JSNA Age Well

1. Introduction

The population is ageing with the large cohort of people now reaching their later years. This increased demand is only set to continue as the population is living longer. By tackling wellbeing earlier in the life course, the outcomes for older people can be significantly improved and the most vulnerable people in society will continue to have access to high quality services. Important resources that have been used to compile the JSNA include use of the following, alongside additional background information, data, and intelligence:

- Office for Health Improvement & Disparities (OHID)

- Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF)

- Projecting Adult Needs and Service Information (PANSI)

- Projecting Older People Population Information (POPPI)

- NHS Digital

- Office for National Statistics

- NHS England Statistics

- Wandsworth Health and Care Plan

- eSouth West London STP. Care Home Data Pack 2019

- Wandsworth Dementia HNA 2019

- DataWand.

1.1 Demographics

For latest demographic information please go to the population explorer on DataWand.

Population

65+ Population Pyramid

In Wandsworth in 2024, 9.9% (n=33,154) of the total population were 65 years old and over. The proportion of people aged 65+ in the borough is 19.6% lower than the London average of 12.3%.

In line with the national picture, the number of older people in Wandsworth is increasing, many of whom will live with age-related needs that will make them more vulnerable to experiencing difficulties with mobility and personal care. The population of residents aged 65+ is projected to increase between 2023 and 2041 by 58.7% (from 32,468 in 2023 to 51,617 in 2041).

Source: © GLA 2021-based demographic projections. Housing-led population projections. Past Delivery 10-year migration, 2023

Ethnicity Breakdown of Population Aged 65+

In Wandsworth in 2024, 28.2% (n=9,772) of the total population aged under 18 were from BAME ethnic groups. The proportion of residents aged 65+ from BAME ethnic groups in the borough is 9.7% lower than the London average of 31.3%.

Source: © GLA 2016-based Demographic Projections, 2017

1.2 Life Expectancy at Age 65

Life expectancy at age 65 is an estimate of the average number of years at age 65 a person would survive if he or she experienced the age-specific mortality rates for that area and time period throughout his or her life after that age. Healthy life expectancy at age 65 shows the years a person can expect to live in good health beyond 65 years, rather than with a disability or in poor health.

Males

Life expectancy at 65: In 2020 - 22, Wandsworth’s rate was 18.3 years, which was the 15th highest in London, 0.4% lower than the England average and 0.1% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2020 - 22 was also 16.0% higher than in 2001 - 03, in comparison with 12.9% increase in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Females

Life expectancy at 65: In 2020 - 22, Wandsworth’s rate was 21.6 years, which was the 13th highest in London, 3.2% higher than the England average and 1.2% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2020 - 22 was also 13.6% higher than in 2001 - 03, in comparison with 8.7% increase in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

1.3 Healthy Life Expectancy at Age 65

Males

Healthy life expectancy at 65: In 2018 - 20, Wandsworth’s rate was 10.3 years, which was the 16th lowest in London, 1.6% lower than the England average and 0.3% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2018 - 20 was also 5.2% lower than in 2009 - 11, in comparison with 5.8% increase in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Females

Healthy life expectancy at 65: In 2018 - 20, Wandsworth’s rate was 14.3 years, which was the 2nd highest in London, 26.2% higher than the England average and 28.3% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2018 - 20 was also 2.1% higher than in 2009 - 11, in comparison with 6.6% increase in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

1.4 Inequalities in Life Expectancy at Age 65

Males

Inequality in life expectancy at 65: In 2018 - 20, Wandsworth’s rate was 3.7 years, which was the 9th lowest in London, 28.8% lower than the England average and 22.9% lower than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2018 - 20 was also 14.0% lower than in 2010 - 12, in comparison with 13.0% increase in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Females

Inequality in life expectancy at 65: In 2018 - 20, Wandsworth’s rate was 4.0 years, which was the 12th highest in London, 16.7% lower than the England average and 11.1% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2018 - 20 was also 11.1% higher than in 2010 - 12, in comparison with 20.0% increase in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

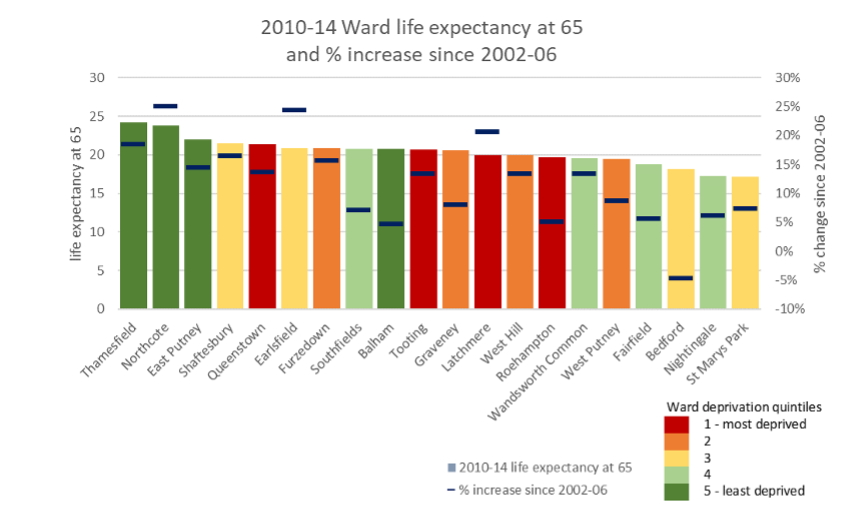

1.5 Ward-level Life Expectancy at Age 65

The latest (2010–14) Ward-level life expectancy at age 65 and percentage change in life expectancy since 2002–06 (the figure below) Life expectancy at age 65 was the highest in three wards in the least deprived quintile, the same Wards had the highest life expectancy at birth. The relationship between deprivation and life expectancy at age 65 in other deprivation quintiles is less clear, with the most deprived wards having either average or low life expectancy (LE) at age 65. There was a substantial variation in relative gains in life expectancy at age 65 at a Ward-level. Bedford was the only Ward with percentage decrease in life expectancy at age 65 between 2002–06 and 2010–14 (4.6% reduction in LE at age 65). The highest gains in life expectancy at age 65 of over 20% were recorded in Northcote, Earlsfield and Latchmere.

Source: London DataStore: Life Expectancy at Birth and Age 65 by Ward and London Wards Indices of Deprivation

2. Main Causes of Morbidity and Mortality

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 1 provides modelled estimates of the burden of poor health and disability. The burden of disease analysis is a way to compare the impact of different diseases, conditions or injuries in a population and break it down by age group. The only age group for older adults that is available in the GBD toolkits is 70 and over. The impact of disease on Wandsworth older adults can be divided into morbidity (living with a disease) and mortality (dying from a disease).

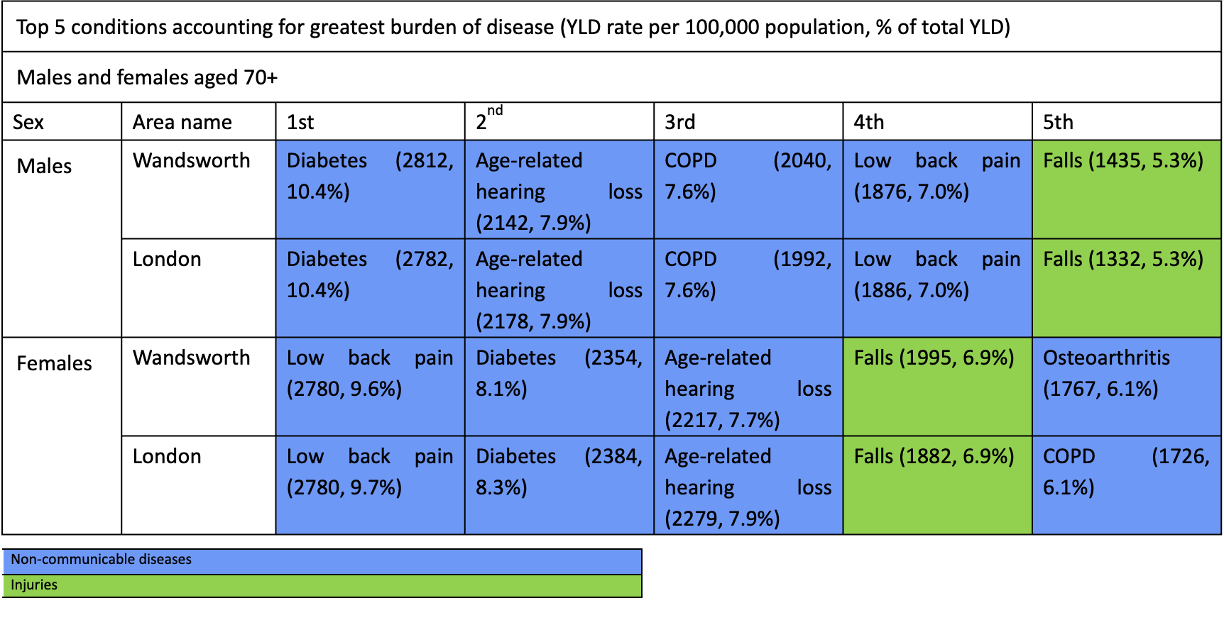

2.1 Morbidity in Older Adults

The GBD also provides modelled estimates of the burden that can be attributed to a number of risk factors. It uses years lived with disability (YLD) to attribute the burden of morbidity. YLD is a measure of morbidity that combines the prevalence of each disease with a rating of the severity of its symptoms (excluding death itself), to give an overall measure of the loss of quality of life.

Low back pain, age related hearing loss, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) , followed by lower back pain and falls were the most common causes of YLD in both Wandsworth and London males. For females, the top four causes are the same for Wandsworth and London: lower back pain, diabetes, hearing loss and falls. COPD was the 5th most frequent cause in London, whereas for Wandsworth’s females, it was Osteoarthritis (table below).

