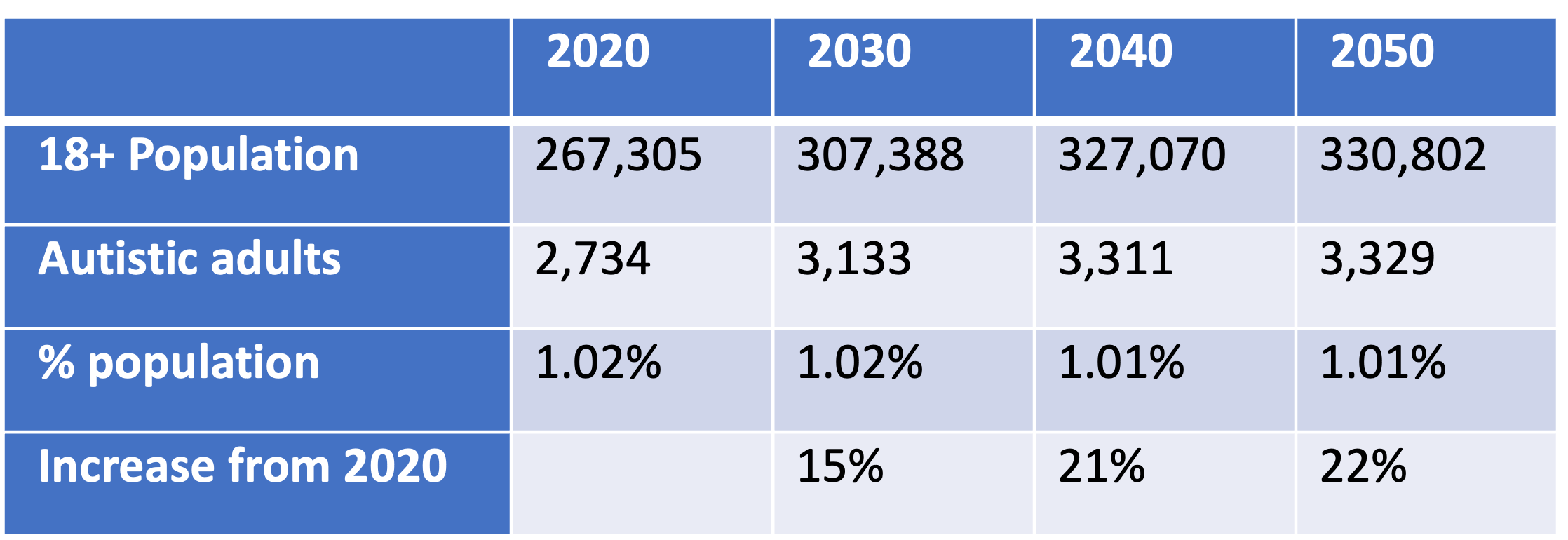

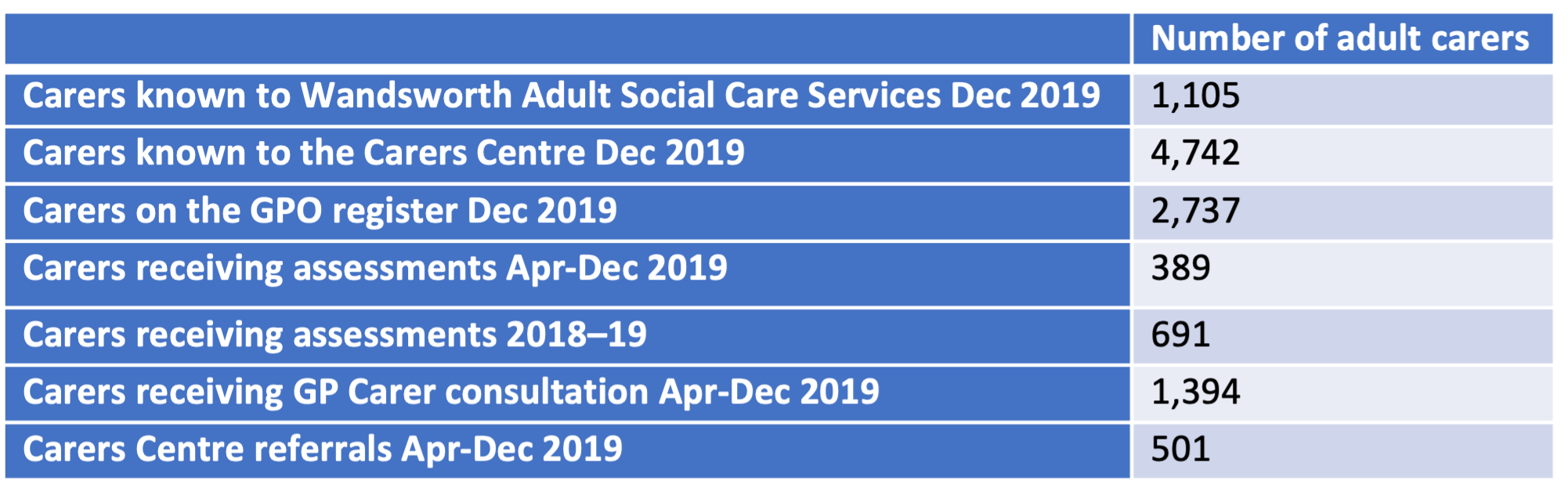

Using age-related national prevalence rates based on a total national

population of 1%, it is estimated that the number of people in

Wandsworth with autism in 2020 is approximately 2,700, 1.02% of

Wandsworth’s population. The table below assumes that the percentage of

the population with autism remains steady.

Estimated number of autistic people in

Wandsworth

Source: GLA population estimates & Office of National Statistics

(2016)

Most new diagnoses of autism occur in children. However, because of

improved diagnostic criteria and an increase in awareness, more adults

are being diagnosed. Nationally 17,975 new referrals for

suspected autism were made between April and December 2018. 70% of these

were children and 5,255 were adults. If this rate is consistent it would

suggest that nationally, approximately 7,000 adults will be referred for

a new autism diagnosis. 64% of all referrals were men and boys. (The

data does not show how many people received a diagnosis).

Autism is not regarded as a social care need. However, there are some

people with a social care need who also have autism. In 2017-18, there

were 87 new assessments in Wandsworth Adult Social Care for autistic

people:

- 52 had a learning disability

- 15 had a mental health need.

1.4 Current Services

While providing a social care assessment is a statutory requirement,

unless autistic people have other needs such as learning disabilities,

it is unlikely that they will be eligible for statutory social care

support. Most support services designed for autistic people are

non-statutory. In Wandsworth, work is underway as part of the refresh of

the Autism Strategy, to review services and develop actions to improve

the experience of autistic people in accessing local autism

services.

The Wandsworth Autism Advisory Service (WAAS) is a multi-professional

team that supports schools, organisations and families in Wandsworth to

achieve the best possible outcomes for autistic children and young

people. The service supports education establishments to enable all

children with autism and social communication disorders to achieve their

full potential.

WAAS offers a service which is available to all Wandsworth residents

with a child or young person with a diagnosis of autism, Wandsworth

schools, early years settings, services and professionals. The service

also provides a more specialist and targeted offer which is accessed

through referral to the service.

The WAAS works closely with partners across Wandsworth to provide a

planned and graduated support for parents and families who have a child

with autism (and those on the specialist pathway). The service provides

a point of contact for specialist advice and support. It aims to

up-skill families through a bespoke parent / carer training programme.

Parent support is available to all Wandsworth residents regardless of

the child/ young person’s educational placement. Up to date details of

the parent offer can be found on the Wandsworth Local Offer.

Choice Support is commissioned by the Council to provide employment

support for autistic people, with or without a learning disability. The

service includes support in obtaining and maintaining employment,

working both with the individual and their employer.

The National Autistic Society provides support and guidance for

adults and children with autism, and their families. Their “Autism at

Work” service works with employers to support autistic people in the

workplace .

1.5 Predictive Factors

Autism is a lifelong condition that affects 1.1% of the population .

Despite this relatively high prevalence, the causes are still largely

unknown. Factors that can increase the likelihood of a diagnosis of

autism include:

- an autistic sibling

- older parents

- certain genetic conditions

- very low birth weight

- some maternal metabolic conditions.

It is probable there are genetic factors responsible for some forms

of autism. It is more likely to have multiple genes and an interaction

with environmental factors rather than a single genetic cause.

Identifying a predisposition to autism through genetic testing is,

therefore, not possible .

1.6 Related Effects of Autism

Autism and communication Autistic people have difficulties with

interpreting both verbal and non-verbal language. They may find it

particularly difficult to understand:

- facial expressions

- tone of voice

- jokes and sarcasm.

Some autistic people may not speak or may have limited speech. They

will often understand more of what is said to them than they are able to

express and may struggle with abstract concepts. Some autistic people

benefit from using sign language or visual symbols instead of speech.

Others may have good language skills but struggle to understand the

expectation of others within conversations. This can manifest itself in

a number of ways including repeating what the other person has said or

talking at length about their own interests .

Sometimes a diagnosis of auditory processing disorder can occur

alongside autism. This condition impairs the ability of the person to

understand what they hear and convert it into meaning. This condition

can also occur separately to autism, there is currently no definitive

understanding of how the two conditions are linked .

Eye contact can be hard for some autistic people to the point of

causing physical pain if forced. This can often make normal social

interactions difficult .

Autistic people can find it hard to decode everyday speech,

especially when the person talking is using sarcasm, “kind lies” or

“half-truths”. This inability to see subtext in a conversation can make

autistic people vulnerable to exploitation, especially when friendship

is being offered .

Masking is a behaviour where autistic people will try to imitate

neurotypical behaviour in order to avoid social stigma. However, this

can cause autistic people intense strain which can make coping harder .

“Information overload” is a familiar term when talking about email

communications and social media. However, autistic people will often

experience this in everyday life. If there is too much information

(including sensory information) some autistic people can be distressed

and shut down, unable to interact further. Some autistic people can use

“pre-intentional” communication, talking to themselves to help them keep

calm and focussed, or as a reaction to an exciting or distressing

situation .

These communication difficulties mean that many autistic people

can:

- appear to be insensitive

- seek out time alone when overloaded

- fail to seek comfort, help or support from other people

- appear to behave strangely or inappropriately

- become physically or verbally aggressive towards themselves or

others when overwhelmed

- retreat into themselves and be unresponsive.

Failure to recognise the communication needs of autistic people can

exacerbate the communication barrier and lead to autistic people

shutting down or being labelled as having challenging behaviour.

Sensory Differences

Some autistic people process sensory information differently to

neurotypical people. This can vary from person to person, from sense to

sense, and be either over or under sensitive to different inputs . For

example:

- an oversensitivity to touch might cause someone to feel a seam in an

article of clothing as not only uncomfortable but giving them

overwhelming pain

- an under-sensitivity to sound may mean that someone is unable to

even recognise someone talking to them without extreme effort to

concentrate. However, an oversensitivity to sound may mean that someone

is overwhelmed and unable to function because of a background noise

which a neurotypical person may not even notice.

Sometimes sensory differences means autistic people might be obsessed

with certain patterns, shapes, colours, sounds and sensations. This can

lead to compulsively touching people and objects or making obsessive

sounds.

This over and under sensitivity to sensory input can manifest in all

or just some of the senses, each person will be affected

differently.

Autism and Patterns of Behaviour

Autistic people can find the world confusing and overwhelming. Often,

they prefer a regular daily routine so that they know what is going to

happen, and a set of rules that they can follow without variation. They

can find changes upsetting, especially if they are unexpected .

Many autistic people have intense or highly focussed interests. These

can change and develop over time but tend to be lifelong. This can often

be channelled into studying, work, volunteering or other meaningful

occupation, and can be fundamental to their well-being.

Some autistic people will use self-stimulating repetitive behaviours

such as fiddling with an object or rocking . This is thought to be a way

of imposing some control over intense emotions and thoughts.

Autism and Life Expectancy

A Swedish Study Hirvikoski (2018) showed the average

age of death for an autistic person is 58 years for those without a

learning disability and 39.5 years for those with a learning disability,

compared with an age standardised general population age of 70. Leading

causes of death were found to be neurological disorders such as epilepsy

(which has previously been linked to autism) and suicide. People with

high-functioning disorders have a nine-fold suicide risk compared to the

neurotypical population.

An American Study in 2017 found the life expectancy for autistic

people to be 36 years old compared to 72 years for the general

population. It found 28% died due to an injury including suffocation,

asphyxiation and drowning. This study looked primarily at

lower-functioning disorders.

Autism and Employment

There is a significant employment gap for autistic people when all

disabilities are considered :

- 80% of people are in full or part time paid employment

- 47% of people with disabilities are in full or part time paid

employment

- 32% of autistic people are in full or part time paid

employment.