Source: Global Burden of Disease. 2019

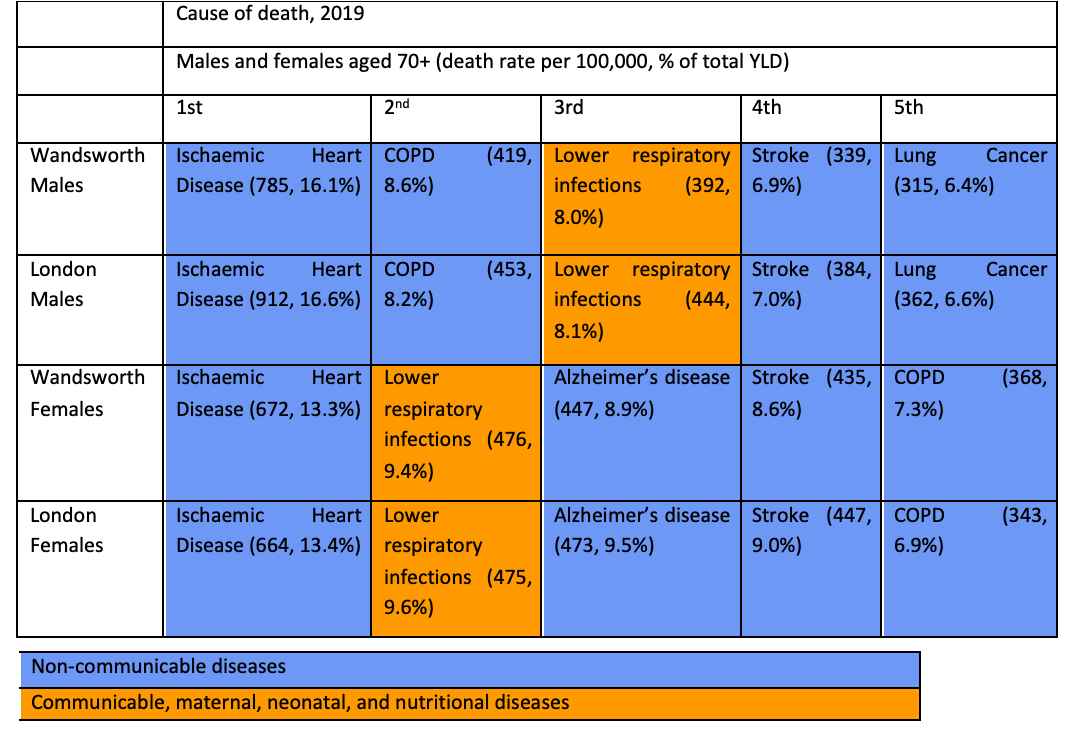

2.2 Mortality in Older Adults

In 2019, ischaemic heart disease was the leading cause of death in males aged over 70 years, followed by COPD and lower respiratory infections. Top 5 causes of death in London were the same; the main difference was in mortality rate from heart disease: Wandsworth’s rate was 14% lower than the London average rate (785 per 100,000 vs. 912 per 100,000 population).

In females aged over 70 years, ischaemic heart disease, lower respiratory infections and Alzheimer’s disease were the leading causes of death in Wandsworth and in London (table below).

Source: Global Burden of Disease. 2019

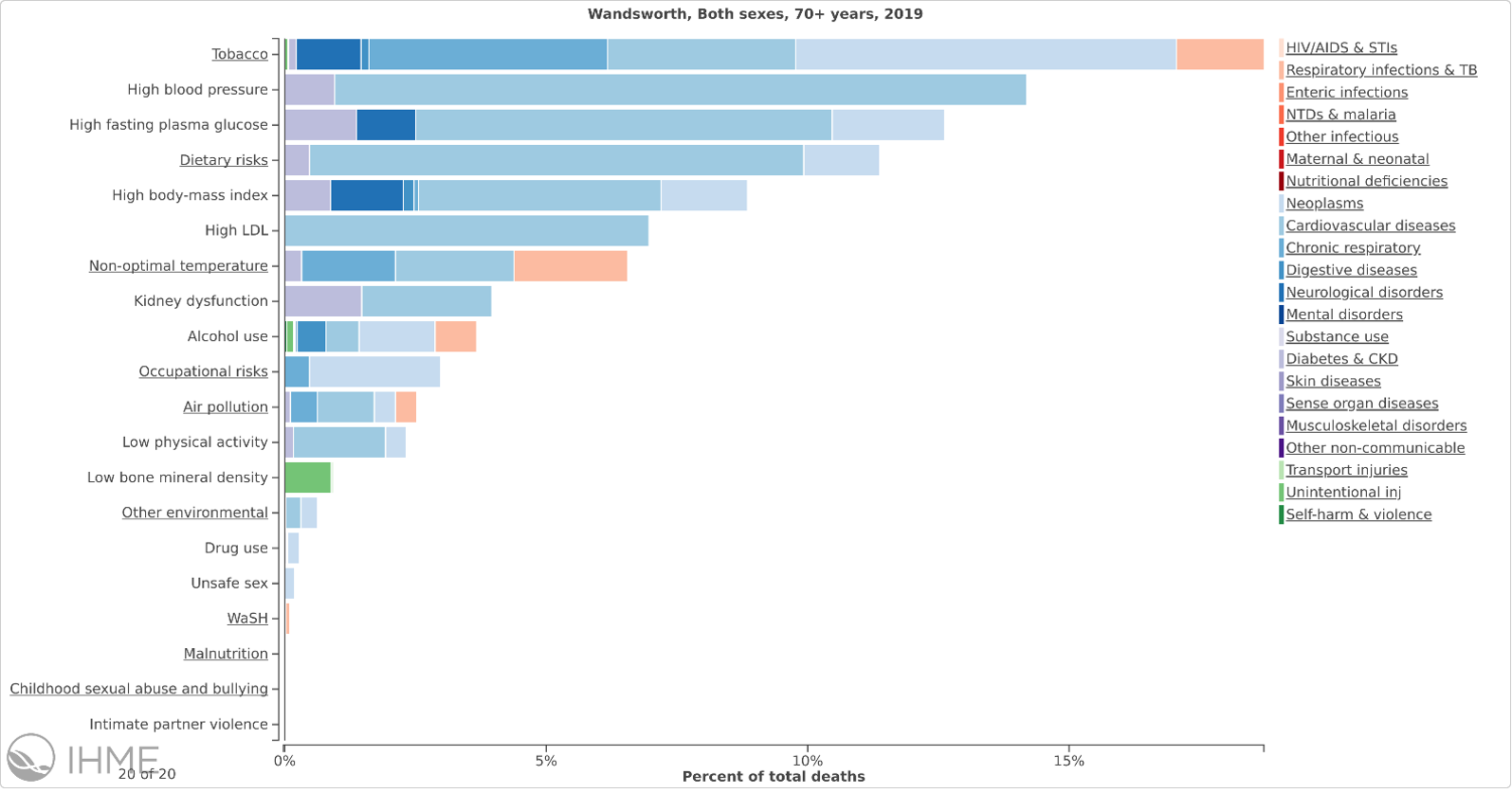

Mortality Risk Factors

Causes of death in the population are influenced by a broad range of factors. Using the Global Burden of Disease, certain risk factors for disease can be ranked based on the proportion of deaths they are associated with. Risk factors are divided into 3 main groups: behavioural, metabolic and environmental.

The risk factors accounting for the highest proportion of deaths among those aged over 70 years was tobacco, high blood pressure, high fasting plasma glucose and dietary risks. Smoking accounted for deaths from five major causes: neoplasms, chronic respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases and respiratory infections (figure below).

High blood pressure accounted for deaths from two main causes, cardiovascular diseases (heart disease and stroke) and diabetes and kidney diseases. High blood sugar level contributed to cardiovascular, cancer, diabetes and kidney diseases. Dietary risks in this age group contributed to deaths predominantly from cardiovascular disease.

Source: Global Burden of Disease. 2019

Mortality Rates by Cause

Cardiovascular Death Rate

Mortality rate from all cardiovascular diseases, ages 65+ years: In 2021, Wandsworth’s rate was 879.9 per 100,000 65+ (n=276), which was the 6th lowest in London, 13.9% lower than the England average and 13.4% lower than the London average. Time series data were not available for this indicator.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Respiratory Death Rate

Mortality rate from respiratory disease, ages 65+ years: In 2021, Wandsworth’s rate was 399.8 per 100,000 65+ (n=125), which was the 16th highest in London, 9.3% lower than the England average and 3.5% lower than the London average. Time series data were not available for this indicator.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Cancer Death Rate

Mortality rate from cancer, ages 65+ years: In 2021, Wandsworth’s rate was 920.2 per 100,000 65+ (n=289), which was the 12th lowest in London, 10.7% lower than the England average and 3.2% lower than the London average. Time series data were not available for this indicator.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Excess Winter Deaths

The number of excess winter deaths is linked to the outside temperature and the underlying level of disease in the population as well as other factors, such as how well-equipped people, and their environments, are to cope with the drop in temperature.

Winter mortality index (age 85 plus): In Aug 2021 - Jul 2022, Wandsworth’s rate was 22.4% (n=40), which was the 11th highest in London, 98.2% higher than the England average and 60.0% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for Aug 2021 - Jul 2022 was also 23.8% lower than in Aug 2001 - Jul 2002, in comparison with 55.2% decrease in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

2.3 Common Mental Disorders

The estimated prevalence of common mental disorders (CMD) in older people provides a valuable resource in the planning of preventative mental health interventions, such as psychological therapies. The indicator is designed to estimate local prevalence of CMD using national survey estimates for specific population cohorts and applying them to local demography.

Estimated prevalence of common mental disorders: % of population aged 65 & over: In 2017, Wandsworth’s rate was 11.4% (n=3474), which was the 16th lowest in London, 11.2% higher than the England average and 1.0% higher than the London average. Time series data were not available for this indicator.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

3. Falls, Frailty and Mobility

Ageing, as a ‘slowing down’ process 2, can turn simple activities into barriers that prevent a person from living healthily and safely in the community. As people age, it is likely that they will experience some degree of difficulty with activities of daily living (ADL) including:

- Mobility - the capability to move independently or with assistive devices around an environment3. In this chapter, having difficulties with one or more mobility tasks classifies as having issues with mobility. Tasks may include getting up and down the stairs, walking down the road, and moving around the house 4.

- Personal care - the completion of tasks to maintain personal hygiene, such as washing, toileting and administering medicines

- Domestic care–the activities to maintain a healthy living environment, including cooking meals and cleaning.

Due to the sequence of escalation, some older people may struggle to cope with domestic tasks yet are still able to be independent with their personal care. However, all the above can be exacerbated by issues with frailty.

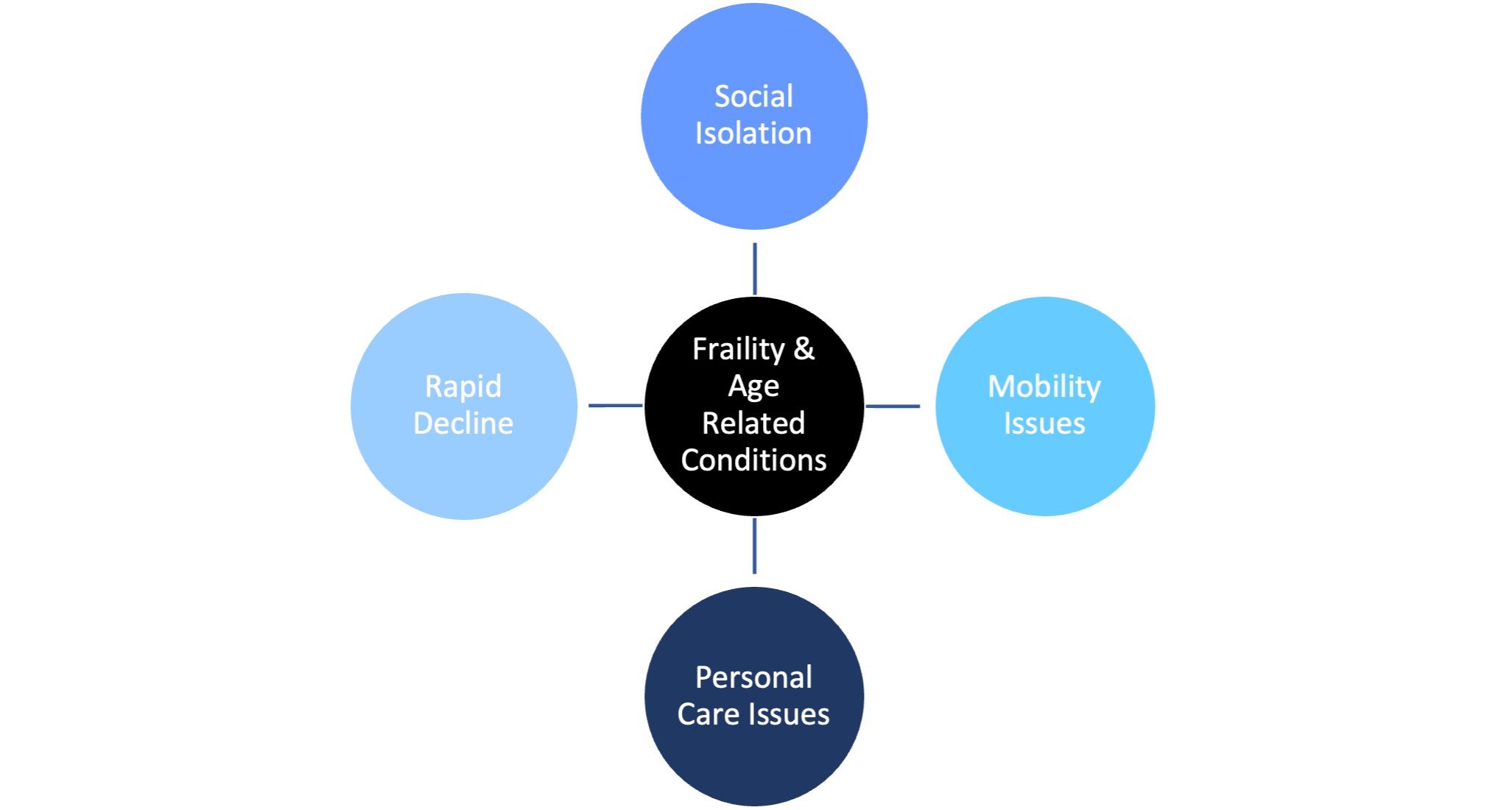

The ageing process presents a variety of challenges for older people from frailty, illnesses and age-related conditions, such as Dementia. As a result, some older people may have needs that require support from social care service, as they are unable to cope with basic self-care tasks.

Frailty is a state of low energy, slower walking speeds and poor strength5. It is not an inevitable consequence of the ageing process, however, prevalence rates for frailty do increase with age (figure below). Women are also more likely to be affected by frailty in comparison to men. The severity of frailty has also been found to increase dramatically in the year prior to death 6.

The impact of ageing and loss of independence may not only have a detrimental impact on a person’s life but also places strain on the overall health and social care system due to the need for costly and intensive support services. These services are underpinned by the statutory obligations outlined in the Care Act 2014. The Act places a duty on Local Authorities to promote person-centred care that acknowledges the physical, mental and emotional well-being of the person. The aim is to achieve this through strengths-based and preventative care and support services. This is because many age-related conditions that exacerbate mobility and personal care issues can be reduced, delayed or prevented by early lifestyle adjustments and interventions.

3.1 Falls

A fall is defined as an event which causes a person to, unintentionally, rest on the ground or lower level, and is not a result of a major intrinsic event or overwhelming hazard 7.

The human cost of falling includes distress, pain, injury, loss of confidence, loss of independence and mortality. Falling also affects the family members and carers of people who fall.

Financially, unaddressed fall hazards in the home are estimated to cost the NHS in England £435 million. The total annual cost of fragility fractures to the UK has been estimated at £4.4 billion which includes £1.1 billion for social care; hip fractures account for around £2 billion of this sum. Short and long-term outlooks for patients are poor following a hip fracture, with an increased one-year mortality risk of between 18% and 33% and negative effects on daily living activities such as shopping and walking 8.

As people get older, they are more likely to fall over. falls can become recurrent and result in injuries including head injuries and hip fractures.

Falls and fall-related injuries are a common and serious problem for

older people. People aged 65 and older have the highest risk of falling,

with 30% of people older than 65, and 50% of people older than 80

falling at least once a year 9.

Amongst older people living in the community, 5% of those who fall in a

given year will end up with fractures and hospitalisation. One in two

women and one in five men in the UK will experience a fracture after the

age of 50 10.

The causes of having a fall are often multifactorial and occur due to the presence of risk factors. Risk factors for falls include, but are not limited to, having a history of falls, muscle weakness, poor balance, visual impairment, polypharmacy, environmental hazards and a number of specific conditions ^{URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/falls-applying-all-our-health/falls-applying-all-our-health].

3.2 Hospital Admissions due to a Fall

Falls are the largest cause of emergency hospital admissions for people aged 65+, and impact on long term health outcomes of older adults; often resulting in people moving from their own home to long-term nursing or residential care.

Emergency hospital admissions due to falls in people aged 65 and over: In 2022/23, Wandsworth’s rate was 2187.4 per 100,000 (n=705), which was the 10th highest in London, 13.2% higher than the England average and 5.6% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2022/23 was also 12.0% lower than in 2010/11, in comparison with 9.1% decrease in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Emergency hospital admissions due to falls in people aged 65 to 79: In 2022/23, Wandsworth’s rate was 1197.7 per 100,000 (n=280), which was the 6th highest in London, 29.0% higher than the England average and 12.6% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2022/23 was also 10.4% lower than in 2010/11, in comparison with 10.5% decrease in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

3.3 Hip Fractures

Hip fracture, in many cases a result of a fall, affects mobility of older people–only around 30% of the affected people return to the levels of independence prior to the fracture and one in three ends up leaving their own home and moving to long-term care 11.

Hip fractures in people aged 65 and over: In 2022/23, Wandsworth’s rate was 507.8 per 100,000 (n=165), which was the 14th highest in London, 9.0% lower than the England average and 1.1% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2022/23 was also 11.7% lower than in 2010/11, in comparison with 9.3% decrease in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

3.4 Falls Services in Wandsworth

The Wandsworth Integrated Falls and Bone Health Service (IFBHS) was commissioned in 2012/13 needs. The IFBHS offered a holistic and preventative approach to falls which replaced the post-hoc falls management approach taken by prior services.

IFBHS is provided by St George’s NHS Foundation Trust and has the following aims:

- Reduction in the number of unscheduled admissions for people who have experienced a hip or other fragility fracture, due to falls

- Increase in the number of appropriate individuals people receiving a falls and bone health risk assessment

- Increase in the number of people in target groups undergoing an individually tailored community or home-based therapeutic exercise programme

- Increase in the number of people who are on appropriate medication and are adhering to medication advice.

- Reduction in the rate recurrent fragility fractures in the longer term

- Improved quality of life for people at risk of falls

- Reduction in the fear of falling

- Improved physical measures.

The service includes clinical staff (physiotherapists and occupational therapists) and group-based activities (e.g., Otago Falls prevention, Bone BOOST) delivered in the hospital or community settings.

3.5 Evidence Based Interventions in Falls Prevention

NICE and Public Health England lead on providing evidence-based guidance with regards to falls prevention, outlining approaches to interventions and activities helping to prevent falls and fractures in older people.

NICE guideline 12 recommends strength and balance training as part of an individualised multifactorial intervention. Those most likely to benefit are older people living in the community with a history of recurrent falls and/or balance and gait deficit. A muscle-strengthening and balance programme should be individually prescribed and monitored by an appropriately trained professional.

The National Falls Prevention Coordination Group’s Falls and fracture consensus statement (2017) advocates a collaborative and whole system approach to prevention, response and treatment 13. This includes:

- Promoting healthy ageing across the life-course

- Evidence-based case finding and risk assessment

- Evidence-based strength and balance exercise programmes and opportunities for those at low to moderate risk of falls

- Ensuring safe homes

- Demonstrating actions to reduce risk in high-risk health and care environments

- Fracture liaison services

- Evidence-based collaborative care for falls-related severe injury.

Interventions for older people living in the community with a low to moderate risk of falling should include strength and balance exercise programmes. These programmes are effective for primary and secondary falls and non-vertebral fractures in older people, but more effective for those who have a history of recurrent falls or who have a balance or gait deficit 14.

While there is evidence that walking has numerous health benefits for older people in general, it should not be included in programmes for participants considered at high risk of falling as this may result in further falls.

In order to be effective, programmes must:

- be continued over a duration of at least 50 hours

- be carried out two to three times a week

- challenge balance and improve strength through resistance training and exercise in a standing position

- be sufficiently progressive

- be tailored to the individual; pitched at the right level, taking falls history and medical conditions into account

- be delivered by specially trained Instructors.

At the end of the programme, older people should be assessed and offered a range of follow-on classes. These should suit their needs and abilities, include strength, balance, and support their progression.

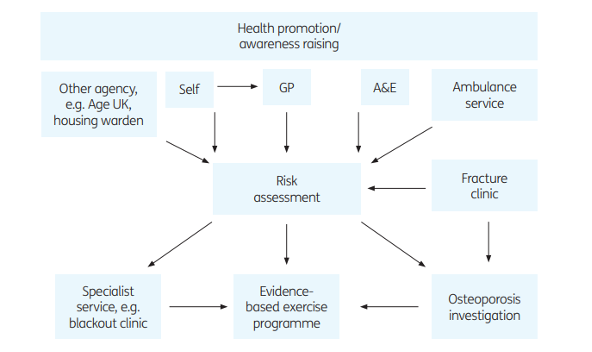

Falls prevention requires a collaborative and comprehensive approach (figure below) by the possible model of a falls prevention care pathway published by Age UK.

Source: Age UK

Age UK advise that services should offer a choice of and referral to an evidence-based exercise programme such as the Otago Exercise Programme or Postural Stability. For those who have not had a fall, effective exercise programmes can also include tai chi, dancing and other general exercise classes that include components of strength and balance 15.

There is evidence of cost-effectiveness for certain falls prevention interventions including:

- Falls Management Exercise (FaME) Group Programme

- Otago Home Exercise

- Tai Chi Group Exercise

- Home Assessment and Modification (HAM)–in which relevant professional risk assess a person’s usual place of residence to identify environmental hazards and carries out actions to reduce these.

A tool, commissioned by PHE, was developed to assess the return on investment (ROI) for these 4 programmes. The findings from this analysis indicate that all 4 interventions could be considered cost-effective when compared with usual care (i.e., no falls prevention service) in an English setting. It was noted that 1 out of the 4 interventions (home assessment and modification) should produce a positive financial return. For the remaining 3 interventions (Otago, FaME and Tai Chi) it was noted that, whilst not providing a positive financial ROI, there would be a positive societal return (i.e., improved quality of life) on the initial investment 16 17.

An internal falls prevention exercise evidence review (2019), carried out by Richmond and Wandsworth Public Health team, found literature to support Otago and Tai Chi. Evidence was found to support Tai Chi for reducing falls, or risk of falls, among elderly people, although, not for those who are frail. There was also evidence to suggest that alternative models of Otago in the community could be effective; although it was noted that further studies would be required to confirm and develop these findings.

Group-based exercise has been shown to be effective; however, this should be targeted group exercise that had been individually prescribed. Evidence also showed that home-based exercise could reduce the rate of falls the risk of falls, which could benefit those unable or reluctant to attend group classes.

Overall, the optimum approach for older people living in the community at risk of falling should include strength and balance exercise. Evidence-based exercise programmes recommended are FaME, Otago, and Tai Chi, and should be prioritised for consideration for local falls prevention exercise programmes. Other interventions reviewed provide benefits for strength and/or balance, such as dance, Pilates, yoga and Nordic Walking, but more research is needed to confirm their effectiveness in preventing falls among older people.