Only 16% of autistic adults are in full-time paid employment. This

figure has remained steady since 2007. In addition, 77% of those who are

not employed say that they would like a job, and 25% of those employed

part time would like to work more hours. 51% of autistic people in

employment reported that they had skill levels higher than their job

requires .

When autistic people are in work, 48% have experienced bullying or

harassment in their workplace. Only 58% have disclosed their autism.

Where people have disclosed their autism, only 32% were asked what

adjustments they would need in the workplace .

Barriers to employment for autistic people include :

- The interview and application process: One of the defining

characteristics of autism is communication difficulties. An autistic

person might need more time to formulate their answers to interview

questions, or may have difficulties coping with the interview

process

- The work environment: Since many autistic people have sensory

sensitivities, a work environment that is noisy, brightly lit or busy

can be overwhelming. 35% of people who had disclosed their autism to

employers said that the adjustments made were poor

- Lack of employer understanding about autism: 60% of employers stated

that they do not know where to go for support or advice about employees

with autism, 60% said they would worry about getting the support they

offered to an employee wrong, and 40% believed it would cost them more

to employ someone with autism.

Autism and Social Isolation

The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey in 2007 showed the

prevalence of autism was higher amongst single respondents than married

people. Research in America has shown that only 5% of autistic adults

marry and 67% have no interest in romantic relationships. While the

participants for this study were more likely to be on the lower

functioning end of the spectrum (most of the participants were diagnosed

in the 1970s/80s when the criteria was stricter), the results do suggest

that autistic adults are less likely to form romantic relationships.

Many autistic people find it hard to form friendships, even when they

want to. Understanding and communicating with other people is

particularly difficult and can leave autistic people feeling lonely. As

many as 79% of autistic people, and 70% of their families, feel socially

isolated. 81% say they feel lonely some of the time because of autism

related anxiety rel. 81% of young autistic people believe they spend

less time socialising than their peers .

Some of the factors that impact on social isolation include :

- struggles in social situations

- autism as a hidden disability and can be misunderstood by people

around them

- prevalence for anxiety and depression can cause loneliness and

social isolation

- the employment gap for those with autism limits the opportunities to

make connections with other people

- 70% of autistic adults feel that they need more support to reduce

social isolation.

Transition

At ages 16-25 young autistic people have challenges due to the impact

of sudden change in their lives. Change may include:

- moving from a structured school environment to more self-directed

learning, employment or unemployment

- adjusting to changing friendship groups and building adult

relationships

- changes in or lack of support.

Criminal Justice System

Not only are autistic people vulnerable to exploitation, bullying and

hate crime, there is evidence autistic people are overrepresented in the

Criminal Justice System. This is thought to be due to :

- susceptibility to influence, exploitation and manipulation

- inability to think beyond the immediate impact of an action

- difficulties expressing thoughts and emotions leading to a physical

response to frustration.

Autism and Gender

More men are diagnosed with autism than women. The condition can

often manifest itself in different ways by gender. Various studies have

shown the ratio of male to female autistic people varies significantly.

A 2009 survey of adults living in households throughout England found

that 1.8% of men and boys had an autism diagnosis compared to 0.2% of

women and girls. A 2017 study showed a male to female ratio of

approximately 3:1. A study of people with a learning disability and

autism showed a ratio closer to 2:1 .

The male and female ratio has been challenged and there are a number

of theories to explain the gender differences. These include :

- girls and women with autism have characteristics that do not fit the

profile usually associated with men and boys (diagnostic tools are based

on characteristics found in groups of males)

- bias from practitioners who see autism as primarily a male

condition

- autism is an exaggeration of normal gender differences

- the effects of foetal testosterone on brain development are a causal

factor in autism

- a range of biological factors may mean men and boys have a higher

prevalence

- women and girls on the higher-functioning end of the autistic

spectrum may be better at masking their traits

- autism traits in girls are underreported in schools.

Autism Diagnosis Post-childhood

While autism diagnosis in children has improved, there have also been

more adult diagnoses in recent years. Current knowledge of older people

and autism is limited. Under-diagnosis may lead to a lack of support for

managing the impact of their condition such as social isolation at home,

or in accommodation-based care .

The lower life expectancy for adults with autism distort prevalence

rates. Autistic people without a diagnosis and the corresponding

support, are at a higher risk of life reducing mental health

conditions.

1.8 Diagnosis and Identification

Estimated numbers of autistic people in the population are subject to

a large margin of error. Studies to determine population prevalence give

varied results dependent on the criteria used. Diagnostic criteria has

evolved as a greater understanding of autism has been developed. While

increasing numbers of people are diagnosed in childhood, there are still

several autistic people who receive a diagnosis in adulthood or who have

not been diagnosed and are unable to access appropriate support

services. Current knowledge of older people and autism is limited .

There are two suspected under diagnosed groups:

- Women and Girls: More men are diagnosed with autism than women and

the condition can often manifest itself in different ways by gender.

There are a number of theories to explain the gender split but there is

no conclusive evidence the split is due to genetic factors (i.e., men

more likely to be autistic), or social and diagnostic factors (i.e.,

women less likely to be diagnosed)

- BAME Groups: Evidence suggests BAME children and adults can

experience difficulties with obtaining a diagnosis of autism, and more

likely to be diagnosed incorrectly with other conditions .

Services and Support

Autistic people experience many barriers to day-to-day living, and

because autism is a hidden disability these are not always known,

understood or acknowledged.

Communication difficulties mean that many autistic people can:

- appear to be insensitive

- seek out time alone when overloaded

- fail to seek comfort, help or support from other people

- appear to behave strangely or inappropriately

- become physically or verbally aggressive towards themselves or

others when overwhelmed

- retreat into themselves and be unresponsive.

Many autistic people react negatively to change. They prefer a

regular daily routine so that they know what is going to happen, and a

set of rules that they can follow without variation. Unexpected changes

can be debilitating, and they take more time to adapt to the new

situation.

There is a significant employment gap for autistic people, more than

when all disabilities are considered. Only 16% of autistic adults are in

full-time paid employment, 32% are in paid employment.

Many autistic people find it hard to form friendships, autistic

adults are less likely to form romantic relationships. As many as 79% of

autistic people and 70% of their families feel socially isolated.

Health

Some physical health conditions are more prevalent amongst autistic

adults than in neurotypical adults . These include:

- immune disorders such as allergies and asthma

- metabolic disorders such as diabetes

- heart disease

- motor disorders such as cerebral palsy.

Some Common Mental Disorders (CMD) are also more prevalent amongst

autistic adults:

- 40% of autistic people have symptoms of at least one anxiety

disorder compared with 15% of the neurotypical population

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is more common in autistic

people

- depression is often linked with anxiety.

Some people with may avoid going to a doctor due to stress, fear of

change, and worry about procedures. They can also find it harder to seek

help for CMD because change can be daunting and raise anxiety levels.

They can also find it difficult to describe their feelings, making it

hard to communicate symptoms and concerns.

Studies show people with high-functioning disorders have a nine-fold

suicide risk compared to the neurotypical population. It is a leading

cause of the reduced life expectancy for autistic people.

1.9 Interventions/Approaches According to the Evidence Base

Several weaknesses that have been identified with the current

evidence base for the support needs autistic adults. This is partly due

to the lack of services specifically for adults as they are often not

eligible for social care support. If they have another condition, such

as a learning disability or mental health condition, care is focused on

that condition.

The National Institute for Clinical Evidence guidelines recommend

psychosocial interventions rather than medication. There has been no

convincing evidence that medication is effective in managing autism .

Applied behaviour analysis, although a common treatment, has been

heavily criticised because it seeks to impose neurotypical behaviours on

autistic people. A strength-based approach has been shown to be more

effective because it works with the positives autism brings to people’s

lives, especially their individual strengths.

A good understanding of autism is required to design and deliver

support services tailored to individual need. This can be a challenge

because people have a variety of characteristics. Autism training for

front-line staff has been found to have a positive impact on people’s

experience of services and autism friendly environments.

Research has found social skills training may be effective for in the

reduction of depression, anxiety and inappropriate social behaviour.

However most existing training is aimed at young adults and it is

unknown whether the value for adults aged 30+ would be the same .

Services that provide general support for independent living have

proven successful. Peer support groups are another valued service and

provide autistic people opportunities for social interaction and sharing

experiences.

A multidisciplinary approach can reduce service costs, increase

diagnosis rates, reduce crisis interventions, and improve employment

rates.

2. Physical and Sensory Disabilities

2.1 Introduction

Physical and sensory impairments affect people across all ages of the

life course. Impairments can be caused by a condition, injury or the

result of ageing. Some may present from birth or can be sustained after

a life-changing event. These impairments can be a great challenge for

those in a world designed for able-bodied people. Depending on the

impairment, a person may have issues with transport, access, and

communication. The government has prioritised all disabilities through

the Equality Act 2010 . However, further progress is required to

improves the lives of disabled people:

“All people should have the opportunity to be active citizens; live a

meaningful life and make positive contributions to the community they

are part of. People with a Physical or Sensory Impairment have the same

aspirations as everyone else. They would like to be independent, have a

job, have their own home, make and keep friends, form relationships and

choose what they do in their spare time. People with physical and

sensory disabilities should be recognised as equal and enjoy the same

life opportunities as others. We want services in our Borough that

actively work with people to define their goals and achieve them;

services that consider the whole of a person’s life and to work with

providers that are aware of varied areas of provision and make links

across the care landscape.”

Wandsworth Market Position Statement

Defining disability is complex and contentious. The ‘social model of

disability’ states people with disabilities encounter barriers in

society including the environment, people’s attitudes and organisations.

The ‘medical model’ is based on a belief that disability is caused by an

individual’s health condition or impairment .

Examples of definitions include:

- The Equality Act 2010 defines disability as having a physical or

mental impairment that has a substantial and long-term negative effect

on the ability to do normal daily activities. Long-term is defined in

the guidance in terms of at least 12 months

- The World Health Organisation states that a disability “is an

umbrella term, covering impairments, activity limitations, and

participation restrictions. An impairment is a problem in body function

or structure; an activity limitation is a difficulty encountered by an

individual in executing a task or action; while a participation

restriction is a problem experienced by an individual in involvement in

life situations.”

For the purposes of this chapter, we are defining physical and

sensory disabilities as “a physical, mobility or sensory condition that

causes a person to face barriers in undertaking day to day tasks”. This

fits with the national reporting model for social care which groups

people by their primary support reason (PSR).

The social care Primary Support Reasons (PSRs) covered in this

section are:

- physical support: mobility need

- physical support: personal care need

- sensory support: visual impairment

- sensory support: hearing impairment

- sensory support: dual impairment

Key UK legislation includes: * The Equality Act 2010 which is the

UK’s legal framework designed to protect disabled people from

discrimination . * The Care Act 2014 which is the UK’s

legal framework for Local Authority provision for adults with care and

support needs under the principle of promoting wellbeing which includes

:

- personal dignity

- physical and mental health and emotional wellbeing

- protection from abuse and neglect

- control by the individual over day-to-day life

- participation in work, education, training or recreation

- social and economic wellbeing

- domestic, family and personal

- suitability of living accommodation

- contribution to society.

Physical and sensory disabilities become more prevalent with age,

along with other long-term conditions, such as diabetes and may impact

on mobility and personal care requirements. The average age of the adult

disabled person in London is 43.7 years compared to average of 37.5

years for people without disabilities. Preventative support at a younger

age may delay, reduce or entirely prevent the onset of further

conditions or reduce deterioration .

An estimated 30% of people with a long-term physical health condition

also experience mental health problems, most commonly depression and

anxiety, which can be exacerbated by social isolation. This can lead to

significantly poorer health outcomes and a reduced quality of life. It

is estimated that mental health problems increase the cost of NHS

treatment of limiting long term physical health conditions by an

additional £8,000 million to £13,000 million annually. The lowest

estimate equates to £1 in every £8 spent on limiting long term physical

health conditions .

Barriers

People with physical and sensory disabilities face several barriers.

These include :

- stigma surrounding disabilities and negative experiences can become

a barrier to accessing support services

- opportunities to make and sustain social contacts can be limited and

lead to isolation and loneliness

- sighted-guides and communicator-guides are often difficult to

obtain, and there is some difficulty in getting requests through the

locality teams due to lack of sensory knowledge

- barriers to employment mean that people with physical and sensory

disabilities are less likely to be employed, or be employed for fewer

hours and lower hourly pay, than other people with equivalent skills and

experience

- On average, a person with a disability spends 47% more on the costs

of day-to-day living

Wandsworth is committed to working with communities and local

organisations to reduce the impact of these barriers.