Falls prevention requires a multi-disciplinary, collaborative and whole-systems approach, with priority towards recognising individuals at risk and adopting a personalised yet multi-faceted approach to falls prevention.

4. Care and Support Services for Older People

When an older person finds themselves requiring care and support, they can arrange their care privately or through the Local Authority. The Local Authority will financially support people eligible needs and who are under the financial threshold. Care and support can either be provided in the community or in accommodation-based settings. Wandsworth Council will first explore the opportunities with community-based care as they enable the person to live independently in their own home. In turn, this helps the individual to build resilience and have more choice and control. Whether a person can receive care in the community, depends on their level of need. These services for older people include:

- Home Care

- Blitz Clean

- Delivered Meals

- Specialist Day Centre for Adults with Dementia

- Specialist Day Centre for Adults with A Physical Disability and Older People

- Open Access Centres

- Advocacy Services

- Community Equipment including Telecare.

An older person may require help with preparing food, cleaning, or personal care; therefore, an appropriate service would be delivered meals or a support worker to provide help at set times throughout the day. Additional support can also be provided through simple aids and equipment, such as walking frames, handles and washing aids, which can assist people to live independently in their own home to prevent accidents and personal neglect. This may also include the use of assistive technologies and Telecare. More complex needs can be supported through the Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) which funds housing renovations to accommodate changing needs, such as ramps, stairlifts and door widening. All these services help people to complete practical daily tasks, however, other day services are focused on wider wellbeing of the person.

Older people are encouraged to participate in the community through day centre provisions located across the Borough. Depending on the scope of the service, they can socialise, learn new skills and can access hot meals. For example, the Wandsworth Asian Women’s Association provides a drop-in service for Asian women in the community to attend a lunch club, socialise and obtain information on health and social care services. Some of the community services are run by the voluntary sector, such as the successful partnership with Age UK Wandsworth. Examples of their services include providing a befriending service to tackle the issue of social isolation; a shopping service to ensure that older people can remain safely in their own home and a handyperson service for ad-hoc tasks that may be difficult to complete as an older person 18. As Wandsworth Council works to align its services towards a prevention agenda, the role of the voluntary sector will continue to be of critical importance.

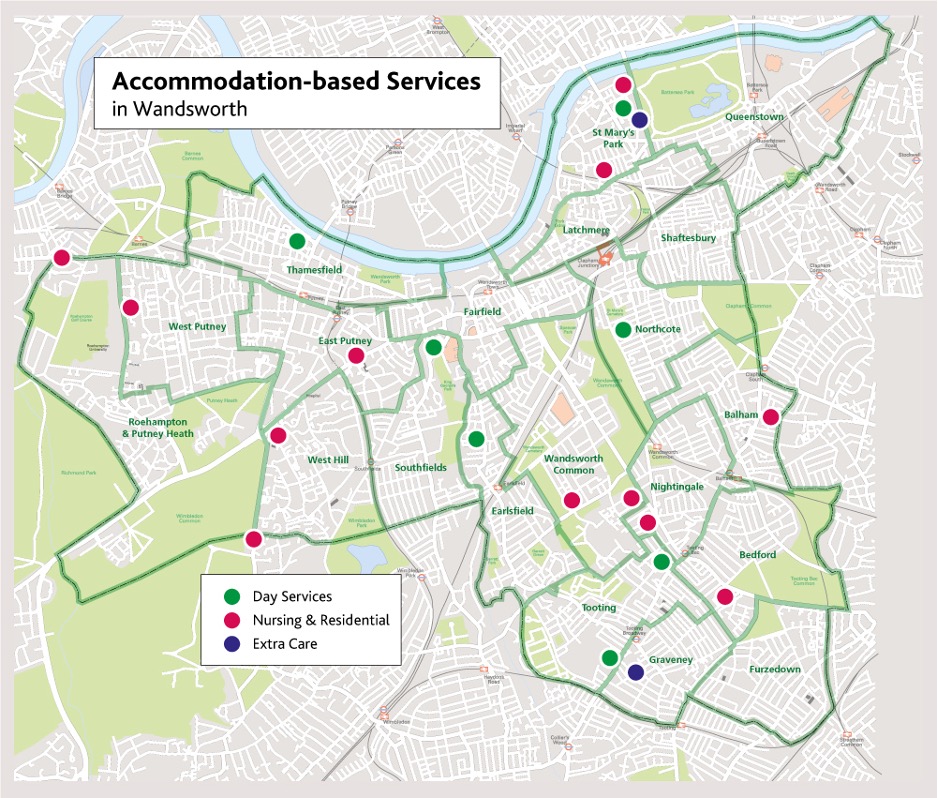

Community-based support is not safe or appropriate for all older people. Individuals with higher levels of need may receive more intensive accommodation-based services, which fall into three main types of services:

- Extra Care

- Residential Care

- Nursing Homes.

In Wandsworth, there are 8 commissioned residential homes, 16 commissioned nursing homes, 3 commissioned extra care schemes and 2 commissioned day services (see the figure below). Please note that this does not include services that Local Authority does not commission.

The services above for older people are either available for all older people or means tested depending on the type of service. For someone to receive accommodation-based and home care services they must meet the conditions set out in the Care Act and have less than £23,250 in capital/and or savings to receive council funded care and support services. However, the challenge to meet demand will continue to grow alongside the estimated growth in the population of older people, including those aged 85 years and over who have the highest care and support needs. Therefore, there will be a future unmet need in services for older people if service capacity remains the same as present levels.

Furthermore, Covid-19 has significantly impacted older people; the extent of which is not yet fully understood. For example, Covid-19 may impact on population predictions due to the higher death rates in 2020 of people aged 65 years and over. Many older people may be living with the symptoms of ‘long-term’ Covid-19. Furthermore, many older people may experience cognitive decline or mental health issues from having to live in isolation from other people. At this stage, it is unknown how far-reaching the impact of Covid-19 has been on older people; however, it is expected to be significant. Wandsworth Council will need to continue to support people by ensuring the aspirations of the Care Act 2014 are embedded into the care system and commissioning of services, considering the impact of Covid-19.

6. Vaccinations

Vaccination coverage is the best indicator of the level of protection a population will have against vaccine preventable communicable diseases. There are three vaccinations routinely offered to people aged 65 and over: seasonal flu vaccine, pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV) and shingles vaccine.

6.1 Seasonal Flu Vaccine

Population vaccination coverage: Flu (aged 65 and over): In 2022/23, Wandsworth’s rate was 66.2% (n=24881), which was the 15th lowest in London, 17.1% lower than the England average and 3.1% lower than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2022/23 was also 5.6% lower than in 2010/11, in comparison with 9.6% increase in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

6.2. Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine

Population vaccination coverage: PPV: In 2022/23, Wandsworth’s rate was 63.8% (n=22345), which was the 10th lowest in London, 11.2% lower than the England average and 5.0% lower than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2022/23 was also 7.4% higher than in 2010/11, in comparison with 1.9% increase in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

6.3 Shingles Vaccine

Population vaccination coverage: Shingles vaccination coverage (71 years): In 2022/23, Wandsworth’s rate was 45.9% (n=829), which was the 8th highest in London, 5.0% lower than the England average and 12.6% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2022/23 was also 4.5% higher than in 2018/19, in comparison with 1.6% decrease in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

7. Dementia Prevention and Care

This Dementia section builds on the 2019 Dementia Health Needs Assessment and provides a common view of health and care needs for local Dementia residents and their carers. It documents current service provision, identifies gaps in health and care services, identifies unmet needs, and details evidence of effectiveness for different health and care interventions. Furthermore, it draws on a wide range of quantitative and qualitative data to bring together information from different sources and partners to create a shared evidence base, which supports health and social care service planning, decision-making, and delivery. It can also utilise by other organisations, including the voluntary and community sector, to plan services that meet the needs of the local population.

Dementia is a progressive disease often associated with complex health and social care needs; these needs are expected to increase in Wandsworth, as a result of expected increases in numbers of older adults living in the Borough. There are several gaps and opportunities that should be addressed to improve the Dementia offer across Wandsworth. Therefore, enacting a comprehensive Dementia prevention and care support offer for residents affected by and living with Dementia remains a key focus for Wandsworth council alongside partners across the health and social care arena.

7.1 Definition of Dementia

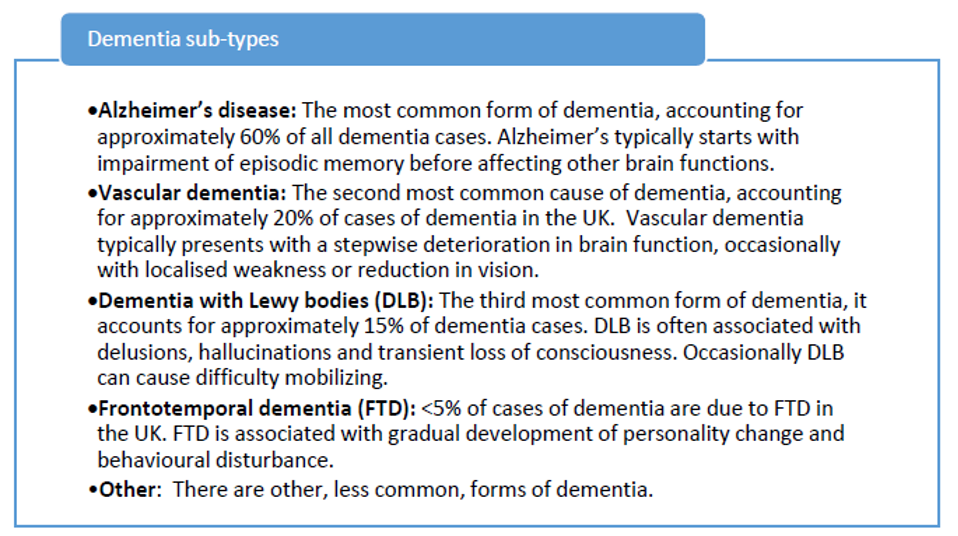

Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe a range of progressive neurological disorders (conditions that affect the brain). Although there are many subtypes of Dementia, the five most common are: Alzheimer’s Disease, Vascular Dementia, Dementia with Lewy Bodies, Frontotemporal Dementia, and Mixed Dementia. Some people may have a combination of different types of Dementia, and these are commonly called mixed Dementia 21.

Although often thought of as a disease of older people, around 5% of people with Alzheimer’s Disease are under 65. This is called early-onset or young-onset Alzheimer’s and usually affects people in their 40s, 50s and early 60s, with around 5% of people with Alzheimer’s Disease under 65 22. Early onset Dementia is caused by generally similar diseases to Dementia in older people (known as ‘late-onset Dementia’), but there are differences to note. There is a wider range of diseases that cause Young-onset Dementia, and a younger person is much more likely to have a rarer form of Dementia. Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of early-onset Dementia. However, there are other causes in younger people, such as Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) and much rarer causes such as Huntington’s Disease and Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) 23. A person with Young-onset Dementia may experience different symptoms from the memory loss usually associated with Dementia in older people. They could have, for example, problems with behaviour, vision, or language.

There is no cure for Dementia and the progressive deterioration that it causes results in high morbidity and, invariably, an earlier death for those afflicted with it.

7.2 Causes of Dementia

Dementia is not a single disease but is a term used to describe the symptoms that occur when there is a decline in brain function 24. As mentioned above, several different diseases can cause dementia (the figure below). Many of these diseases, such as in Alzheimer’s, are associated with an abnormal build-up of proteins in the brain. This build-up causes nerve cells to function less well and ultimately die. As the nerve cells die, different areas of the brain shrink. In vascular dementia, If the oxygen supply to the brain is reduced because of narrowing or blockage of blood vessels, some brain cells become damaged or die. In Dementia with Lewy Bodies tiny abnormal structures (Lewy Bodies) form inside brain cells. They disrupt the chemistry of the brain and lead to the death of brain cells 25.

Source: Dementia - NICE

CKS

Source: Dementia - NICE

CKS

7.3 Dementia in the UK

Dementia is associated with complex needs and, in the later stages of the condition, with high levels of dependency and morbidity and therefore is one of the major causes of disability and dependency among older people worldwide. This is the case not only for the people who have the condition, but also challenges for their carers and families.

In England and Wales, dementia accounts for every 1 in 8 deaths 26 making it the leading cause of death nationally. In 2018 it was estimated that there were around 850,000 people living with dementia, with this number expected to rise to over 1.6 million by 2040 27. Dementia therefore represents a significant current and, even greater, future challenge for all aspects of our society, with its effects being felt throughout not only the health and social care system, but also within communities, families and by individuals and their carers.

A national study 28 suggested that almost 7 in 10 people with dementia also have one or more other health condition. It reports that patients with dementia are more likely to have multiple health conditions. A total of 22% live with 3 or more comorbidities and 8% live with 4 or more comorbidities, compared to 11% and 3% respectively in the all-patient group.

The impact of dementia on health and wellbeing is significant and is progressively negative. The Alzheimer’s Society have reported that people fear Dementia more than any other disease 29. The loss of cognitive functions leads directly to reduced quality of life, increasing ill-health and early death for those living with the condition. A Dementia diagnosis, however, does not only impact the affected individual, but it also impacts their family, friends, work-colleagues, and the community; this impact can be physical, emotional, and financial.

Family and friends are often impacted through the need for provision of additional care and support for individuals with dementia, many take on the role of informal carers, carers that are not paid for their services. This results in additional personal strain for them but also loss of earning as they often must remain at home to care for their loved ones. Alzheimer Society estimates that the percentage of carers caring for more than 100 hours per week has increased from 40% to 50% since March 2020 30. In a wider context, Carers UK’s estimates that the average carer is now spending 65 hours a week on caring responsibilities 6[Behind Closed Doors, Carers UK (October 2020)].

The scale of the challenge that dementia poses to communities, local councils and national governments therefore is not to be underestimated, and it is for this reason that it has been identified as being the greatest global challenge for health and social care in the 21st Century 31.

7.4 Dementia Prevalence in Wandsworth

Dementia: Recorded prevalence (aged 65 years and over): In 2020, Wandsworth’s rate was 4.7% (n=1693), which was the 4th highest in London, 18.7% higher than the England average and 13.0% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2020 was also 4.5% higher than in 2017, in comparison with 8.3% decrease in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Estimated dementia diagnosis rate (aged 65 and older): In 2023, Wandsworth’s rate was 73.6 per 100 (n=1598), which was the 3rd highest in London, 16.8% higher than the England average and 12.2% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2023 was also 2.5% higher than in 2017, in comparison with 7.2% decrease in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

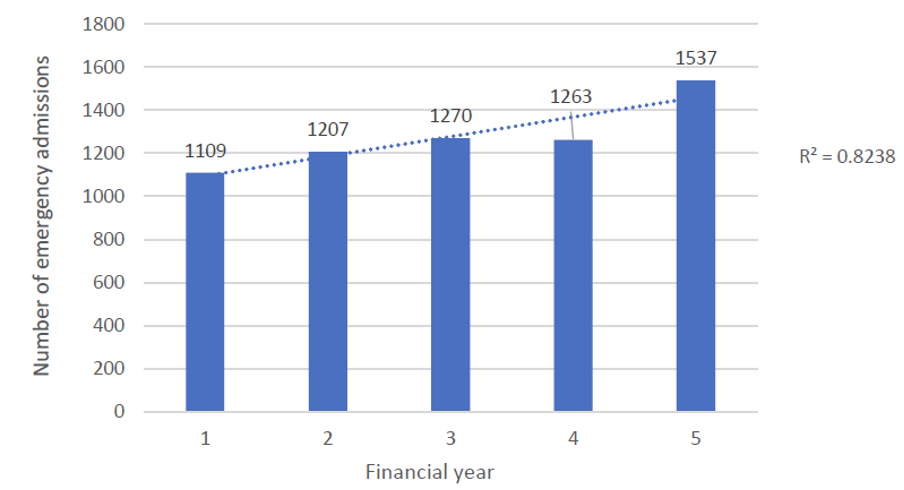

7.5 Emergency Admissions Linked to Dementia

Dementia: Direct standardised rate of emergency admissions (aged 65 years and over): In 2019/20, Wandsworth’s rate was 4820.4 per 100,000 (n=1515), which was the 7th highest in London, 37.0% higher than the England average and 20.1% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2019/20 was also 13.9% higher than in 2016/17, in comparison with 4.5% increase in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

7.7 National Policy Context for Dementia

Dementia is a national priority 32. There are many policy drivers for transforming dementia care, with a long-standing commitment in England to address dementia across all aspects of a dementia pathway; from pre-diagnosis to end of life care.

The first strategy of its kind, The National Dementia Strategy, ‘Living Well with Dementia’ (Department of Health, 2009) 33 was backed up by the Five Year Forward View, published in October 2014 34 which recognised dementia as a priority area. This further highlighted an aim to improve earlier diagnosis of dementia to slow the progression of the disease with treatment. To achieve this, the NHS Five Year Forward View focused on why there was a need for provision of a consistent standard of care for patients, improved support to clinicians and advisors and focus on proper care plans developed in partnership with patients and their families.

Following the publication of the Five Year Forward View, NHS England along with national partners launched a New Models of Care programme in 2015 35. The programme encouraged a more integrated care approach, which would present an opportunity to transform dementia care and support. Furthermore, the Next Steps NHS Five Year Forward update plan in 2017 36 focused on specifying what this integrated care model for dementia would look like within the established sub-regional Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships, as a mechanism to delivering the Five Year Forward Plan.

Building on the ambitions of both the National Dementia Strategy and the Five Year Forward View, the Department of Health’s Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 2020, further highlighted the importance of good dementia care, describing the need to improve recognition and quality of care for people with dementia and support for their carers. This included challenges to improve public awareness of dementia, ensuring health and social care staff receive appropriate training for their role, ensuring continuity of care and that any care package is ‘meaningful’ after diagnosis, as well as improving public awareness and understanding of dementia. Emphasis was particularly made on the role of communities in the form of “Dementia Friendly Communities” and on Local Authorities’ engagement with Dementia Action Alliances. Prime Minister’s Challenge was further supported by a call to action across all aspects of dementia diagnosis, care, and support from Department of Health’s publication, ’Dementia: A State of The Nation Report on Dementia Care and Support in England 37.

The Prime Minister’s Challenge also highlighted the continued need to expand the evidence base investigating dementia treatment and prevention through increasing capacity for ahigh-quality research into these topics.

In 2014 the Care Quality Commission published their themed review of care for people with dementia, Cracks in the Pathway 38, as they move between care homes and hospitals. They highlighted that quality of care for people living with dementia varies greatly across England and raised a need for reducing such variability, ensuring that the personalised approach, knowledgeable staff, for people living with dementia is available throughout England’s health and care system.

NICE have also provided a range of guidance on dementia, including Quality Standards for Supporting People to Live Well with Dementia 39, guidance with recommendations for the identification, treatment, and care of people with dementia. NICE emphasized the principles of a person-centred approach 40; it also published a guidance covering mid-life approaches to delay or prevent the onset of dementia, disability, and frailty in later life, to increase the amount of time that people can be independent, healthy and active in late life 41.

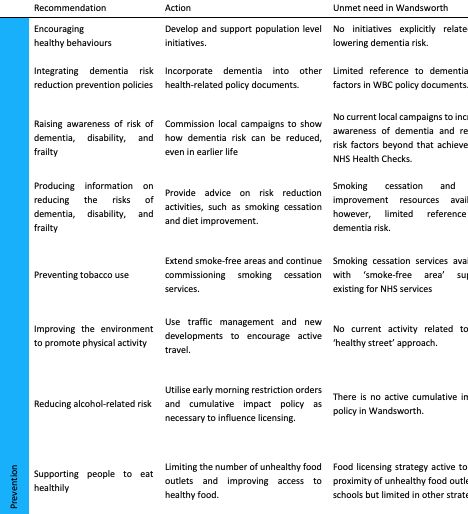

There have been many other policies and guidelines in place to improve health and promote healthy behaviours within the population; however, it has not often been clearly stated that by improving individual’s health reduces the risk of dementia, disability, and frailty. Therefore, the role of Local Authorities was further highlighted by Public Health England (PHE) in 2018 which emphasised their critical role in reducing dementia risk as well as the overall societal impact through the promotion of healthy lifestyles, age and dementia friendly built environment approaches, maximising signposting opportunities and promoting opportunities to improve cardiovascular health through the “what’s good for your heart is good for your brain” campaign.

The NHS Long Term Plan 42 published in 2019, commits to further improving the care for people with dementia, with the aim to improve the care provision to people with dementia, whether in hospital or within the home setting. It re-emphasised the focus on dementia by including it in its “biggest killers and disablers of our population” list, with promotion of an increased focus on community multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) to provide care in the community to retain independence of people living with dementia.

7.8 Local Policy Context for Dementia

Although, there is no strategy specifically designed to address dementia needs in Wandsworth, there are multiple plans or policies in which Dementia and Dementia-related care are considered in the table below. Overall, the policy context in Wandsworth describes a recognition of people with dementia and their unpaid carers; in addition to acknowledging the need for improved service accessibility in the Borough, whether that be access to medical care, housing, or social activities.

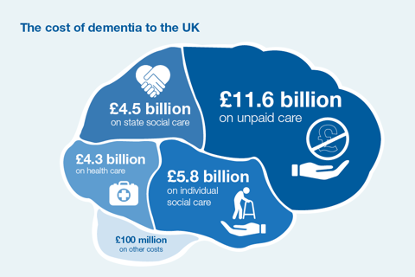

7.9 The Economic Impact of Dementia in the UK

Annually, the direct healthcare cost of dementia in the UK is estimated to be approximately £26 billion, the equivalent of £32,250 per person per year. As expected, social care costs account for a significant portion with £5.8 billion being private funded by individuals (23% of total cost) and the rest, £4.5 billion by the state (the figure below). More than half of these costs, however, come from unpaid care, which is valued at £11.6 billion; however, this may well increase in future, as more people leave employment to undertake care activities. The cost of this early loss of employment is estimated to be around £3 billion by 2030 43.

Approximately 25% of hospital beds are occupied by people living with dementia. Their length of stay is often longer than of people without dementia; the delays in supporting people with dementia to leave hospital are also more frequent 44.

Source: Public Health England Guidance: Health matters: midlife approaches to reduce Dementia risk, 2016 45

7.10 Risk Factors for Dementia

The risk of developing dementia is associated with a mixture of factors–some which can be avoided (modifiable risk factors) and others that are virtually impossible to control (non-modifiable risk factors).