2.2 Prevalence and Level of Need in the Population

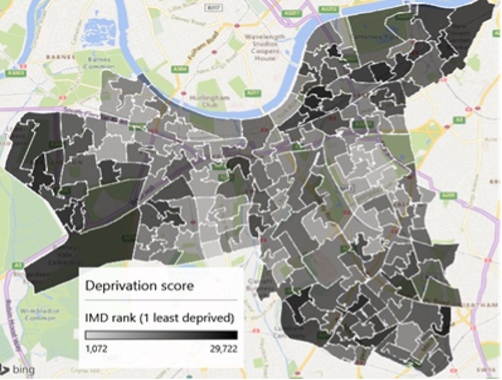

Using 2020 local prevalence rates, it is estimated there are over

46,300 people aged 18-64 (6.4%) whose ability to do day to day tasks is

limited by long-term condition or illness including physical, sensory,

learning disabilities and mental health conditions. Over 19,800 state

they are significantly limited.

Applying national age-related prevalence rates to Wandsworth 18-64

population it is estimated:

- 4.1% (22,000) mobility impairments

- 0.8% (4,200) visual impairments

- 0.5% (2,800) severe hearing loss

- 7.8% (41,600) some hearing loss.

All these numbers are expected to increase over the next 30 years as

presented in the table below.

Estimates of the number of people with

disabilities in Wandsworth

Source: GLA population estimates; Deloitte Access Economics (2017)

and Office for Disability Issues, (2011b)

However, these are based on national age-related prevalence rates and

because of current and historical good services for hearing impaired

people in Wandsworth, the actual numbers of this group may be higher,

particularly in younger people with profound hearing impairments.

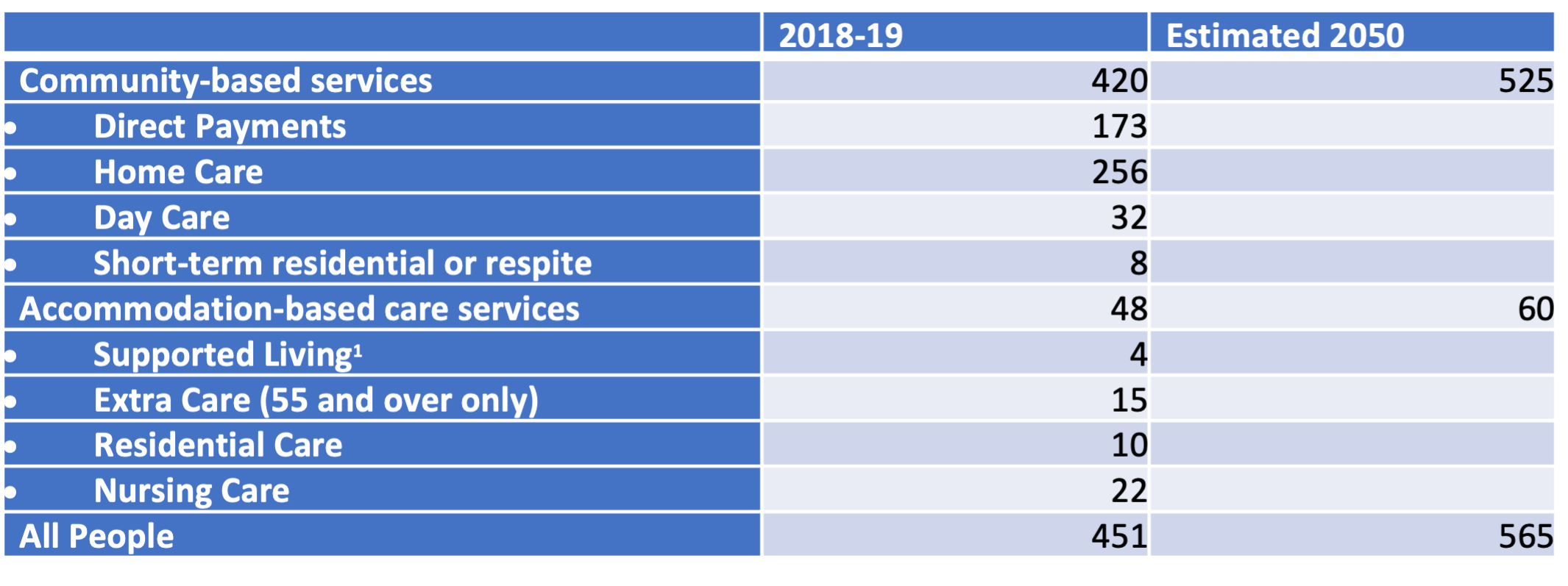

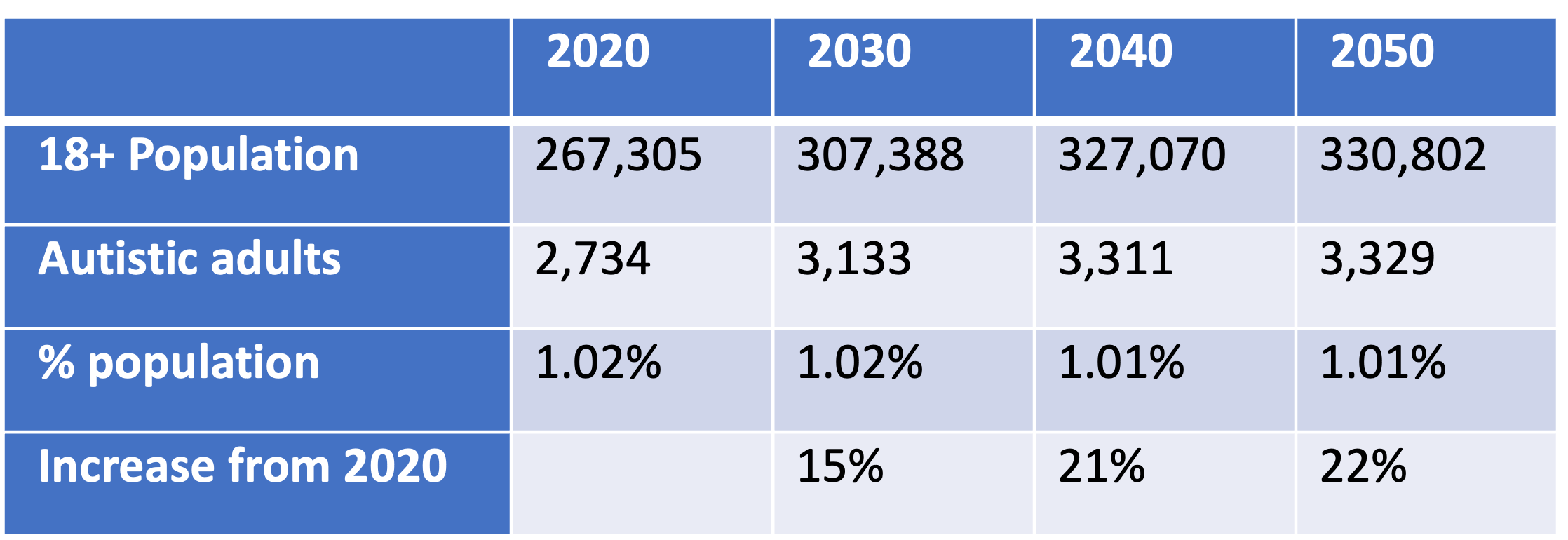

In 2018-19, there were a total of 451 adults aged 18-64 receiving

social care services in Wandsworth for physical health and sensory

needs, the table below.

People receiving social care services in

Wandsworth with physical and sensory needs

Source: internal data

The proportion of people in this group receiving direct payments is

41%. While there is no specific benchmarking data for this group, the

overall proportion of people aged 18-64 receiving their community-based

services through direct payment is 28%, slightly lower than the England

(31%) and London (29%) averages.

Out of the 451 people, 97% had a physical impairment. 21% needed

mobility assistance only, and 75% required mobility and personal care

support. An increase of 25% was used to estimate need by 2050. Due to

the small numbers involved, the projections have a large margin of

error. Within this group, an increase in social care need is anticipated

and subject to change with unexpected external factors.

The proportion of the 18-64 year olds with mobility, visual and

hearing impairments is expected to increase by 2050. It is unknown how

the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic will have in terms of increasing the

number of people with long-term ill health or receiving social care

services. The projections and analysis of future trends is therefore

subject to significant margins of error. Much of the other data are

extrapolated from national prevalence rates. The estimates are based on

the age of Wandsworth’s population but not the specific socio-economic

profile of the Borough. Some people are reluctant to identify themselves

as disabled due to the potential stigma or prejudice. Others may be

deterred from formal services due to access difficulties (e.g., booking

appointments via a telephone system).

2.3 Current Services on Offer

Within the legislative framework Wandsworth has a duty to promote

wellbeing and ensure equality of opportunity for people with

disabilities. People with physical and sensory disabilities often face

barriers to undertaking day to day tasks which may require equipment,

adaptation and support, or social and cultural change within

communities. The national agenda for personalisation means putting

individuals strengths and preferences at the centre of their care.

Wandsworth follows a strength-based approach focussing on the abilities

of the individual rather than their disabilities in order to overcome

barriers and find solutions.

The Council continues to promote Direct Payment uptake to support

choice and control and expects providers to continue to offer and

develop a wider range of personalised and bespoke services. Currently

14% of this cohort are choosing to use this option to direct their own

care.

Where a person with eligible social care needs chooses not to manage

their own care through a Direct Payment, Wandsworth organises

appropriate community-based services such as homecare and day care.

Housing and Accommodation

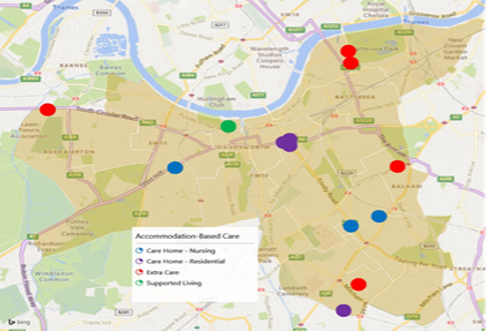

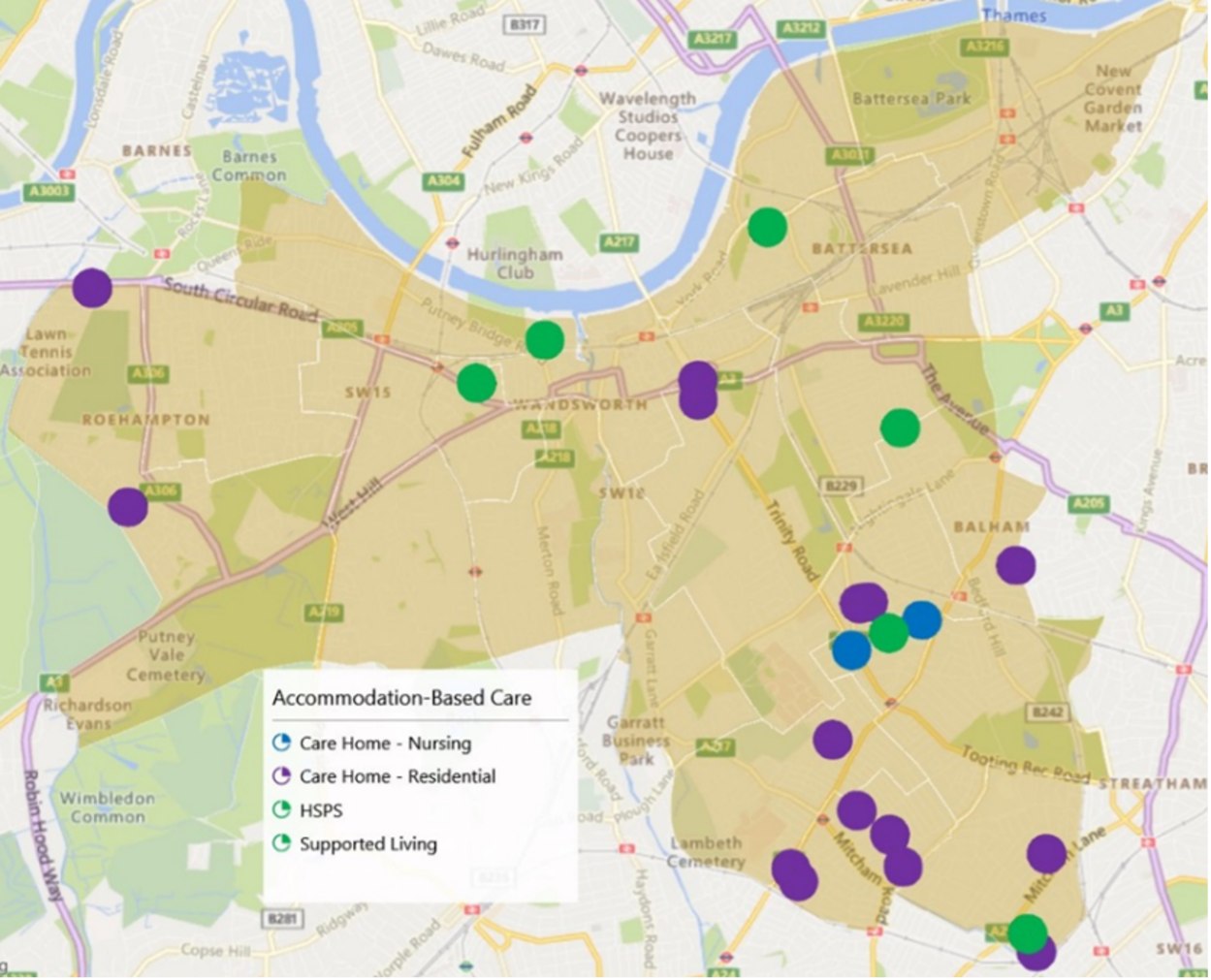

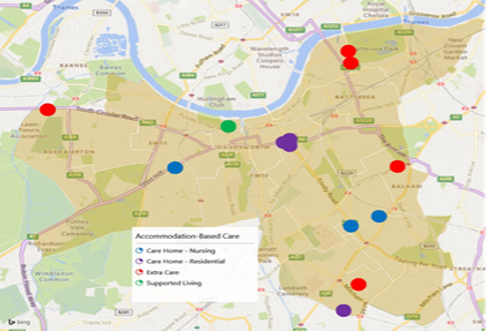

There are no accommodation-based services that specifically cater for

this group in Wandsworth. However, there are four residential and three

nursing homes that will take working age adults with physical and

sensory disabilities. While recent admission figures are low for this

group, evidence is that Out of Borough Placements are used to ensure

people are placed in appropriate accommodation for their specific needs.

There are five Extra Care Housing Schemes that accept people from age

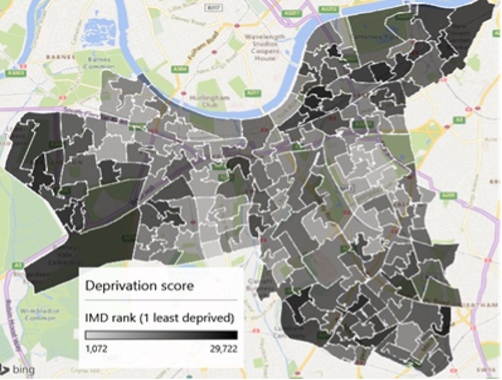

55+ (the figure below). Three of these schemes are commissioned by

Wandsworth Council and the other two are privately run.

A recent analysis of accommodation-based care needs suggested that

there may be a need for some locally based supported living

accommodation such as extra care provision for younger adults. This was

due to all current placements being out of Borough. However, the

conclusion was there was insufficient evidence for this need and further

work is to be to be undertaken to inform decisions.

There is a Sensory Impairment Service in Wandsworth which provides

services to visually impaired people including advice, equipment and

training. Facilities at Liden Lodge School include Wandsworth Hearing

Support and Vision Support Services. Voiceability Wandsworth is

commissioned by the Council to support sensory disabilities, and Blind

Aid provides support for reading and responding to mail.

Location of accommodation-based care services in

Wandsworth

Source: internal data

2.3 Disability Prejudice, Social Isolation and Loneliness

Some of the barriers disabled people face involve lack of

opportunities to make and sustain social contacts, leading to isolation

and loneliness. This includes people with diverse impairments and

personal circumstances. The barriers that people face include :

- physical barriers such as limited access to social and community

groups for someone with mobility issues or visual impairment

- communication barriers such as those faced by people with hearing

impairments

- a national survey of people without disabilities 49% stated that

they did not have anything in common with disabled people, 26% admitting

that they have avoided engaging in conversation with a disabled

person

- one in three disabled people in a national survey feel that there is

a lot of prejudice against people with disabilities, another half feel

there is some prejudice. When the same question was asked of people

without disabilities, only one in five stated there was a lot of

prejudice

These barriers have a tremendous impact on the welfare and quality of

life of disabled people .

- 53% from a national survey reported feeling lonely regularly, 23%

saying they will feel lonely on any typical day

- 14% of people with a visual impairment say they never or rarely have

as much social contact as they like, and feel very or completely cut off

from people

- 30% of people with mobility issues say they are always or often

lonely

- 74% of people with an Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) say their social

life has been affected as a result of their impairment

- 22% of people living with cancer are affected by loneliness.

Loneliness and social isolation are known to negatively impact both

on emotional, mental and physical. Weak social connections can be as

harmful to physical health as smoking 15 cigarettes a day. Lonely

individuals are at a higher risk of increasing disability.

2.4 Employment/ Income and Cost of Living

The Care Act 2014 demands that Local Authorities provide support and

services in a way that promotes individual choice and improved

wellbeing. For disabled people, improving access to mainstream services,

education and employment, will lead to better health, social and

economic outcomes as the person is able to live a more connected and

meaningful life.

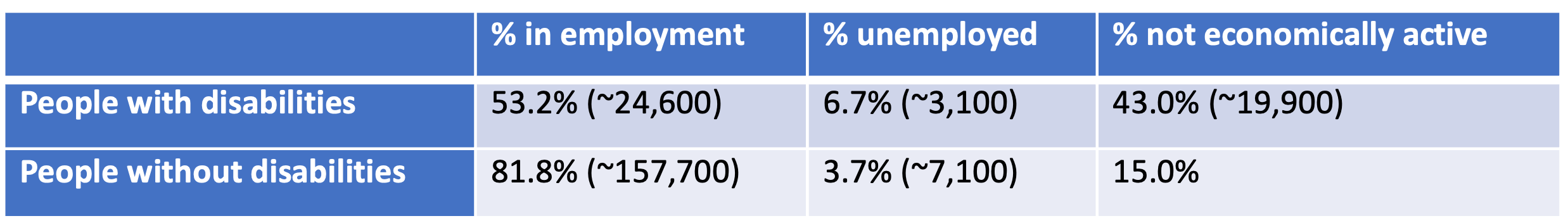

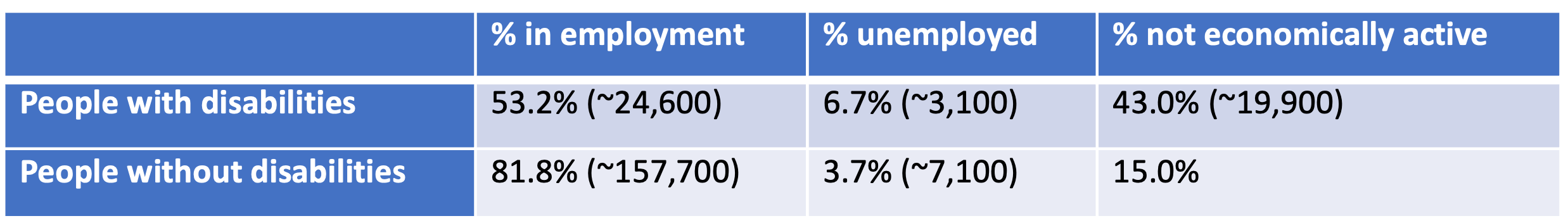

There is a significant difference in economic activity and employment

rates between people with and without disabilities . The national

estimates have been applied to the Wandsworth figures in the table

below.

Comparison of estimated economic activity of

people with and without disabilities in Wandsworth

Source: House of Commons Library, 2020.

When people with disabilities are in employment, they are more likely

(34% compared to 23%) to be working part time .

Median pay is significantly lower for people with disabilities,

earning an average of 12.2% less per hour than people without

disabilities. The disability pay gap is wider in London than any other

area of the country, at 15.3% less being paid to people with

disabilities. Nationally, the pay gap for people with disabilities

employed as managers, directors or senior officials is the largest, at

13.1%. In addition the pay gap was largest for people aged 30-49 .

Life costs more for people with disabilities and their families who

have to spend, on average, an estimated 47% more than people without

disabilities (equivalent to a national average £585 extra per month).

One in five disabled people face extra costs of over £1,000 a month .

3. Learning Disabilities

3.1 Introduction

The focus of the commissioning model for learning disability services

is to reduce reliance on residential care. Service users are provided

with supported living and greater independence where possible, with

fewer out of Borough placements. In addition, the Council encourages the

provision of meaningful daytime activities and life skill development

opportunities with stronger pathways towards a measurable outcome. There

is a drive to develop and increase employment and supported employment

opportunities, increasing the number of people with learning

disabilities who are in paid (full or part time) employment, or

voluntary roles. The Council wishes to see services that cater for both

the younger learning disability population with more complex needs that

are transitioning and ageing cohort of people with learning

disabilities. Wandsworth Market Position Statement

A learning disability is a reduced intellectual ability and

difficulty with everyday activities such as household tasks, socialising

or managing money. The NHS defines a learning disability as “the way a

person learns new things throughout their lifetime, which means they can

have difficulty understanding new or complex information, learning new

skills and coping independently”. The severity of learning disabilities

exists on a spectrum from mild to profound. At its greatest severity, a

profound learning disability leaves a person with multiple disabilities,

including learning, sensory and physical impairment .

Although the two terms are occasionally used interchangeably, a

learning difficulty differs from a learning disability. A learning

disability is a condition that affects all aspects of life where “a

learning difficulty is an obstacle to a specific form of learning but

does not affect other aspects of life”.

Learning disabilities are now taking a more prominent position within

both national and local agendas. The Care Act 2014 requires Local

Authorities to meet a person’s needs holistically. This encompasses an

acknowledgement of the wider determinants of wellbeing, such as

employment or socialisation. The Care Act legislation is strengthened by

the Mental Capacity Act 2005 which protects the right of individuals

and their families to make their own decisions.

All people should have the opportunity to be active citizens, live a

meaningful life, and make contributions to the community.

To ensure that Wandsworth Council is providing the best outcomes to

residents, a Learning Disability Clinical Reference Group ensures that

services are the needs of local people. Importantly, the Group includes

representation of people with a learning disability and their families.

Service implementation is guided by key principles of the Wandsworth

Learning Disability Commissioning Strategy 2021-26 that focusses on:

- My Voice is Heard – Coproduction

- Where I Live – Housing and Care Support

- What I Do – Employment and Day Opportunities

- Becoming an Adult – Transition

- I am Fit and Healthy – Improving Health Services

- I have Choice and Control in my Life.

A learning disability occurs when the brain is still developing

(before, during or soon after birth) and there are several causal

factors including:

- genetic factors

- illness or accident while the mother is pregnant

- lack of oxygen or trauma during birth

- premature births

- early childhood illnesses, accidents or seizures.

Diagnosis of learning disabilities generally occurs in childhood.

Mild learning disabilities are mostly commonly diagnosed during school

age when issues with reading, writing and numeracy are highlighted.

Other issues with socialising may also present. These are often known as

‘hidden’ learning disabilities.

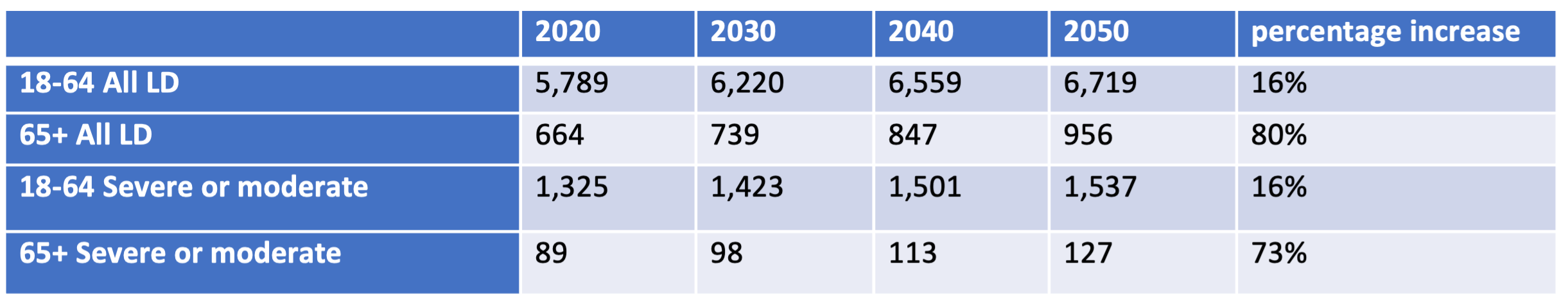

3.2 Prevalence and Level of Need

While the analysis in this section is pre-COVID, it is undeniable

that COVID-19 is going to have an impact on the needs of people with

learning disabilities in Wandsworth. National evidence shows that 30% of

the deaths of people with a learning disability between March and

September 2020 were from COVID-19. When the full impact of the pandemic

is known, including the potential long-term impacts of the virus, the

analysis will be revisited.