The risk of developing dementia can be affected by lifestyle, by genetics, vascular reasons or drug and medicine related 46. It is estimated that more than a quarter 28% of the British public cannot identify potential modifiable risk factors for dementia and only 2% could identify any of the following risk factors: heavy drinking, smoking, high blood pressure, depression, and diabetes as well as the protective factor of taking regular exercise. This is despite that 59% of people know someone with dementia 47.

Non-modifiable Risk Factors for Dementia

These are risk factors that as the name implies, cannot be changed as they are inherent in each person.

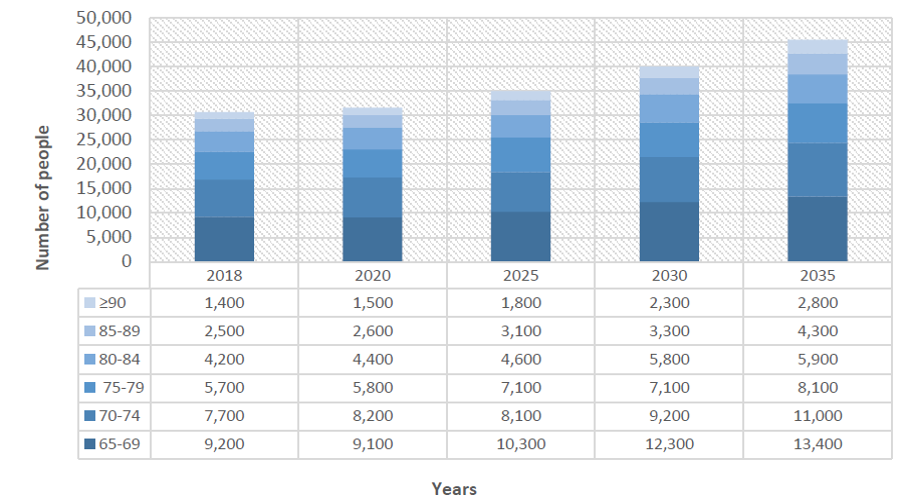

- Age: Age remains as the single biggest and non-modifiable risk factor for dementia with a person’s risk doubling approximately every 5 years 48 above the age of 65. In Wandsworth there are currently estimated to be 30,744 residents ≥65, accounting for 9.7% of the total Borough population. It is estimated that this number is to increase by 87% to 57,622 residents by 2050 (the figure below - up to 2035 only)

- Gender: Alzheimer’s disease is more common in women than men, even after accounting for the greater life expectancy in women. This association is not seen for other dementia types (e.g., vascular, LBD or FTD). This is reflected in Wandsworth where 62.6% (1,318) of dementia patients ≥65 are women, even though women make up 56% (17,500) of the total ≥65 population. In terms of a wider impact, women are far more likely than men to end up as carers of those with dementia. Women are also more likely to reduce their hours or stop working to care for someone with dementia, and some feel penalised at work for taking on care responsibilities

- Ethnicity: The Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) have estimated that more than 25,000 older black and minority ethnic (BME) people live with dementia in the UK. Further research suggests that South Asian, African, or Afro-Caribbean ethnic groups have higher rates of dementia than other ethnicities 49 due to an increased rate is thought to be due to the higher prevalence of high blood pressure, diabetes, and strokes within these ethnic groups. This is particularly relevant in Wandsworth where 25.26% of the population identify as black, Asian and mixed ethnicity (BAME), based on the 2011 Census. In 2016, 40.7% of people, who died in Wandsworth with dementia being identified as the underlying cause, were born outside of the UK 50

- Other: Learning disabilities, particularly Down’s Syndrome, significantly increase the risk of developing dementia and earlier onset dementia. In 2016/17 there were 1,205 people, known to their GP, affected by learning disability in Wandsworth. People with Down’s Syndrome are most likely to develop dementia linked to Alzheimer’s disease. However, there is a growing awareness that people with Down’s Syndrome can also develop other forms of dementia 51

Source: Wandsworth Dementia Health Needs Assessment, 2019

Although there is no evidence to suggest that sexual orientation is a risk factor, the experiences of living with dementia in the lesbian ,gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community need to be taken into consideration. LGBT communities are affected by dementia both as patients but also as unpaid carers. Using national prevalence rates for dementia it is estimated that 5–7% of the population is LGBT, thus over 34,000 LBGT people living with dementia nationally. The Alzheimer’s Society estimates that between 35,000 and 70,000 LGBT people care for a person with dementia in the UK. Therefore, people from this community face additional challenges in terms of getting appropriate support and understanding. This may be finding appropriate residential care in later stages of the disease or accessing Support Groups in early stages where other older people are comfortable discussing same sex partnerships. Estimates of the prevalence and incidence of gender dysphoria and transsexualism are difficult to quantify due to the lack of robust national data. It is accepted that gender dysphoria, if not treated, can severely affect a person’s quality of life and health status. High levels of depression are reported within trans communities, therefore indicate that this population group may require greater access to support. The Alzheimer’s Society consider that as dementia progresses a person may not recall their current gender and they may see themselves being pre-transition and be surprised at the physical changes to their bodies. It is therefore important that the specific needs of transgender Dementia patients are addressed appropriately. The Alzheimer’s Society provide advice on dealing with the impact of dementia on disclosure. Patients may have to make decisions on a day-to-day basis about whether to disclose their sexual orientation or gender identity–whether to be ‘out’. As dementia progresses, patients may lose their ability to make this decision. They may also be unable to stop themselves disclosing their orientation or gender identity by mistake.

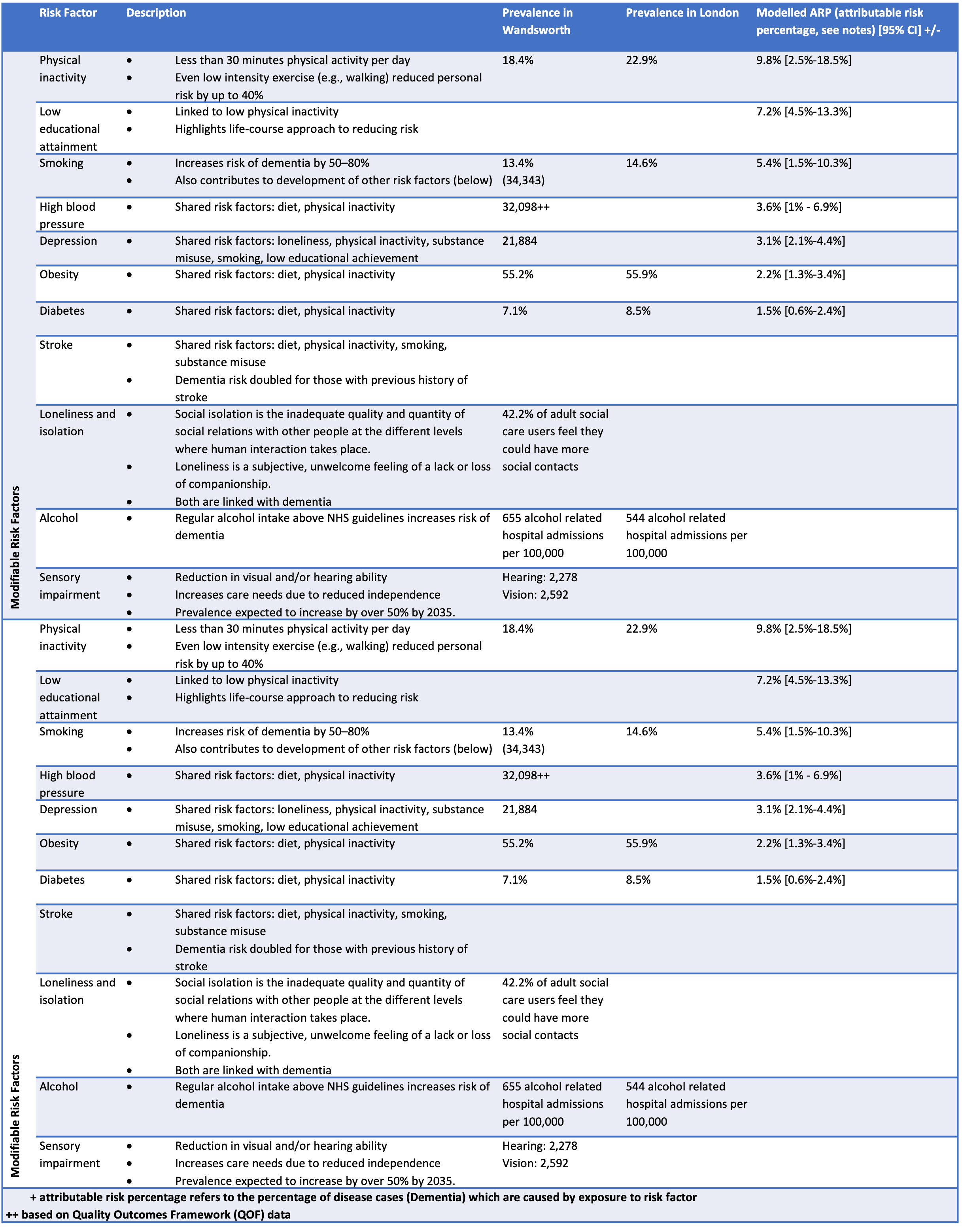

Modifiable Risk Factors for Dementia

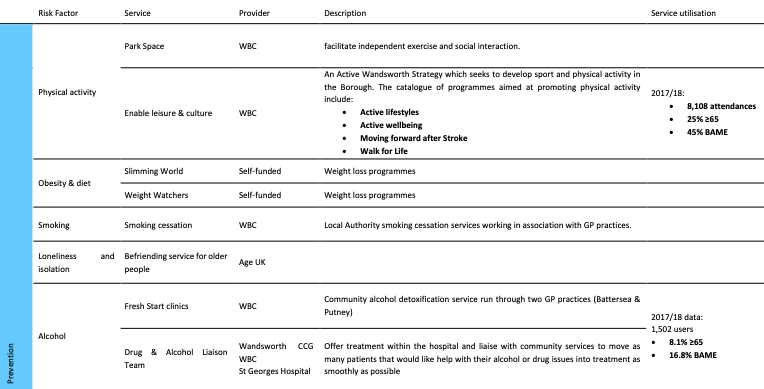

There are also modifiable risk factors (the table below) of treatable medical conditions and lifestyle choices that play a role in developing dementia. These risk factors are partially in control of the individual, family, or community and, therefore, are the focus of many interventions. Recent studies have determined that improvements to lifestyle habits and management of comorbidities may lead to a lower risk of dementia. Management of cardiovascular risk factors (such as diabetes, obesity, smoking, and hypertension) and participation in regular physical activity, can reduce the risk of cognitive decline and may reduce the risk of dementia.

Health inequalities are exacerbated by the circumstances and environment in which we live, and often these health inequalities tend to persist into old age. There is a growing evidence that many of the modifiable risk factors for dementia are indirectly associated with socio-economic disparities in mortality and morbidity. For example, there is a strong link between cigarette smoking and socio-economic group 52. Smoking is one of the biggest modifiable risk factors for dementia doubling the risk of developing the condition. There is also evidence that low socio-economic position can result in lack of physical activity, another risk factor for developing dementia 53. The socio-economic circumstances can have a major effect on physical and mental health and can create or close off the opportunities to make healthy choices 54.