National prevalence rates applied to the age-related population in

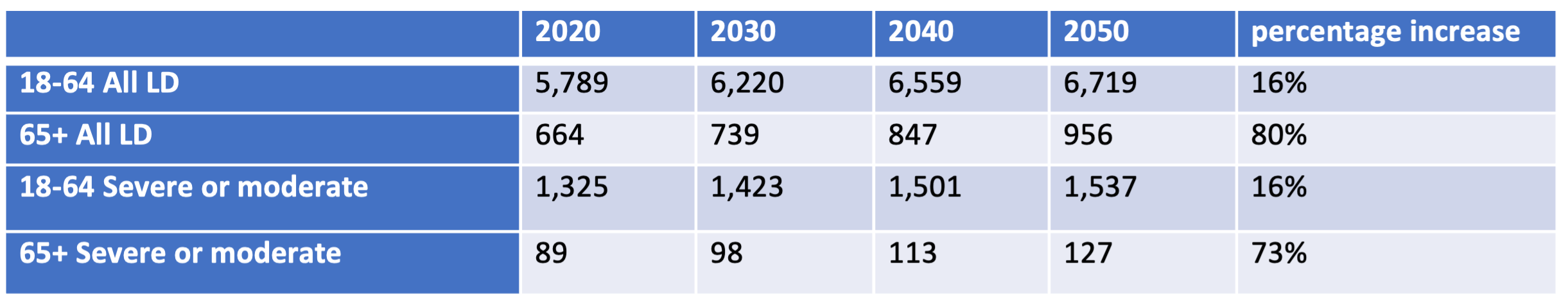

Wandsworth show a predicted increase of 16% in the numbers of the 18-64

population by 2050. However, the increase in the 65+ population is

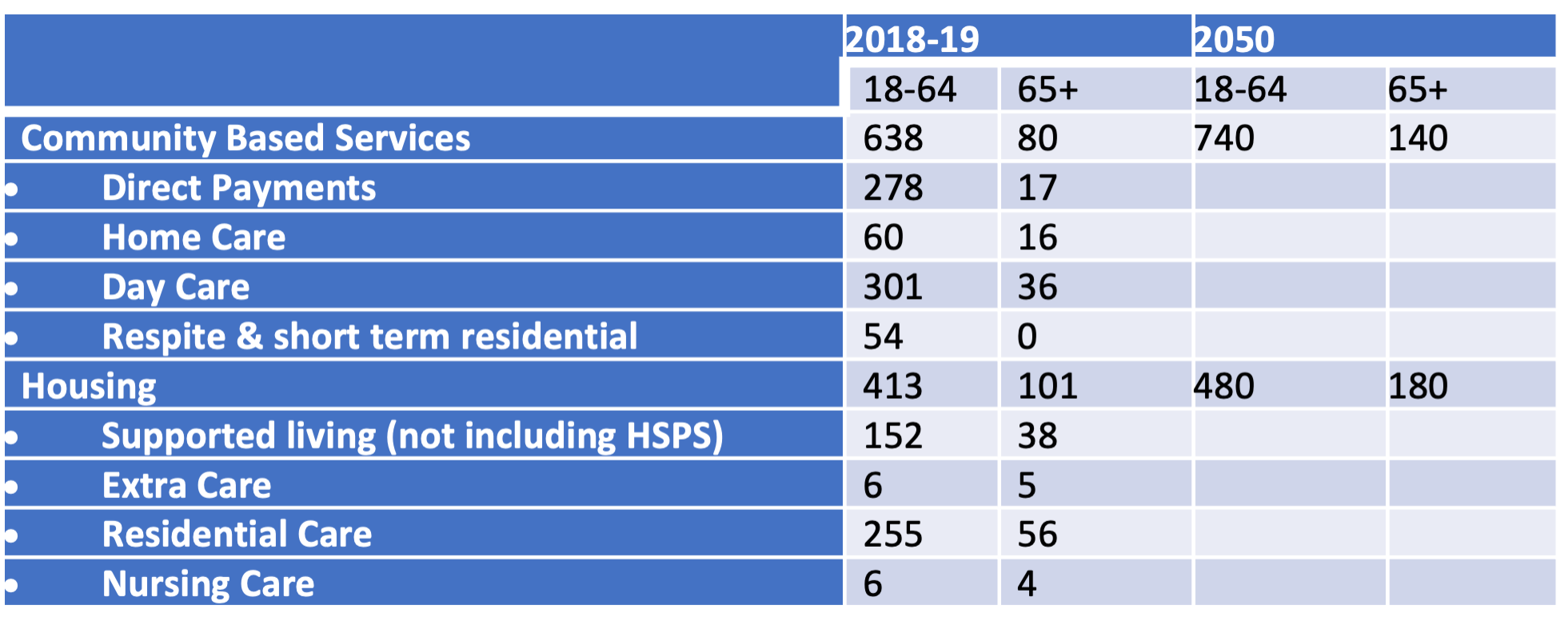

expected to be significantly higher, the table below.

Projections of Wandsworth residents with a

learning disability 2020-2050

Source: GLA population estimates & Emerson & Hatton, 2008

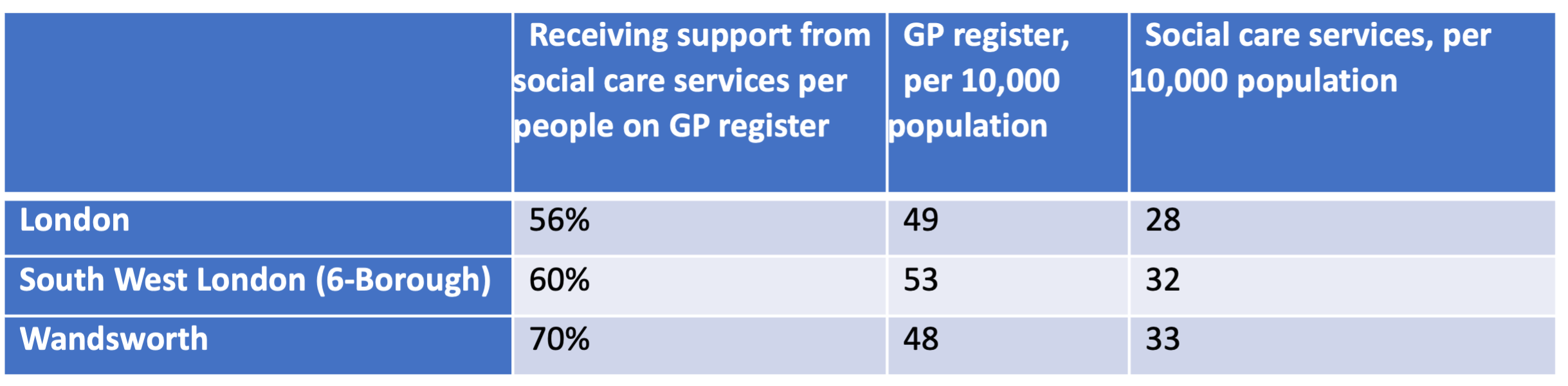

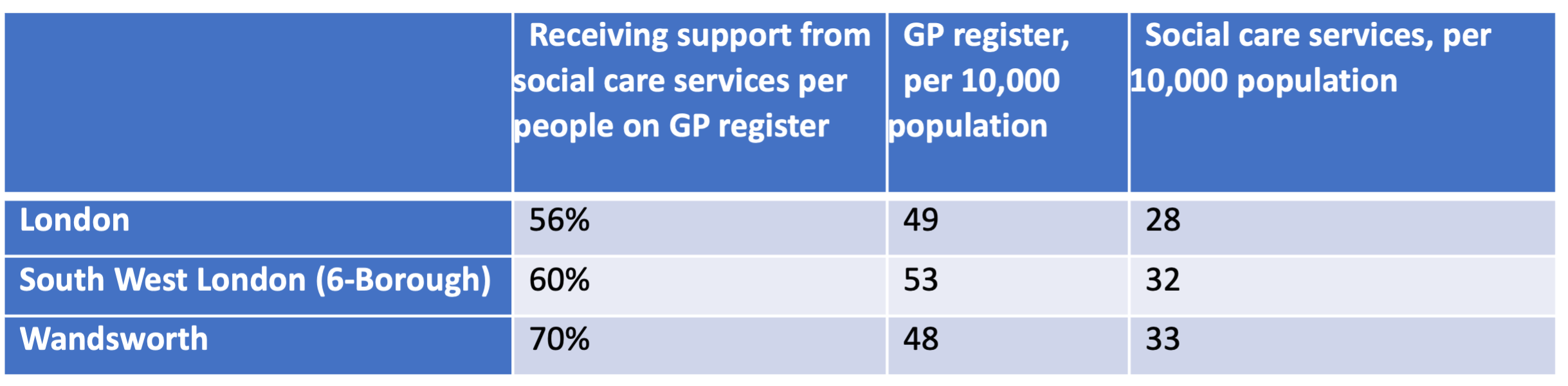

Comparing the number of people on the GP Learning Disability Register

shows a similar figure to the London average. 49 in every 10,000 people

in London are on the GP Register of people with a learning disability,

the number in Wandsworth is approximately 48 people. Similarly, the

number of people receiving social care services with the primary need of

learning disabilities is 33 compared to 32 South West London, as shown

in the table below.

Key statistics on learning disabilities in

Wandsworth

Source: Public Health Profiles

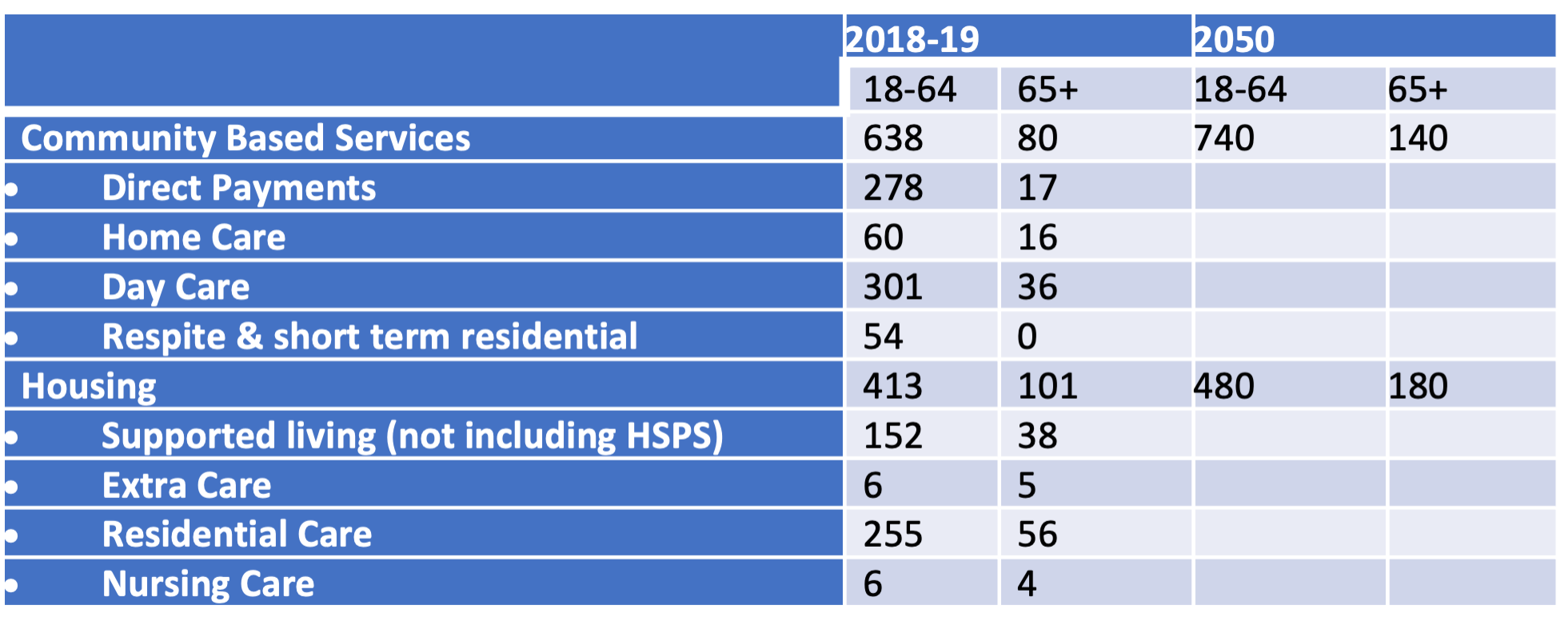

In 2018-19, there were 829 people aged 18 to 64 years with a learning

disability receiving services, and a further 131 people aged 65 and

over, as shown in the table below. Direct payments were one of the most

common ways to support people with a learning disability in the

community, given the emphasis on choice and control.

People receiving social care services for a

learning disability

Source: internal figures

The estimated increases to 2050 are based on the estimated population

rises of severe and moderate learning disabilities. The number of people

in nursing care look low. This is because these figures are based on the

primary care need of the person, not on all people with a learning

disability. As a person with a learning disability ages, their primary

need may become physical health or dementia.

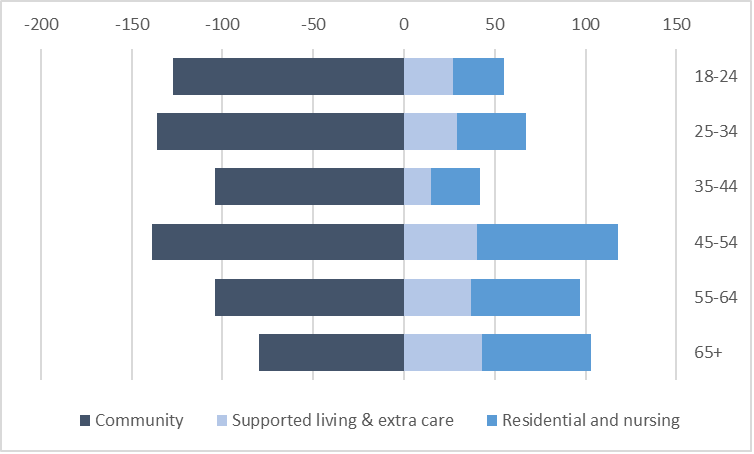

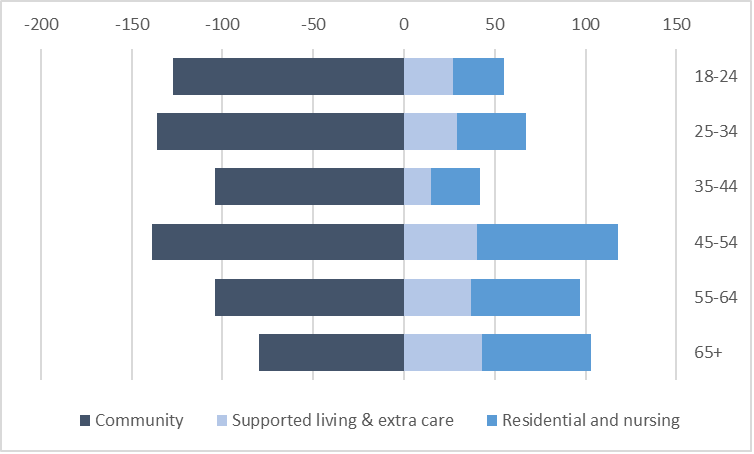

The figure below shows the number of people with a learning

disability receiving community based care (left hand side) and

accommodation-based care (right hand side) care by age in Wandsworth.

People with a learning disability aged 45+ are more likely to be placed

in accommodation-based support. More independent accommodation-based

care arrangements (supported living and extra care) make up more than

half the accommodation-based care placements from 18 to 44. From 45

years, people with a learning disability are increasingly likely to be

placed in residential care homes.

People receiving services for a learning

disability

Source: Richmond ad Wandsworth Council SSA Adult Social Services

Commissioning Division

Life Expectancy

The number of people living with a learning disability is expected to

increase in line with increases in the general population. Demand in all

areas is expected to rise. On average, females with a learning

disability live for 18 years less than the general population, males

with a learning disability for 14 years less. This is for a variety of

reasons including certain health conditions that have been found to be

more prevalent amongst people with a learning disability. For example,

epilepsy is 25.2 times and severe mental health conditions is 8.4 times

more prevalent than people without a learning disability :

- About 1 in 3 people with a mild to moderate learning disability also

have epilepsy. The more severe the learning disability, the more likely

the person will also have epilepsy

- People with Down’s syndrome will typically have some level of

learning disability, the extent of the learning disability will vary

individually

- As many as half of the people with cerebral palsy also have a

learning disability

- Studies vary in the overlap between autism and learning disability

but most show between 44% and 52% of autistic people may also have a

learning disability, and between 31% and 36% of people with a learning

disability may also be autistic

- People with a learning disability (particularly those with Down’s

syndrome) are at increased risk of developing dementia

- Older people with a learning disability experience age-related

issues at a younger age than the general population.

Primary Care

A national survey of 47% of people with a learning disability,

registered with a GP, showed there is lower attendance of health checks.

For example, only 31% of women have had smear tests compared to 73.2% of

the general population. A person with a learning disability may also

require higher levels of explanation regarding a diagnosis or health

deterioration, including an easy read format and the involvement of

advocates. Research found that 38% of people with a learning disability

died from an avoidable cause, compared to 9% in a comparable population

.

In Wandsworth, 53% of adults with a learning disability on GP

Registers had a health check during 2017-18. This is similar to the

England’s average (52%) but slightly lower than the London average

(57%).

Social Isolation

Evidence reveals that high-quality friendships are associated with

better physical health and lower risk of early mortality. A lack of

social interactions can increase the likelihood of high blood pressure,

heart disease, obesity, weakened immune system, anxiety, depression and

cognitive decline. A recent survey stated that 45% of people with a

learning disability felt they did not spend enough time with friends,

with 18% feeling alone and cut off from other people .

People with a learning disability may have limited opportunities for

inclusion to a variety of social groups and may be limited by

availability of services or carer preferences.

In some communities there are low levels of awareness and

understanding from the general public who may not involve and value

people with a learning disability.

Many people with a learning disability aspire to having a loving

relationship. However, only 3% of people with a learning disability live

as a couple compared to 70% of the general adult population. Support

workers and family members can play an influential role in either

supporting or preventing people developing and sustaining these

relationships

Meaningful Activity, Employment, Training and Education

Less than two in ten people with a learning disability are in

employment, which decreases further for those living with a severe

learning disability. In Wandsworth, the latest statistics show 11% of

people with a learning disability (known to services) are in paid

employment compared to the London average of 7.5% and England average of

6.0%. The gap in employment rates in Wandsworth is similar to the London

(66%) and England (70%) averages .

Meaningful activity needs to be tailored to the individual needs of

the person. The assumption that all people with a learning disability

need the same service runs counter to the strengths-based approach to

social care, and the personalisation agenda. Activities need to fit the

interests of the person as well as being age appropriate. Wandsworth has

a firm commitment to achieving equality for those with a learning

disability and the wider population. Evidence shows people with a

learning disability feel they do not get the social contact they need,

and meaningful activity levels can be low .

Meaningful activity must be tailored to the individual needs.

Wandsworth is committed to expanding a strength-based approach,

commissioning services and support which are appropriate for

everyone.

Research demonstrated 38% of people with a learning disability died

from an avoidable cause versus 9% in a comparable population. Easy

access to health care is key to helping people with disabilities live

long and healthy lives .

Housing

Two thirds of people with a learning disability remain living with

their families. As the family ages, this situation may become

unsustainable. If long term support plans are not in place for the

person with learning disability may result in multiple moves and

placement in inappropriate accommodation .

In Wandsworth, 73% of people with a known learning disability are in

settled accommodation, similar to the London average (73%), lower than

the England average (77%). An alternative measure of people with a

learning disability in stable and appropriate accommodation showed 74%

in Wandsworth, similar to the London average of (75%).

Transition

Young people with a learning disability transitioning into adulthood

face a variety of challenges. These include : • some young people

receiving SEND support in childhood may not be eligible for adult social

care support because the criteria is set at a higher level. This is an

area of potential unmet need as this group are vulnerable to

exploitation and anti-social behaviour • different legislative

frameworks relating to under 18 (children) and over 18 (adults) mean

different expectations of available support • contributions towards the

cost of adult support is dependent on the income of the person with

learning disabilities • young people with a profound or multiple

learning disabilities may find it difficult to comprehend the changes

that are occurring with their life and support packages • as a young

person with a learning disability grows up, they may find that they want

to live more independently • moving out of the family home can cause

more challenges and the young person may need specialised support,

either accommodation-based or community-based.

The change into adulthood (and adult based services) can be deeply

stressful for many young people with a learning disability and

transition is, therefore, a key area of priority within Wandsworth. The

0–25 team in Wandsworth’s Children’s Services was set up to address

these changing needs.

3.4 Current Services on Offer

Partnerships with the NHS and the vibrant voluntary sector add to the

variety of services that support the wellbeing of people with a learning

disability in Wandsworth. The Community Learning Disability Health Team

(CLDHT) run by South West London and St George’s Mental Health Trust

provide a specialist pathway to people with learning disability needs

who may have difficulty accessing mainstream services. Specialist

services include support of dieticians, dysphagia practitioners and

speech and language therapists. One Trust is a registered charity that

promotes the wellbeing of people with learning disabilities through day

centre support. The organisation aims to ‘maximise the potential’ of all

people by tailoring support specifically to the person and their

families. In Wandsworth there are services available to ensure the

specific health needs associated with learning disabilities are met.

Partnerships with the voluntary sector also ensure that people with a

learning disability receive holistic services that enable them to lead

fulfilled lives.

There are several out-of-borough residential care placements for

Wandsworth residents. Moving a person with a learning disability

regularly can be disruptive for the individual, family and social

networks. The priorities are for new placements is to keep people

in-borough, and to bring people back in-borough when possible.

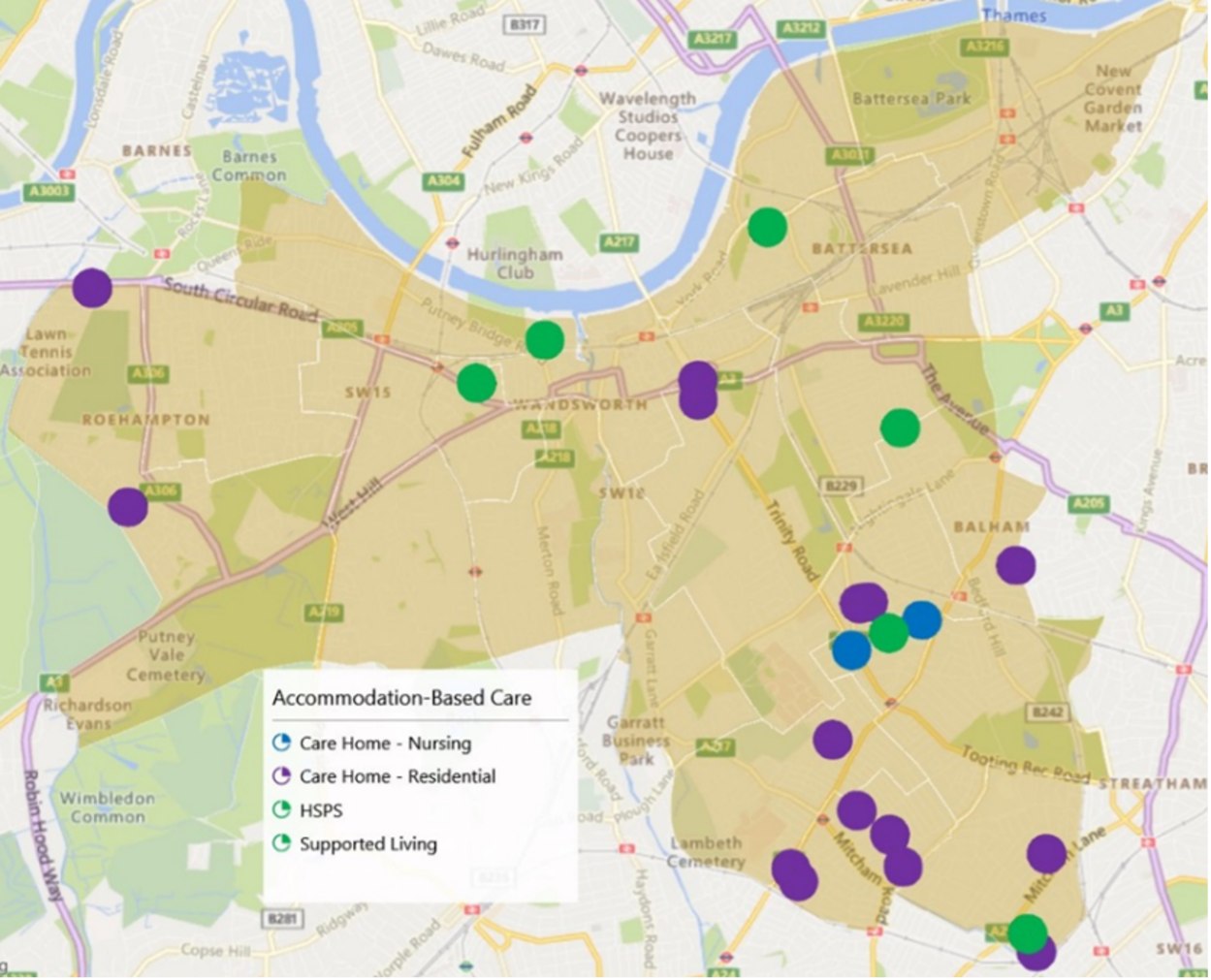

There are 12 residential care homes in Wandsworth designed

specifically for people with a learning disability, and another two

general needs care homes.

There is one Supported Living and four Housing Support and

Preventative Services (HSPS) schemes (some consisting of multiple homes)

for people with a learning disability. In addition, some HSPS Support is

given as floating support in locations around the Borough.