7.11 Evidence Based Interventions in Dementia

Dementia is currently incurable and the number of symptomatic treatments available are limited. However, dementia research is a key element of the Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia. PHE Dementia Intelligence Network is tasked with collating new and existing data on dementia enabling public health agencies to have a better understanding of prevalence and how it affects the population. Significant improvements were made over the recent decades in making more readily available treatment options; this as well as widespread dementia screening in routine assessments will result in a more ‘dementia-friendly’ clinical culture and society.

Both secondary and tertiary prevention strategies have benefits to those living with dementia, by slowing progression and improving quality of life; therefore, maintaining an individual’s independence for longer 55. The WHO published guidelines for the risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia, whereby most of the recommendations align with current guidelines for the treatment of pre-existing health conditions and dependencies in the UK. For example, for cognitive outcomes in healthy adults, WHO identified physical activity interventions to have a positive effect on cognition and interventions for tobacco cessation may reduce the risk of cognitive decline and dementia, in addition to other health benefits. The report also recommends a healthy, balanced diet. However, much is still unknown about the long-term effect of treatment of older people and prevention through risk factor reduction 56.

Further evidence of good practice can be drawn from a Good Practice Compendium (2011) 57, which demonstrates how local delivery of the National Dementia Strategy can be supported, to improve outcomes for people with dementia and their carers. Similar content can be found in recent Alzheimer’s Society report published October 2020 58. Some of the evidence-based recommendations are included below, across the whole dementia journey.

7.12 Preventing Dementia

NICE recommends that national organisations and any local government department that influence public health, should develop and support initiatives to reduce the risk of dementia. Prevention and slowing of progress remain the mainstay of dementia management. A range of interventions have been suggested to be useful in supporting people with dementia to slow the progression of the disease and maintain their independence for longer 59 through promoting healthy lifestyles. These include encouraging healthy behaviours (reducing smoking, increasing physical activity, reduce alcohol intake), achieving and maintaining a healthy weight and adopting a healthy diet.

Prevention is better than cure and in dementia more so than in other disorders does this ring true. Although, we cannot influence the most significant risk factor (age), key interventions aimed at influencing and reducing cardiovascular risk, improving physical and mental health, addressing social isolation and loneliness 60 and combating drug and alcohol abuse are important avenues in dementia prevention. The Blackfriars consensus published in 2014 61 acknowledged that sufficient evidence exists, with which people can be empowered to reduce their risk of dementia through reduction of cardiovascular disease risk and improving brain health. In addition, there is evidence that stimulating cognitive functions throughout the life cycle is associated with reduced risk of dementia 62. Cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) is a brief treatment for people with mild to moderate dementia involves taking part in group activities and exercises designed to improve memory and problem-solving skills.

7.13 Diagnosing Dementia

Referral to dementia specialist diagnostic services ensures that a diagnosis is both timely and accurate. Different types of dementia can be identified quickly to ensure targeted and tailored support is in place in a timely manner. Memory Assessment Services (MAS) are recommended by NICE guidance43 as a single point of referral for early diagnosis of dementia. They can be provided in several different settings, including a psychiatric or general hospital, as part of community mental health services or in primary care. This single point of access can then act as a lever for further investigation of dementia sub-types.

Support Following a Diagnosis of Dementia

The Department of Health published guidance on what to expect from health and care services for those who are recently diagnosed with dementia, outlining the different stages of support a person and their carer may require; it is also a good building block for identifying what is good practice 63. NICE guidance indicates that service provision should ensure that people living with dementia have ‘equivalent access to diagnosis, treatment and care services for co-morbidities to people who do not have dementia’. There is associated NICE guidelines on multi morbidity 64 and older people with social care needs and multiple long-term conditions 65.

Care Planning

The use of care plans is recognised by NICE as a method of empowering patients to maintain their own independence following a diagnosis and is particularly relevant in Wandsworth, given that there is large variation in meeting care planning QOF targets; with performance of GP practices ranging from 66.7% to over 90%. Care plans should be drawn up and reviewed annually in face-to-face meetings with GP’s and should consist of the following core “D.E.M.E.N.T.I.A” components 66:

- Diagnosis Review

- Effective support for Carers Review

- Medication Review

- Evaluate risk

- New symptoms enquiry

- Treatment and Support

- Individuality

- Advance Care Planning.

Hospital Care

The NICE guidance on Dementia also addresses the transition from hospital to community settings (be it at home, or a care home setting) for adults with social care needs, which include the quality-of-care people should expect when they are admitted and discharged from hospital. This includes involving people in their own care planning.

An example of good practice within the hospital setting is having a multidisciplinary team that links directly with community services, to avoid unnecessary admissions. This drives a ‘home first’ approach, based on recognising that patients, being in their familiar environment whenever possible, optimises patient recovery and delivers better outcomes. One example of this is the ‘therapy at the front door’ initiative, which is a tactic that brings therapists into Accident and Emergency. Senior therapists identify and assess patients with frailty, who can then be discharged on the same day or may only require a short admission. By carrying out a risk assessment, they can immediately arrange rapid support to keep the patient safely at home.

Non-pharmacological Support

Non-pharmacological techniques, such as cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) are also offered to dementia patients. CST is recommended by NICE for mild to moderate dementia whereas CBT is often used for those who are also experiencing depression and anxiety.

Pharmacological Interventions

The mainstay of treatment for dementia is improving quality of life and maintaining independence for as long as possible. For some forms of dementia, pharmacological (medication) is available in the early stages. A range of pharmacological interventions have been linked to support treatment and prevention of cognitive and behavioural conditions related to dementia 68. Dementia treatment options remain limited, with known dementia treatments diminishing in efficacy after the first few years.

7.14 Ensuring Quality of Life with Dementia

There is a wealth of evidence of good practices in provision of support and care for people with dementia and their carers to maintain independence for as long as possible. The following are examples of interventions to promote cognition, independence, and wellbeing:

Dementia Friendly Communities and Organisations

Dementia Friendly Communities (DFC) and Dementia Friendly Organisations (DFO) have become widely accepted in local and national policy as playing an important role in improving the lives of people with dementia. In 2014 Public Health England (PHE) and Alzheimer’s Society launched a major campaign promoting Dementia Friends [URL: www.gov.uk/government/news/new-Dementia-campaign-launches-as-research-reveals-the-true-cost-to-business-of-Dementia].

The Alzheimer’s Society defines a DFC as: “a city, town or village where people with dementia are understood, respected and supported, and confident they can contribute to community life. In a dementia friendly community people will be aware of and understand dementia, and people with dementia will feel included and involved, and have choice and control over their day-to-day lives” 69.

Both the LGA 70 and The Alzheimer’s Society have also published criteria and guidance on what should constitute a Dementia Friendly Community or Dementia Friendly Organisation and best practice. Criteria include good access to community services, such as befriending and engagement services and adjusting the practicalities of daily life, such as housing, travel, and local businesses to be dementia aware, responsive, and respectful.

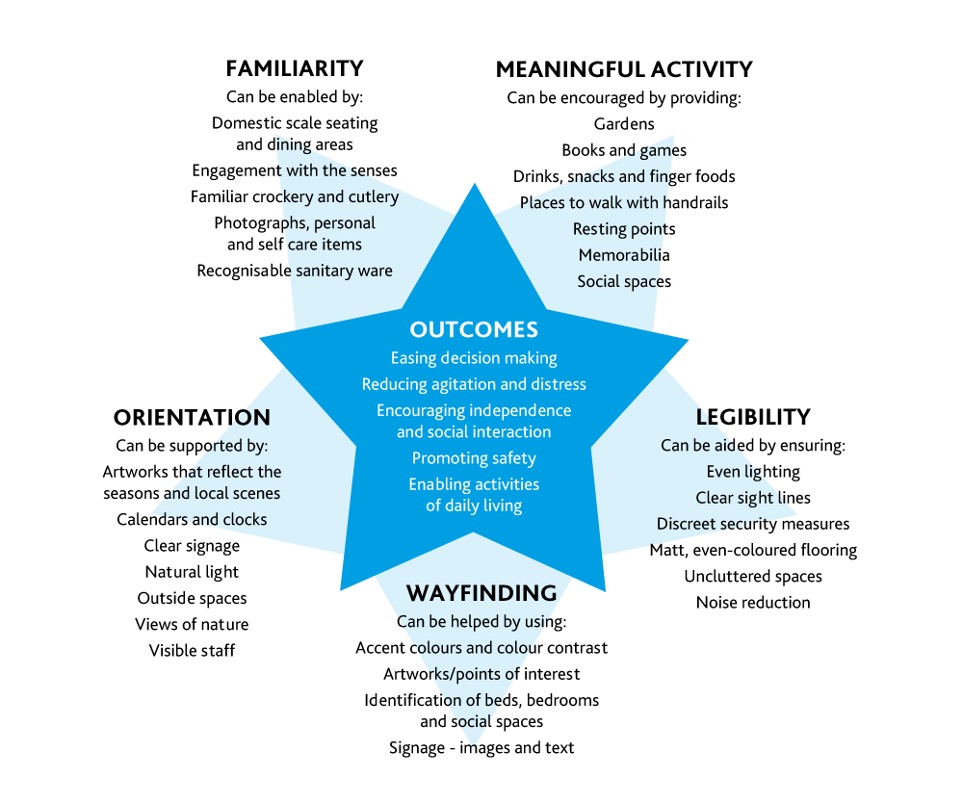

The Kings Fund, as part of their Enhancing the Healing Environment series, have published self-assessment tools in 2014 and updated in 2020 for housing, care-homes, health centres and hospitals (the figure below). The tool assesses 7 domains, providing a score, which reflects the “friendliness” of the setting to those with dementia. The care home assessment tool 71 is particularly relevant to Wandsworth, as CQC findings report that nearly half of care homes in Wandsworth require improvements 72.

Source: The Kings Fund ‘Is your care home Dementia friendly?’: EHE Environmental Assessment Tool Domains. 2020 (redesigned)

Dementia Champions

Championing the dementia cause is needed across a range of settings. Skilling up staff through dementia awareness training on the signs and symptoms of dementia can contribute to staff becoming more responsive to dementia needs, lead them to a better understanding of the issues related to the disease and championing the dementia agenda.

Peer Support and Dementia Cafes

Research shows that people with dementia express is the need to stay connected to their families, friends and communities and be able to engage in activities that they enjoy. Unfortunately, some community groups find it difficult to accommodate people with dementia.

The National Dementia Strategy promotes the establishment and maintenance of local peer support networks for people with dementia and their carers. These types of initiatives 73 are also supported by the Prime Minster challenge37. Furthermore, the Care Act 2014 ^[[GOV.UK. Care Act 2014. URL: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/contents/enacted] stipulates that improvements are required in delivering early interventions from care and support systems to support individuals to retain or regain both their skills and confidence, and to prevent or delay deterioration wherever possible. Additionally, NICE guidance recommends people are signposted to support groups post-diagnosis and their carers have access to peer support opportunities. The Health Innovation Network produced a resource pack to bring together examples of good practice and evidence-based guidance on peer support, to help groups and organisations better support people with dementia in their communities.