In Wandsworth HSPS operates as a Block Contract Service in addition

to the supported living provisions which are spot purchased. HSPS is a

local term which refers to services that would formerly have been

commissioned under the Supporting People Programme. Whilst both HSPS and

Supported Living provide a range of support to tenants, there are key

differences:

- HSPS is not regulated by the Care Quality Commission (CQC).

- Supported Living is not necessarily regulated by CQC, but elements

of personal care may be subject to personal care

- HSPS provides housing related support services only and does not

include personal care or domestic support

Although the number of units varies over time, there are currently

approximately 20 units (the figure below).

Map of accommodation-based support for Learning

disabilities in Wandsworth

Source: Richmond ad Wandsworth Council SSA Adult Social Services

Commissioning Division

Transition

The transfer to adult services can be deeply stressful for many young

people with a learning disability. Wandsworth regards this as a priority

for support and, where young people are not eligible for adult social

care services.

Settled Accommodation

Two thirds of people with a learning disability remain living with

their families. As the family ages, this situation may become

unsustainable. In Wandsworth, the number of people with a learning

disability in settled accommodation is lower than the London and England

averages. While these figures may be skewed by the lack of

identification of people with a mild learning disability, an area which

needs further exploration.

There is a high proportion of older people with learning disabilities

who receive support in care homes. Further analysis should be undertaken

to explore if older people with a learning disability have services

which enable them to remain living independently at home if they

wish.

A high proportion of people with a profound learning disability are

cared for in out-of-borough placements, highlighting the lack of

appropriate support locally. Moving people with a learning disability

away from familiarity and their families can cause emotional stress for

everyone.

The dynamics of learning disabilities in Wandsworth is varied with an

increasing proportion of learning disability needs in older people. A

variety of services are available to support those with greater need in

the community or in accommodation. The voluntary sector services

advocates and promotes rights and independence through holistic

approaches.

The prevalence of learning disabilities in older people is set to

increase significantly by 2050 . Services must develop so learning

disability needs continue to be met holistically, including social and

economic aspects. Wandsworth needs to ensure services for older people

include provision for people with a learning disability. Many people

with a learning disability may receive accommodation-based support for a

primary need other than learning disabilities.

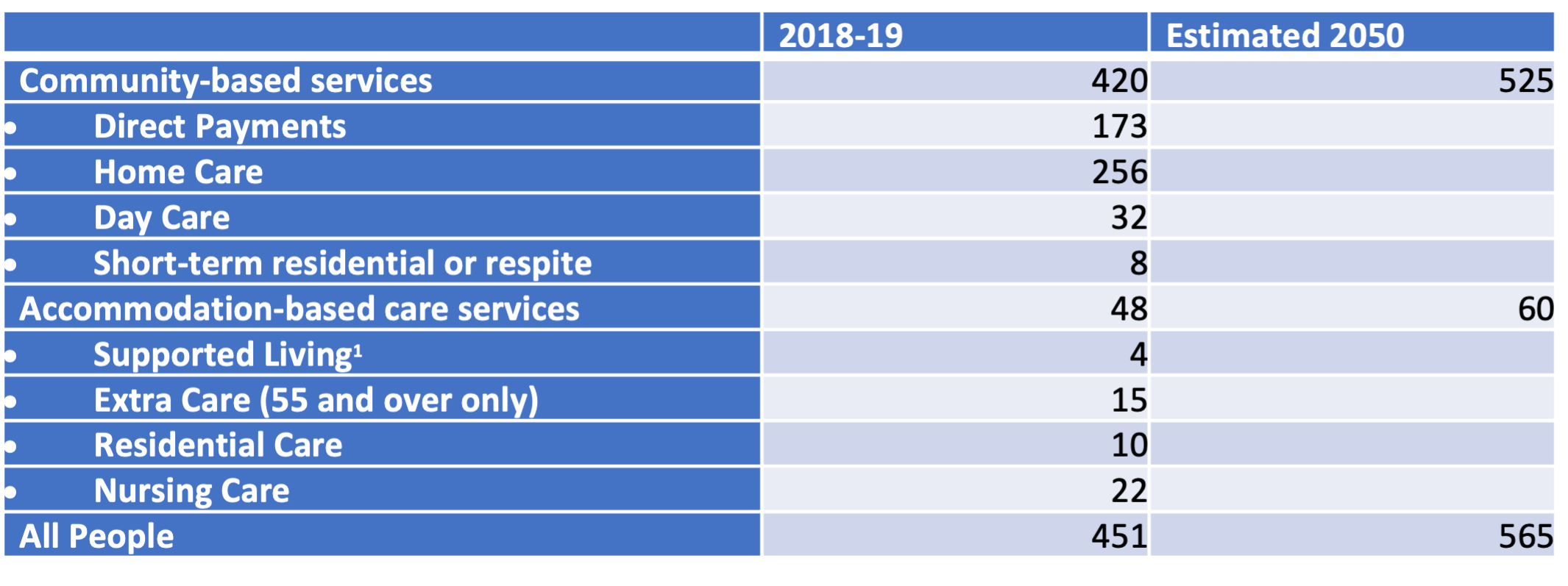

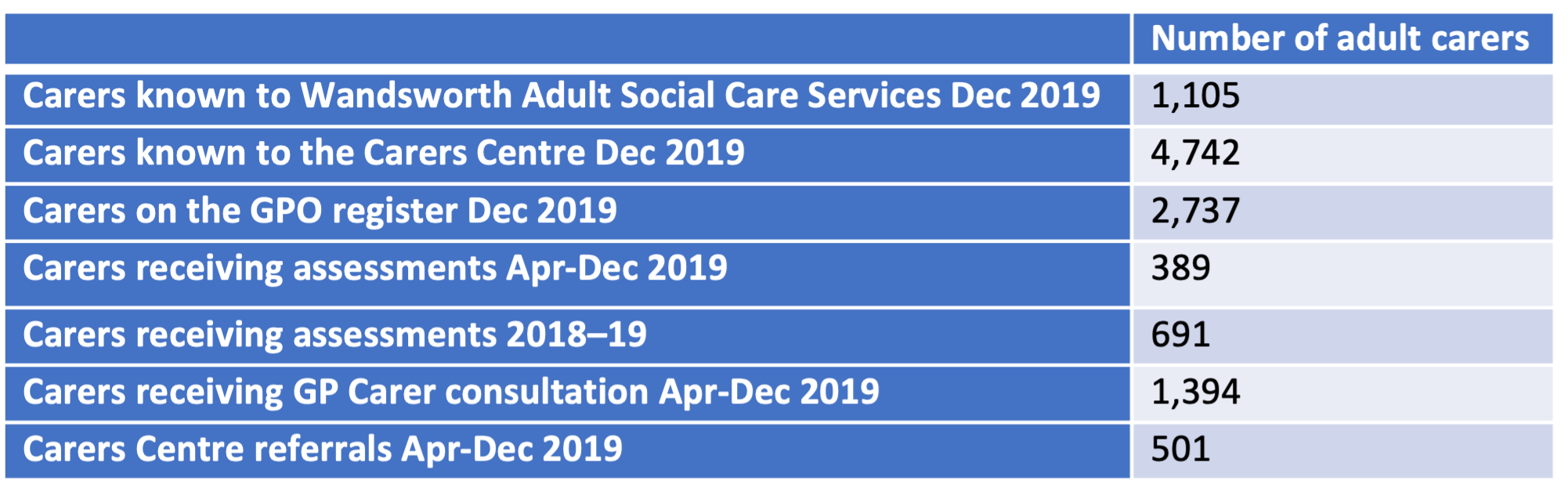

4. Unpaid Carers

A detailed needs assessment was carried out in 2019 and is available

on DataWand. This

section summarizes the key points and updates some of the figures.

4.1 Introduction

“Our vision in Wandsworth is to raise awareness of the vital roles

played by carers and young carers; to collectively provide good quality

personalised support to carers, and young carers and those they care

for; to build solid networks ensuring that carers and young carers know

where to go for information and support; to enable carers and young

carers to balance their own lives with their caring roles, and; to

ensure that local service providers understand these needs and are

committed to working together to meet them.” Wandsworth Market Position

Statement

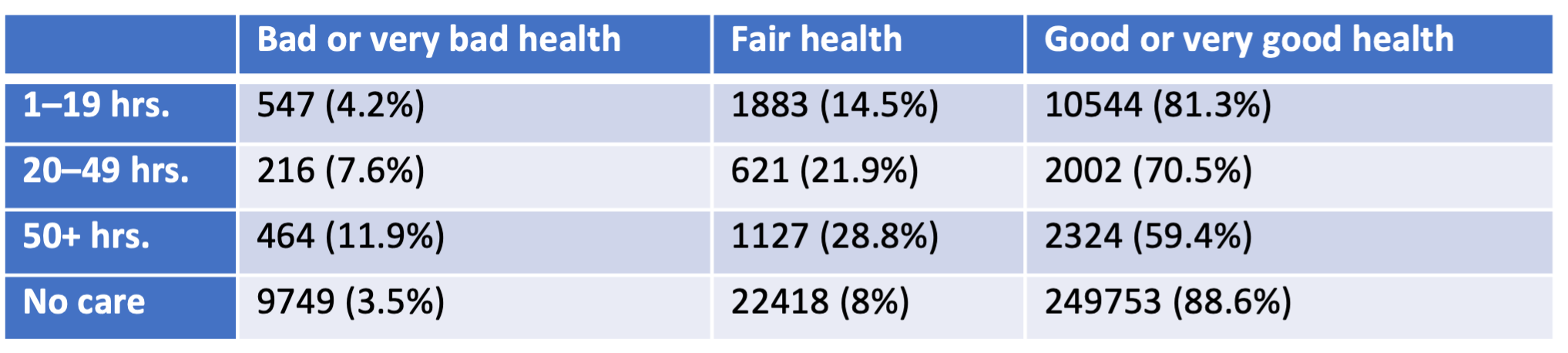

Unpaid carers provide invaluable support to the people they look

after, and to health and social care services. However, the life of a

carer can be hugely challenging. Carers may be at risk of social

isolation, losing employment and education opportunities, as well as

caring having a detrimental impact on physical and mental well-being.

Carers must remain a high priority for central and local governments to

ensure they feel they have choices, respect, and value.

A carer is anyone who provides care to a friend or family member who,

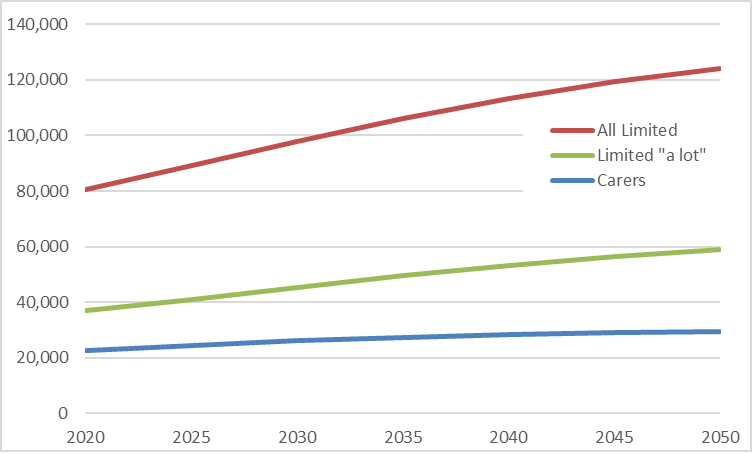

because of a limiting long-term condition or addiction, is unable to

cope independently. Nationally, it is estimated that the number of

carers will increase by 60% to 3.4 million people by 2030 .

Wandsworth estimates are shown in section 4.3.

The Care Act 2014 and the Children’s and Families Act 2014 recognises

the importance of carers and aims to promote their physical and mental

well-being. All carers (including young carers and adult carers of

children) have a right to a carer’s assessment and relevant support .

The 2010 National Carers Strategy aimed that by 2018 every carer

should be:

- recognised and supported as an Expert Care Partner

- enjoying a life outside caring

- not financially disadvantaged

- mentally and physically well and treated with dignity

- children will be thriving, protected from inappropriate caring

roles.

The National Carers Action Plan 2018–20 outlines a range of

cross-cutting governmental actions based on five key themes:

- services and systems that work for carers

- employment and financial well-being

- support for young carers

- recognition and support for carers in the wider community and

society

- building research and evidence to improve outcomes for carers.

The social, financial and health impacts upon carers can be

considerable. People providing unpaid care may be unable to protect

their current and future financial security .

Most of the care is provided by family, friends, and relatives. The

care they provide is worth an estimated £132bn per year . Notably this is

more than total spending on the NHS, which was 124.7 billion in 2017/18

.

This equates to an average of £20,300 contribution from each unpaid

carer in the UK. If this average was applied to the Wandsworth Carers,

it is estimated that they provide over £450 million of care.

Despite the significant contribution carers are making to society and

the health and social care system, the 2017 State of Caring Survey found

that 73% of carers felt that their contribution was not valued or

understood by government. Therefore, it’s vital that carers are given

the recognition and support they need to continue to provide care.

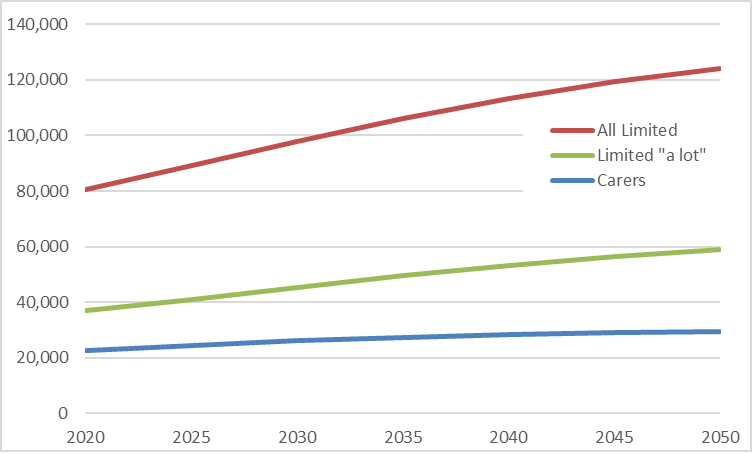

As people are living longer with health and social care needs, the

gap between the number of carers and the number of people with limiting

long-term conditions is increasing. This means:

- an increasing number of people will become unpaid carers with all

the increasing attendant needs

- an increasing need for social care support for people without an

unpaid carer.

The number of “sandwich carers” (those looking after young children

at the same time as caring for the older generation) is expected to rise

as are the number of people with ageing parents increases.

4.2 Identification of the Caring Role

The number of carers in the 2011 Census compared to the

number of carers known to services, indicates there is a gap in

identification. Carers often do not recognise their role and only

associate with their primary relationship to the person. Most of us will

look after an elderly relative, sick partner, or disabled family member

at some point in our lives. This invaluable service undoubtedly ensures

the continued health, well-being, and comfort of many cared for people.

One of the reasons people require social care services is due to unpaid

carers becoming unable to continue. Failure to identify carers and offer

support at an early stage represents a potential future risk.

Data show three in five people will be a carer at some point in their

lives. Women are more likely to be carers, often with multiple caring

responsibilities such as for children and elderly relatives. Older

people often become carers for their partner .

The UK 2011 census showed the proportion of the

population who were carers had increased and evidence and this trend is

likely to continue. The number of people aged 65+ is increasing more

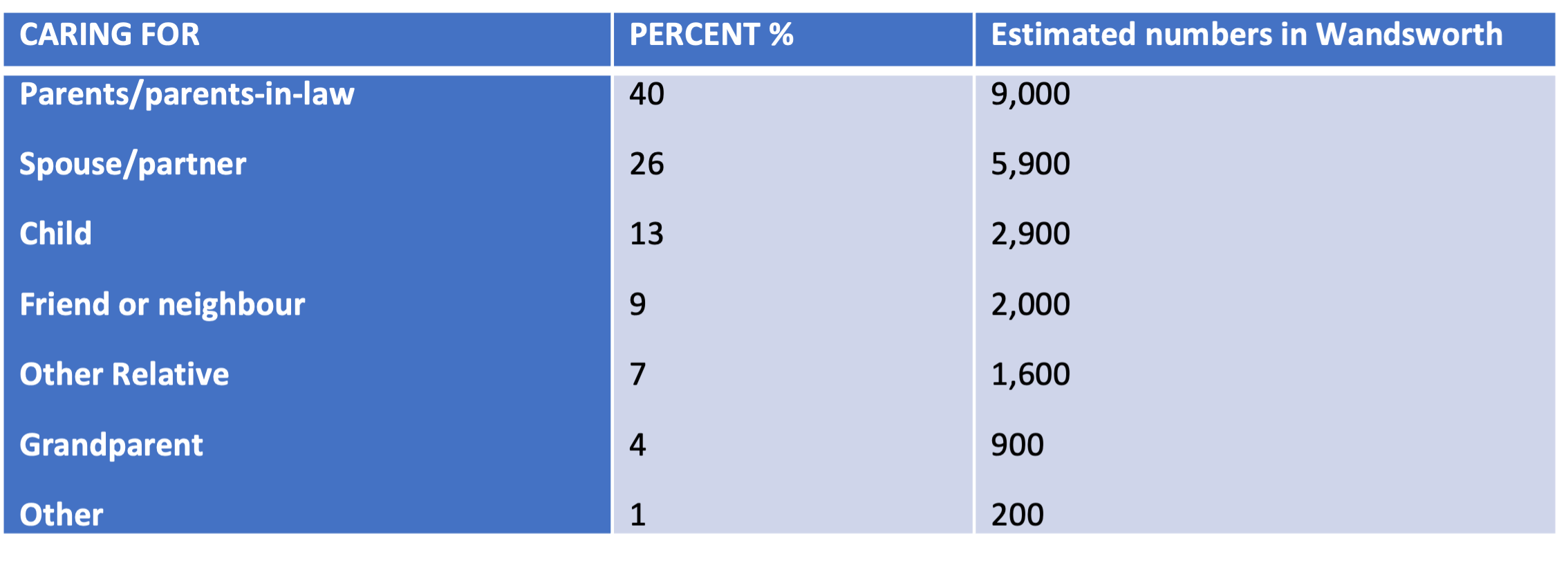

rapidly than the general population.

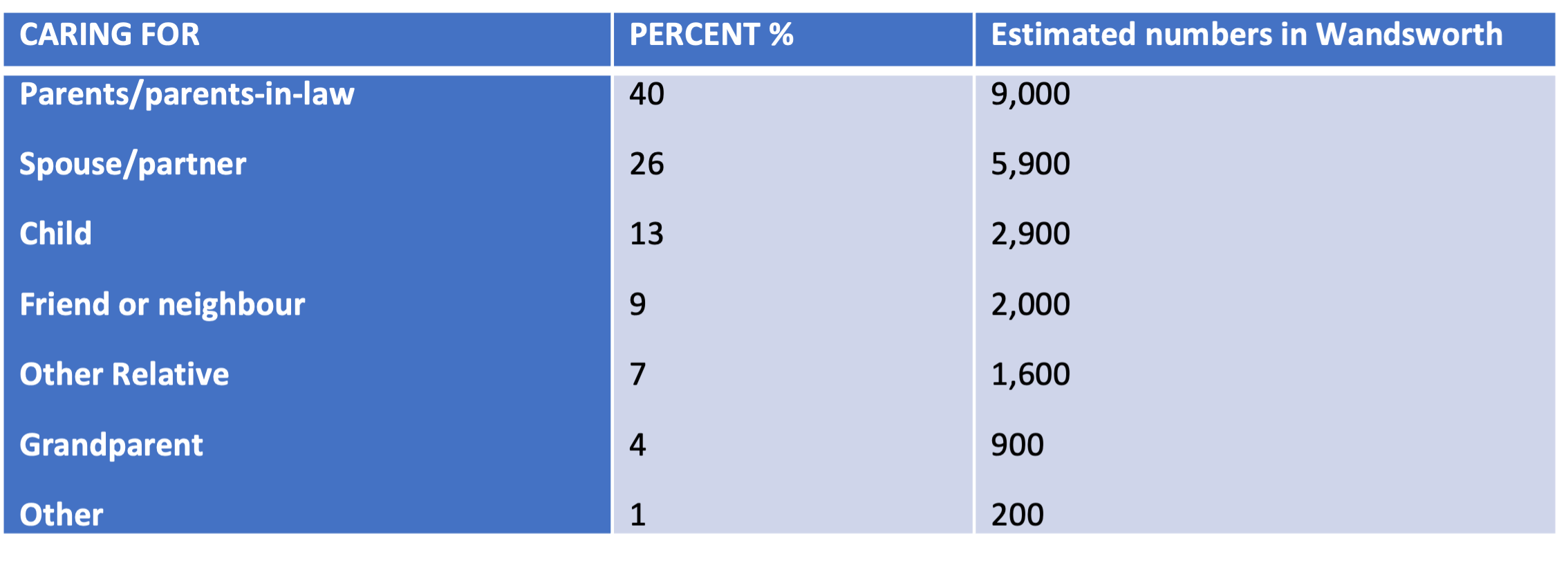

83% of carers care for one person. However, 14% care for two people,

and 3% are caring for three or more people. The largest group receiving

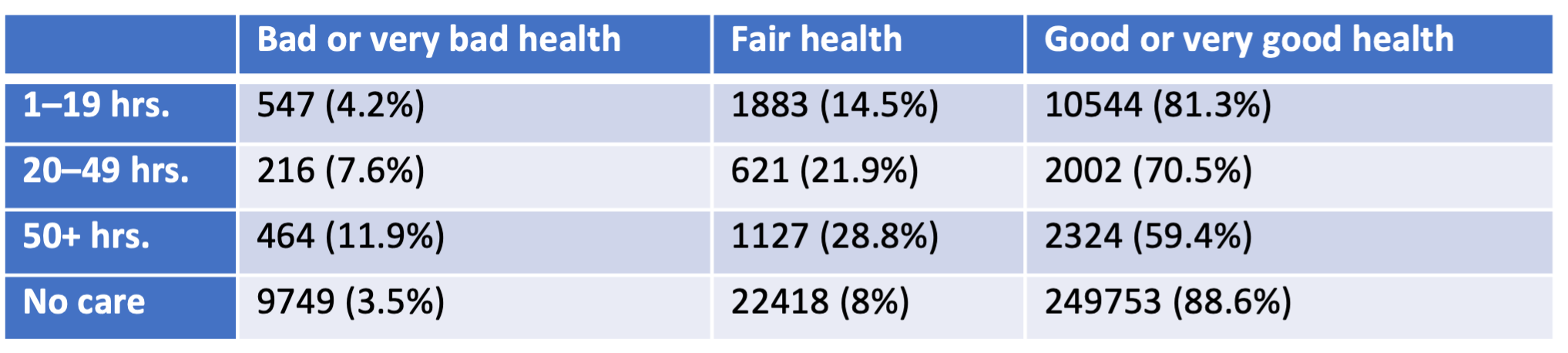

care is parents and parents-in-law (the table below). Carers of older

people make up approximately three-quarters of all carers. Middle-aged

carers may have dependent children whilst also caring for older

parents.

Cared for person by percentage of UK

carers

Source: ONS: Census 2011

Young Carers

The 2011 Census identified there are 1,719 young carers under 25

years providing unpaid family care in Wandsworth. Assuming the same

proportion applied to the 2020 population, an estimate 1,890 children

and young adults are providing care.

All young carers identified by the Council are offered assessment and

appropriate support through the Wandsworth Children’s services.

Many young carers take on their role because of multiple care needs

in the family. Growing up in such an environment, young carers mature

quickly and gain practical skills that aid independence. However,

national research shows that caring can have an adverse impact on

educational attendance, attainment, physical and emotional health,

social activities, and individual aspirations. Young adult carers’

responsibilities may delay them for moving away from home, reducing

employment possibilities, and accessing further education .

Transition arrangements are crucial for improving employment and

higher education opportunities. Carers aged between 16 and 18 years are

twice as likely not to be in education, employment, or training. Of

those who are in education, 56% at college or university said they were

struggling with their studies. 30% said they may have to drop out (17%

because of their caring role and 13% for financial reasons). Young

carers are three times more likely than their peers to have a mental

health condition .

55% of young carers provide care to a parent whilst 25% care for a

sibling. 80% of young carers are helping with practical tasks such as

cooking and household chores. Responsibilities tend to increase with age

.

Young carers risk being hidden and not receiving appropriate support

because :

- they do not realise they are a carer or that their life is different

to their peers

- their parents do not recognise their children are carers

- they do not want to be different from their peers

- one in four young carers were bullied specifically because of their

caring role

- they worry the family will be split up and they, or their siblings,

may be taken into care

- their parent’s condition may not be obvious, so people do not

realise they need help

- no opportunity to share their story

- lack of understanding of available sources of support.

Even when young carers are known to services, some will under state

their caring role and the affect it has on them. In the 2011 census, 442

children aged 0–15 years and 1,348 young people aged 16–24 years,

provide unpaid care in Wandsworth. The experiences of LGBT+ young adult

carers can be even more challenging. Research by the Carers Trust

indicates that LGBT+ young adult carers are three times more likely to

experience bullying than young adult carers. They are three times more

likely to have a mental health problem than their peers .

Parent Carers and Sandwich Carers

Applying national research to Wandsworth’s population it is estimated

there are 2,900 parent carers, approximately 13% of the carer

population. Some of these will be caring for “adult children”. However,

there are 5,800 school pupils who have Special Educational Needs and

Disabilities (SEND). Most of these children will be cared for by their

parents but some may not. This suggests a discrepancy between the number

of parent carers identified, and the total number of parent carers .

Sandwich carers are those who combine care for an older relative with