Assisted Technology

There has been a great deal of promise in how assisted technology, ‘electronic’ or ‘intelligent’ assistive technology, may help address the individual, family and societal challenges presented by dementia, and to support people with dementia to live more independently and, ideally, with improved quality of life in a cost-effective way. The challenge is that there is no real evidence available that can confirm such claims and more robust evaluations helping to understand what works, for whom and how are needed as well as the impact of these technologies in the context of dementia 74 75.

Supporting Carers

Carers of people with dementia face additional challenges to ensure that their own physical and mental health needs are being recognised and met, both because of the demands of the caring role, but also because of difficulties with accessing support. It is essential that carers have good support to enable them to manage the stresses and demands of their caregiving. NICE guidelines recommend that services make provision for carers to be supported in their roles 76. Informal carers are particularly important, given the significant contribution they make to the people they care for but also to the community. Nevertheless, informal carers are also at risk of personal psychological and psychosocial distress, which must be monitored, identified, and managed promptly. Evidence of good practice in supporting carers include offering education and skills training to carers. Some carers may require their own care plans to address their needs too, which can include, but not be limited to, psychological therapies (e.g., CBT), peer-support groups, training courses and respite care.

7.15 End of Life Care and Dementia

People with dementia have the same right to a good death as people with other health conditions. The Department of Health (2008) indicates that a good death would involve being treated as an individual, with dignity and respect, without pain and other symptoms, in familiar surroundings and in the company of close family and friends. However, it has been reported that often, people with dementia do not receive this level of dignified care and treatment, resulting in people with dementia not being referred for specialist end of life care, receive inappropriate treatment and, in some cases, ending their lives in pain 77.

There are quality standards that cover the clinical care of adults (aged 18 and over) who are dying, both during the last 12 months of their life 78, and during the last 2 to 3 days of life 79, which are supported by The Alzheimer’s Society that advocate a need for advance planning for end of life care, with improvements needed in the co-ordination of a good death, ensuring that health and social care professionals are trained in providing high-quality, person-centred care to improve dignity and quality of life, even when communication has declined.

The digital care planning service ‘Coordinate My Care’ (CMC), facilitates electronic sharing of urgent care plans between healthcare providers, including the London Ambulance Service (LAS) to enable sharing of core information such as preferred place of death, cardiopulmonary resuscitation status, advice regarding ceilings of care and other patient preferences.

7.16 Community and Stakeholder Views on Dementia

On a national level, the Dementia Attitudes Survey carried out by Ipsos MORI for Alzheimer’s Society 80 shows that, despite public awareness of dementia being relatively high, the range of symptoms of dementia are not as fully understood by the public, which has also very limited knowledge of the breadth of people, who are affected by dementia. There is a general misconception of dementia being a condition of old age rather than a cause of death, as well as a low level of understanding of risk factors that affect dementia. This contributes to a reduced recognition of ‘physical contributors to dementia risk compared to factors like less mental activity, loneliness, depression and stress’. The survey also identifies that the public want to know more about their brain health, especially within the younger and mid-life generation, to plan for future support and care.

There is public support for research into cure and prevention more so than research on improving quality of life for those affected with dementia, which demonstrates an appetite for increased knowledge on preventative action. The Dementia Attitudes Survey 81 also highlighted the importance of culturally sensitive messaging and support in future campaigns that should be informed by input from BAME communities.

7.17 Prioritising Dementia in Wandsworth

The 2019 Dementia Needs Assessment found that five years ago, the dementia prevalence in Wandsworth was lower than both regional and national averages. However, due to a high local incidence rate, prevalence in the Borough is increasing faster than elsewhere.

There are 12.6 new diagnoses of dementia per 1,000 people aged >65 per year in Wandsworth each year, a significantly higher rate than the London (10.3 per 1,000) and England (11.1 per 1,000) average 82.

As of January 2019, 1,719 people aged over 65 on Wandsworth GP registers had a diagnosis of dementia, accounting for 5.4% of the total Wandsworth ≥65’s population. This figure climbs to 2,158 (6.8% of the ≥65’s population) if estimates of those living with undiagnosed dementia are added. There was a total of 1,774 patients (including under 65) with a diagnosis of dementia 83.

Based on these prevalence figures and 2012/13 average dementia care cost prices, the total cost of dementia in 2019 for Wandsworth is estimated as £70.4m, of which £27.3m is attributable to social care and £11.6m to healthcare costs. Importantly, given that there is expected to be a 47% increase in the number of people aged ≥65yrs affected by dementia by 2035, the costs associated with care for this cohort of patients is likely rise more steeply. There is also a wider system pressure on activity and finances; for example, Wandsworth has a falls history recorded for 42% of patients of the memory clinic, indicating an additional pressure on health and care resource, time, and expertise across the wider system.

One of the reasons that Wandsworth Borough Council considers dementia a priority is because the rate of increase can be decreased with effective reductions in dementia risk factors; with current evidence suggesting that up to 30% of the most common forms of dementia can be prevented or delayed simply by addressing these risk factors. A delay of 2 years in dementia onset can result in a 22% reduction in costs by 2050 with a 5-year delay resulting in a 36% reduction in costs 84.

Additionally, slowing dementia progression also reduces the severity of disease for patients. Compared to baseline (normal progression) a delay in dementia progression by 25% would reduce the number of severe dementia cases in 2050 by approximately 43%, whereas a 50% slower rate of disease progression would reduce this by approximately 86%.

Early Onset Dementia

Amongst those aged under 65 on Wandsworth practice registers, dementia prevalence is 1.58 per 10,000. (n=58). This is significantly lower than prevalence in London (2.28 per 10,000) and England (3.41 per 10,000). Dementia affecting those under 65 years accounts for 3.3% of dementia cases in the Borough.

Dementia and Ethnicity

Regarding recorded dementia diagnosis by ethnicity, the data may not be as accurate, as many ethnicities have not been defined in reporting. For example, in Wandsworth, as of January 2019, 238 of dementia patients had their ethnicity recorded as white, 139 as Asian or Asian British, 41 of mixed or multiple ethnic groups, and 16 defined as ‘other’ ethnic group. No ethnic reporting was recorded for Black or African or Caribbean or Black British, however, most of the reporting did not define ethnicity (n= 1191). Therefore over 70% of people with a diagnosis of dementia in the Borough of Wandsworth do not have their ethnicity recorded. Consequently, whilst these figures may rationalize further investigation, they should be interpreted with extreme caution.

Referrals for the Memory Assessment Service (MAS) also records ethnicity when agreed or provided by the service user, but again, these figures should be interpreted with caution. The current MAS caseload as of May 2020 reported 45.6% as White 17% as Asian, 1% mixed or multiple ethnic groups, 3.7% as ‘other’ and 12.4% recorded Black or African or Caribbean or Black British. 18.2% did not answer and 1% left the answer blank. As data on the Borough ethnicity is as it was in 2011, it is difficult to draw conclusions about any discrepancy between expected and actual referrals for the BAME community to the MAS clinic, as this data would not be relevant to the existing dementia referrals as of 2020. The MAS caseload data was included in the national census, March 2021.

Dementia in Relation to Comorbidities

Rather than being the primary reason for emergency admissions, dementia is most often a secondary or tertiary diagnosis in Wandsworth, emphasizing dementia’s relationship to comorbidities . Although there is inconsistent primary care provision within care homes, there are dementia specialist nurses available in the Borough to support the recognition of mismanaged comorbidities.

Geographic Variation

Due to differences in population size and case finding practices between GP’s, obtaining accurate data regarding the geographic prevalence of dementia diagnoses is difficult. Nevertheless, some over-arching themes have been identified through triangulation of data from Primary Care, Adult Social Care (ASC) Services and ward demographic profiles.

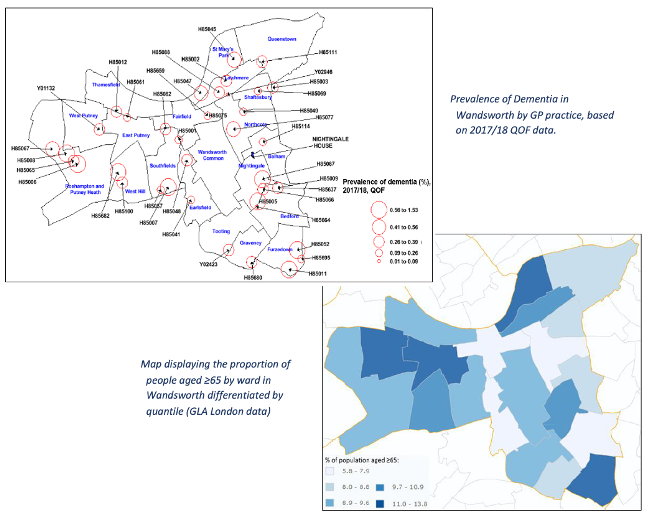

Generally, dementia prevalence is higher in southern and western wards of the Borough, reflecting the higher proportion of ≥65 residents who live in those areas. Wards such as Nightingale and Furzedown in the South, and West Putney and Roehampton and Putney Heath in the west all having relatively high prevalence rates. Of note, is that Nightingale has the highest prevalence of dementia out of all London wards at 1.5%, which is linked to having a number of care homes located in the area (the figure below). The size of this intra-borough variation, in both disease prevalence and risk factor prevalence, highlights the importance of considering geographic location when allocating resources related to dementia.

Residential Status of Dementia Patients

Having dementia does not mean that people cannot live independently. Dementia UK estimates that 63.5% of people with late onset dementia live in their own home. Local data from 2017/18 showed that 80% of ASC users with a documented dementia diagnosis lived in the community, a reduction from 89% from the previous year 85.

Estimates based on the expected dementia prevalence in these care settings suggests that Wandsworth residential homes and nursing homes have 259 and 179 residents respectively who are living with dementia which is either unrecorded for ASC purposes, or undiagnosed. This highlights a need for either improved completeness of data collection, or for improved access to diagnostic services in care homes in the Borough, or both.

754 people received Wandsworth Adult Social Care Services in 2017/18, of whom only 6% (45) had dementia documented in their MOSAIC record, this is lower than national and expected figures 86. A total of 479 people were in residential accommodation, 277 of them are estimated to be living with dementia but only 18 had a dementia diagnosis recorded on MOSIAC. This leaves a gap of 259 unaccounted cases (Diagnosis rate = 6.5%). In nursing accommodation, of 275 residents, 201 were estimated to be living with dementia but only 27 had a dementia diagnosis recorded on MOSAIC, leaving a gap of 174 counted cases (Diagnosis rate = 13.4%).

The low dementia diagnosis rate in care homes in Wandsworth may have previously been attributable to the reduced attention to non-urgent conditions in the context of large homes using weekly (or less frequent) primary care ward rounds. The low diagnosis rate in Wandsworth could also be due to inconsistent documentation of confirmed diagnoses in the social care system, rather than a true diagnostic gap and this needs further exploration.

Emergency Admissions

Although not usually a primary reason for admission, dementia is often a secondary or contributing factor in unplanned hospital admissions amongst the elderly. The increasing numbers of people with dementia living longer has resulted in a significantly higher likelihood that they will require care in acute hospitals.

In 2016/17, Wandsworth’s standard annual rate of emergency admissions to hospital for those ≥65 with dementia was 4,299 per 100,000 people, significantly higher than both London (4,052 per 100,000) and England (3,482 per 100,000) figures.